‘The Atlantic is definitely on fire’: Unusually hot ocean sparks up early hurricane season

The Atlantic Ocean is hot right now. Hotter than it’s supposed to be for this time of year, and hot enough to worry scientists — particularly ones who monitor hurricanes.

Those higher-than-normal temperatures help explain why the National Hurricane Center’s tracking map on Tuesday looked a lot more like a snapshot from August than June. It shows two brewing systems east of the Lesser Antilles, including one that has already reached tropical storm strength, Bret. Named storms in June are rare and past ones have typically popped in the Gulf of Mexico or near the Atlantic coast.

That hot water is the prime suspect for the early season activity, but not the only one.

“There’s no doubt it’s related to the extra heat down there,” said Jeff Berardelli, chief meteorologist for WFLA in Tampa Bay. “We typically wouldn’t have water temperatures that are above the critical thresholds across wide swaths of the tropical Atlantic this early in the season.”

Stronger Bret inches toward Caribbean islands. But some models predict it falling apart

Some spots in the Atlantic are so unseasonably hot, they’re now running at temperatures usually seen in September — which is three, long hot summer months ahead.

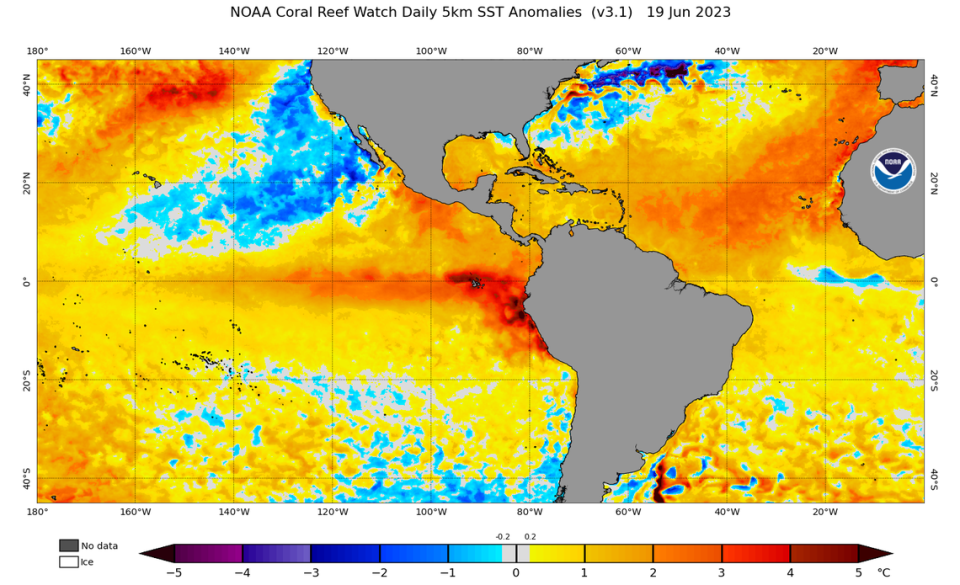

Ben Noll, a meteorologist with the National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research in New Zealand, tweeted a map showing those spots, which include large swaths of the main development region, where Atlantic hurricanes usually form from waves rolling off the coast of Africa.

This map highlights where current sea surface temperatures are warmer than they would typically be during *September*!

In other words, yellow areas indicate where the sea is as warm right now as it would normally* be in three months time!

It includes large swaths of the… pic.twitter.com/kkd0GS5SJG— Ben Noll (@BenNollWeather) June 17, 2023

On average, the tropical Atlantic is running about two degrees Celsius hotter than normal, or about 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit, according to NOAA satellite data. And it happened fast.

Michael Fischer, an assistant scientist with the University of Miami-NOAA Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies, said that between April to June, the region (including the eastern Caribbean) warmed about 1.6 degrees Celsius. In a normal year, he said, it warms about 1 degree in that same time.

“That’s greater than anything we’ve seen over the last 40 years,” he said. “The Atlantic is definitely on fire.”

Many spots have flashed past an important benchmark that usually doesn’t happen until later in the season — 26.5 degrees Celsius, the threshold scientists use to determine whether water is warm enough to support a tropical storm or hurricane.

The rate of rising sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in the tropical Atlantic Ocean these past three weeks is kind of mind-boggling. The dashed line indicates the 26.5°C isotherm, a value used as a reference threshold for whether water can support tropical cyclone development. pic.twitter.com/9qijBK37mW

— Dr. Kim Wood (@DrKimWood) June 15, 2023

Kim Wood, an associate professor of meteorology at Mississippi State University, called the rate of rising sea surface temperatures in the tropical Atlantic “mind-boggling.”

“We need a lot more than warm ocean water for [tropical cyclones] to form, and 26.5°C isn’t a hard-and-fast threshold, but seeing [sea surface temperatures] already exceed that value for so much of this region is... unusual, as many others have noted,” Wood tweeted.

And those pockets of abnormally hot water are already occupied. On Tuesday, the hurricane center was tracking both Tropical Storm Bret as well as another tropical wave close behind it. Hurricane models also had begun to hint at a third wave that could follow.

Why is it so hot?

The latest storm to form, Bret, is weird in several ways. For one, it’s way early.

Typically, the front half of hurricane season features storms that form in the Caribbean and spiral north. That flips around in late July or early August, when conditions line up for that infamous conveyor belt of tropical waves off Africa’s west coast. Some of those strengthen into tropical storms or hurricanes as they head west across the warming Atlantic.

Bret actually formed further to the east than any other early season named storm. Since 1850, only four previous storms have churned up east of the chain of Caribbean islands known as the Lesser Antilles in June.

Forecasters said the abnormally hot waters of the Atlantic could have definitely helped make that possible, but they aren’t the only factor.

“It’s a key ingredient but it’s not the only thing going on,” Fischer said.

It is just insane to me how a region this large has warmed this quickly. pic.twitter.com/TmgaupVYuZ

— Michael Fischer (@MikeFischerWx) June 8, 2023

Saharan Dust also tends to tamp down the tropics in the early summer. That cloud of loose dirt that floats off the west coast of Africa in the early summer typically slows or shuts down storm formation, blocking the sun and helping keep ocean waters cool. There’s less of that dust than usual this month.

There also are weaker than usual trade winds. Typically this time of year, a high-pressure system sits between Bermuda in the Azores, with a clockwise flow of air around it that helps cool the waters of the Atlantic.

“It’s fair to say the Atlantic has been unusually hospitable to tropical cyclone development this year,” Fischer said.

Uncertain season ahead

Despite the unseasonably hot waters, early forecasts from NOAA and others have called for a near-average hurricane season. That’s because of another massive weather phenomenon that is known to curtail storm activity — El Niño.

El Niño officially began earlier this month, and years with this weather pattern usually see fewer storms form in the Atlantic and more storm-shredding wind shear in the eastern Caribbean. That works directly against the storm-intensifying power of hotter oceans, leaving scientists with a lot of uncertainty about what this season may hold.

“We’re really in uncharted waters,” Fischer said.

And all of that is on top of the steadily building impact of climate change, which has already warmed tropical oceans by about 2 degrees Fahrenheit since the 1900s.

On Tuesday, NOAA noted that the ocean last month broke heat records, making it “virtually certain” that 2023 would end up in the top ten hottest years on record.

“This year shows us the potential of climate change,” Berardelli said. “When you take climate change and then on top of it you add natural factors that just happen to line up to create warm temperatures, you’re reaching extremes you’ve never reached in modern history.’