At immigration detention facilities, 'inspectors for hire' miss signs of neglect, say critics

When government inspectors made an unannounced visit last year to the privately run immigration detention center in Adelanto, Calif., they found inadequate medical and dental care, improper use of solitary confinement and perhaps more shockingly, braided bedsheets facility staff called “nooses” hanging from ceilings in detainee cells.

Two weeks after the Department of Homeland Security’s watchdog office issued a grim report based on that visit, another inspection took place. This one, however, was pre-announced and conducted by a company called the Nakamoto Group, which the Immigration and Customs Enforcement pays to inspect its detention facilities.

The Nakamoto Group, which wrote its own review of Adelanto, criticized the department inspector general’s findings as “erroneous and inflammatory.”

The inspector general “took a housekeeping problem and made it a suicide issue” in order to “sell their product” and get more attention for their report, Mark Saunders, a vice president of the Nakamoto Group, said in an interview with the Project on Government Oversight.

The spat between the Department of Homeland Security’s inspector general and the Nakamoto Group over Adelanto epitomizes the debate over oversight of the immigration detention system at a time when DHS is locking up a record number of people for violating immigration laws. At stake are the health and safety of over 50,000 people kept in detention on an average day.

There have been a long series of credible reports of medical neglect in Adelanto since it opened in 2011, including at least two cases where ICE’s own investigations uncovered evidence that inadequate medical care contributed to detainees’ deaths. In both 2017 and 2018, though, Nakamoto Group inspectors found that Adelanto complied with all federal detention standards, including those for medical care and suicide prevention.

In May 2018, a team from the inspector general’s office arrived at Adelanto unannounced. A report on their findings was published on Sept. 27, 2018.

Hanging bedsheets, which some Adelanto staff called “nooses,” were seen throughout their inspection.

“The contract guard escorting us during our visit removed the first noose found in a detainee cell, but stopped after realizing many cells we visited had nooses hanging from the vents. We also heard the guard telling some detainees to take the sheets down,” according to the inspector general report, which contained pictures of the hanging bedsheets.

This finding was prominently featured in many news stories on the inspector general report.

In their review of Adelanto conducted two weeks after the inspector general’s report was made public, the Nakamoto Group fired back at the inspector general, saying that it was misleading for the inspector general to call the bedsheets hanging in detainees’ cells “nooses,” since the sheets “were being used as privacy curtains or clotheslines” and there was “no evidence to suggest that any privacy curtain or clothesline” was used as a noose.

The inspector general report itself said that the bedsheets hanging in detainees’ cells were used as privacy screens and clotheslines — but also noted that staff and detainees called them “nooses” and that there was a history of bedsheets being used in suicide attempts. Osmar Epifanio Gonzalez-Gadba, a 32-year-old from Nicaragua, used bedsheets to hang himself in his cell in Adelanto in March 2017.

Nakamoto inspectors wrote that they observed no hanging bedsheets during their inspection, and that based on data provided by the GEO Group, Adelanto had experienced no “serious suicide attempts” in 2018.

However, according to a recently released investigation by the nonprofit Disability Rights California, it is “demonstrably false” that there were no suicide attempts at Adelanto in 2018. The organization, which under federal law has a right to inspect any institution that houses people with disabilities, wrote that during four days of visits to Adelanto last year, “we encountered several people who, as documented by Adelanto health care staff … attempted suicide between January 2018 and September 2018.”

In early 2018, Disability Rights California reported that a female detainee at Adelanto was found “in the shower in fetal position, fully dressed, and holding left bleeding wrist,” and was hospitalized for five days following what her medical records acknowledged as a suicide attempt. In August 2018, the report continued, “medical records describe a man experiencing auditory hallucinations and expressing plans to hang himself. A few days later, he attempted to strangle himself with clothing.” Again, clinical staff at Adelanto recorded the incident as a suicide attempt, but GEO Group did not record it as one because it did not result in “serious self-harm.” (GEO Group did not respond to an email asking for a comment on these allegations.)

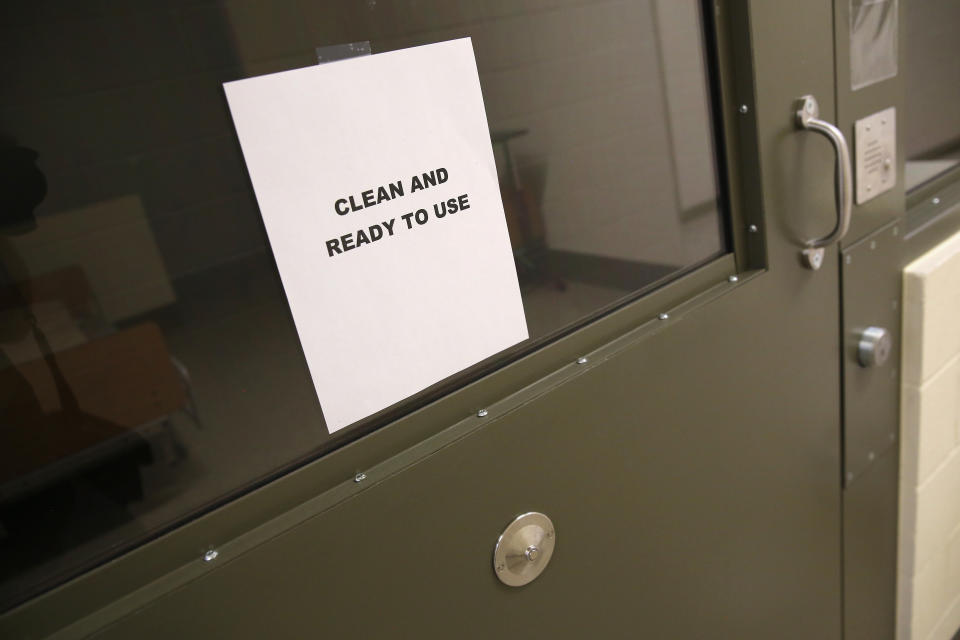

A former Adelanto detainee also cast doubt on Nakamoto’s finding that detainees were no longer hanging bedsheets in their cells. Alex Armando Villalobos Veliz, an asylum seeker from Honduras who was released from Adelanto on Jan. 31, 2019, said in a phone interview that detainees still routinely hung bedsheets for privacy, but GEO Group guards had told them to take them down and clean their cells the day before the Nakamoto inspection.

Villalobos was also instructed to do extra cleaning in the kitchen, where he worked. He said that the Nakamoto inspectors mainly interviewed GEO staff and English speaking detainees, and did not go into detainees’ cells in the section of the prison where he was held.

Nakamoto took issue with other parts of the inspector general’s report, including the inspector general’s finding that Adelanto did not provide any detainees with dental cleanings or fillings for a four-year period. Based on records that Nakamoto viewed, Saunders said, “they’d been doing them all along. ... We didn’t talk to detainees that had a single dental complaint,” he said.

In contrast, GEO Group’s written response to the inspector general’s report does acknowledge that there had been problems with medical and dental care, though the company said it had been resolved: “While we believe that a number of the [inspector general] findings lacked appropriate context or were based on incomplete information, we have already taken steps to remedy areas where our processes fell short of our commitment to high-quality care,” a GEO statement read.

The Nakamoto Group alleged that one of the most disturbing cases described in the inspector general’s report — that of a disabled detainee in segregation who “never left his wheelchair to sleep in a bed or brush his teeth” for nine days — was based on a misunderstanding. According to the Nakamoto inspection report, “[a] medical record review and interviews with staff and the detainee during this annual inspection revealed that the detainee is in fact not confined to a wheelchair, but was rather issued a wheelchair out of courtesy.”

Nakamoto wrote that the inspector general’s office should “use inspectors with detention and corrections backgrounds for future inspections to avoid … embarrassment to their office and ICE, especially since the inaccuracies have now been reported by the news media as fact.”

Tanya Aldridge, a spokesperson for the inspector general’s office, wrote in an email to POGO that “[w]hile we understand that the Nakamoto Group, along with ICE and facility staff, was critical of our report, we stand firmly behind the results of our inspection.” She declined to discuss Nakamoto’s allegations in detail, instead referring to a June 2018 inspector general’s report that found serious flaws in the contractor’s inspections.

“Nakamoto’s inspection practices are not consistently thorough,” are “significantly limited,” and “its inspections do not fully examine actual conditions or identify all compliance deficiencies,” the inspector general found.

Eleven senators led by Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., wrote to the Nakamoto Group last November to express concerns about the inspector general’s findings in both the June 2018 report on inspections and the unannounced inspection of Adelanto. Saunders said that Nakamoto had written to Congress refuting the June 2018 report, but he declined to provide a copy of the company’s response. Warren’s office also declined to release the response. A spokesman for her office said that “Senator Warren’s investigation of private immigration detention contractors CoreCivic and GEO Group, and auditor Nakamoto Group, regarding conditions at immigration detention facilities is ongoing.”

Scott Shuchart, who worked for eight years for the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Civil Rights and Civil Liberties, said that “Nakamoto is not wrong that the OIG lacks specialized expertise in detention,” and it was possible that the inspector general had gotten some details wrong in its report. But Shuchart said that “Nakamoto has no credibility because of the volume of problems it has failed to uncover at multiple facilities over multiple years. ... It is a checklist driven, superficial inspection process.”

Nakamoto Group vice president Saunders said the company regularly identified problems at facilities although “overall they may pass.” He thought Nakamoto, a small, minority-owned company with only 10 full-time employees based in Rockville, Md., was being unfairly grouped with “multimillion-dollar conglomerate companies” like GEO and CoreCivic. “Our president’s mother was born in a Japanese internment camp. ... That’s our historical profile,” he said.

The Nakamoto Group inspections publicly available on ICE’s website show that detention facilities do occasionally fail — most often, county jails that hold a small number of immigration detainees. Nakamoto gave a “deficient” rating to the Grand Forks County Correctional Facility, in Grand Forks, Neb., in May 2018. The Kandiyohi County Jail in Willmar, Minn., failed its ICE inspection in March 2018. (It passed a follow-up inspection six months later.)

The Nakamoto Group has rarely failed or even found serious violations at large detention centers like Adelanto, which has a capacity of up to 1,940 immigration detainees.

Nakamoto’s inspections of Stewart Detention Center in Lumpkin, Ga., found the facility was compliant with 39 out of 39 applicable detention standards in both May 2017 and May 2018. Stewart, like Adelanto, is run by a for-profit prison company, CoreCivic, which is GEO Group’s largest competitor. Like Adelanto, it is one of the largest immigration jails in America, with a capacity of nearly 2,000 beds.

Andrew Free represents the families of three detainees who died in Stewart since January 2017: Jean Carlo Jimenez Joseph, a 27-year-old who hanged himself in May 2017; Yulio Castro-Garrido, who was 33 years old when he died of pneumonia in January 2018; and Efrain De La Rosa, a 40-year-old Mexican national who committed suicide in July 2018.

Free noted the disturbing parallels between Jimenez’s suicide and De La Rosa’s. Both men had previously been diagnosed with schizophrenia, and suffered from hallucinations and suicidal thoughts while at Stewart. Both hanged themselves after spending weeks in solitary confinement. In both cases, a CoreCivic guard was fired for failing to perform a required check of the prisoner’s cell and then falsified logs to cover for that failure.

Amanda Gilchrist, a spokesman for CoreCivic, wrote in an email that she could not comment specifically on Jimenez’s and De La Rosa’s death other than to say that the company “has cooperated fully in the investigations by our government partners and law enforcement into these matters,” and that “the safety and well-being of the individuals entrusted to our care is our top priority.” She also noted that at the time of both deaths, “CoreCivic did not provide medical or mental health care services or staffing at Stewart Detention Center,” which were instead provided by ICE’s Health Service Corps.

Documents from Nakamoto’s inspection of Stewart in May 2018 note Jimenez’s death, but do not contain any mention of the guard’s firing for falsifying detention logs, nor does it analyze whether Jimenez’s extended stay in solitary confinement may have worsened his mental condition. It also does not discuss evidence that, in Free’s words, Stewart was “woefully understaffed,” as documented by the DHS inspector general in late 2017.

Free, the lawyer representing the detainees’ families, wrote in an email that he viewed Nakamoto’s certification that Stewart complied with all detention standards as a demonstration that the company’s inspections were a “whitewash” rather than “actual, independent reviews.”

Saunders, the Nakamoto executive, noted that the fact that a facility received an overall score of “acceptable,” or was found to be in compliance with a particular standard, did not mean that Nakamoto had found no problems. Each standard has multiple subparts, and inspectors go “line by line by line” through each of them in reports that are over 100 pages long, he said.

Critics say that the checklist approach is inherently flawed. The inspector general wrote that the checklist includes more than 650 subparts, which left Nakamoto employees without “enough time to see if the [facility] is actually implementing” its written policies. Tara Tidwell Cullen of the National Immigrant Justice Center, which has done extensive analysis of inspection data, said that “it’s very easy to gloss over conditions using only this checklist,” particularly since Nakamoto inspections are announced in advance. “If you give facilities a chance to clean up once a year for the inspectors, you’re not really getting an accurate view,” she said.

In December 2016, a Department of Homeland Security advisory group issued a report addressing ways to improve oversight of private immigration detention. It recommended that ICE revise its inspection methodology and potentially abandon or scale back use of Nakamoto, stating that “inspections should make greater use of qualitative review of outcomes, rather than simply using a quantitative checklist. The point of inspections is to provide meaningful evaluation of actual on-the-ground detention conditions in each facility.”

Even if a detention center fails a Nakamoto inspection, there may not be any consequences. Congress passed a law in 2009 requiring that ICE terminate the contract of any detention center that fails two consecutive inspections — but this has never happened since the legislation was passed. ICE treats Nakamoto’s inspection rating as a recommendation, which must be reviewed by ICE before it is made final. Saunders confirmed this in an interview saying, “everything we send to ICE is considered a draft … they have final approval.” He did not recall ICE ever changing inspectors’ conclusions.

But according to Tidwell Cullen, ICE may simply avoid issuing a final rating when its inspection contractors find that a facility is out of compliance. She wrote last year that based on her group’s analysis of data on ICE detention facilities from November 2017, four jails had received a recommended rating in their last inspection of “deficient,” “at-risk,” or “does not meet standards.” The final rating for all four of these facilities “had been pending for more than 100 days — by far the longest-pending inspections of more than 200 detention centers listed.”

Matthew Bourke, an ICE spokesman, wrote in an email that “ICE has a strong record of holding detention facilities accountable when deficiencies are identified.” Nonetheless, in response to the inspector general’s findings “the agency is currently re-evaluating the existing scope and methodology” for contract inspections, he wrote.

Advocates were pessimistic about the outcome of this review given ICE’s track record and the dramatic recent expansion of immigration detention. Tidwell Culllen said, “it’s not a problem that’s going away. It’s getting worse.”

Katherine Hawkins is an investigator for the Project on Government Oversight.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

Women divided by race over key issues, but with areas of overlap

Maverick Republican William Weld looks to run against Trump's 'malignant narcissism'

The Army's killer drones: How a secretive special ops unit decimated ISIS

The Soviets wanted to infiltrate the Reagan camp. So, the CIA recruited a businessman to bait them.