Attack of the mutants: how Britain plans to conquer the new Covid variants

Viruses, it turns out, have something in common with buses. You wait the best part of a year for a new variant to come along and then three or four turn up at once – each a little faster, fitter and stronger than those that went before.

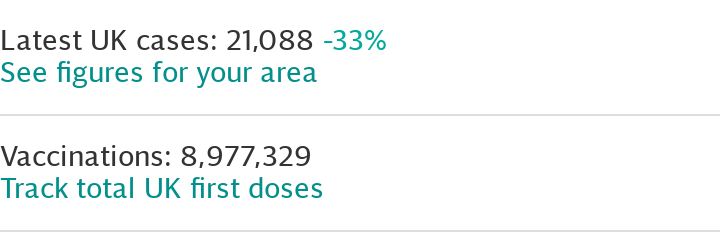

Such is the evolutionary advantage acquired by our own “UK variant” that it has been described as causing a “pandemic within a pandemic”. The chaos it has wreaked since first getting a grip in November was this weekend predicted to come to a crescendo in the capital, with medics facing their toughest 100 hours yet.

“For London, for critical care, I think it’ll be the next 100 hours that’ll count. That’s when the crescendo will play out – and this is when we need all our heroes,” tweeted Professor Geoff Bellingan, of critical care medicine at University College London on Friday in a bid to rally his troops. “Day shifts AND NIGHT shifts over this weekend and early next week. We’ve done this together so brilliantly so far...”

A third national lockdown and the extraordinary work of doctors like Prof Bellingan should see us through the current surge but the attack of the mutants is far from over. Even as new cases start to fall in Britain, other variants of SARS-CoV-2 with perhaps even greater potency are springing up across the world.

In South Africa, variant 501.V2 is already dominant in the Eastern and Western Cape provinces and is thought to be responsible for the country’s ferocious second wave. And in Brazil, a variant called P1 is causing terrible carnage.

Hospitals in the city of Manaus in the north of the country have once again reached breaking point, amid reports of severe oxygen shortages. This is despite up to three-quarters of the city’s population contracting Covid-19 last year.

"There is no oxygen and lots of people are dying. If anyone has any oxygen, please bring it to the clinic. There are so many people dying", a medical worker was filmed pleading in a widely shared video from the region last week.

Virologists are not sure why so many new variants of the virus are now – a year into the pandemic – on the march, but nor do they think it is a coincidence.

Mutations of the virus, it is suggested, are somehow converging. Each has sprung up independently in a different part of the world, but all share a remarkably similar constellation of genetic changes which confer a common advantage.

“After ~10 months of relative quiescence we've started to see some striking evolution of SARS-CoV-2 with a repeated evolutionary pattern in the SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern emerging from the UK, South Africa and Brazil”, wrote Trevor Bedford, a professor of epidemiology and genome sciences at the University of Washington, in a slightly terrifying Twitter thread last week.

Prof Bedford speculates that the pattern is explained by the virus coming under a common pressure to mutate. Specifically, he thinks that they may have emerged from hospitalised patients who have struggled a long time against the disease.

“My (highly speculative!) hypothesis is that the emergence of these variant viruses arises in cases of chronic infection during which the immune system places great pressure on the virus to escape immunity and the virus does so by getting really good at getting into cells,” he said.

“The fact that we've observed three variants of concern emerge since September suggests that there are likely more to come.”

Britain’s long-term strategic defence against Covid mutations and indeed future pandemic pathogens is being built today in a field in rural Oxfordshire.

From the outside, it looks like just another large industrial shed but when completed at the end of this year, the Vaccines Manufacturing and Innovation Centre (VMIC) at the Harwell Science and Innovation Campus, will have the capacity to make sufficient doses of nearly any vaccine for the entire country within months.

Matthew Duchars, chief executive of the VMIC, concedes that the project came too late to help with the first waves of Covid-19 – “that’s Murphy's Law, I guess” – but says it will be fully operational by December this year.

It will be capable of producing conventional vaccines as well as the new RNA jabs pioneered by Pfizer and Moderna. As such it should be well placed to see off any new variants of the virus that emerge to evade the protection provided by existing products, he says.

“We will be able to make 70 million doses [of vaccine] in a four-to-five month period,” he told The Telegraph. “The new Covid variants are absolutely part of the thinking. The VMIC is there to be able to fulfil that”.

Scientists around the world are already racing to work out if existing Covid vaccines will work against the known new variants. And the good news is most think that they will.

The variants identified in the UK, South Africa and Brazil, are all characterised by a series of small changes to the spike protein, the part of the virus that attaches to human cells. They seem to have made the virus more transmissible but do not appear significant enough to evade the antibodies produced by existing vaccines.

“If over 90 per cent of the protein remains unchanged, 90 per cent of the antibodies being produced would still be completely effective,” said Professor Beate Kampmann, director of the Vaccine Centre at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Data from Pfizer/BioNTech has shown promising signs that its jab will hold off the new variants, and British immunologist Professor Danny Altmann, at Imperial College London, has similar data of his own.

But this doesn’t mean we should rest on our laurels, said Prof Altmann: “There are new mutations all the time, but occasionally one will throw up a nasty variant. This will come back to bite us if we don’t address it.”

The Oxford AstraZeneca team are already working on new vaccines should they be needed.

“The University of Oxford and labs across the world are carefully assessing the impact of new variants on vaccine effectiveness, and starting the processes needed for rapid development of adjusted Covid-19 vaccines if these should be necessary”, an AstraZeneca spokesperson told The Telegraph.

BioNTech’s chief executive, Ugur Sahin, has previously said a tweaked vaccine could be developed in six weeks if needed.

The reason new RNA vaccines can be developed so quickly is because of the revolutionary new technology they use. Scientists essentially just adjust the code to match the changes in the spike protein in the lab and then use clones of that to manufacture a new batch.

It’s as if the enemy has a new sword, but the vaccine provides a new, specially adapted shield exactly designed to block it.

It is hoped regulators will be able to give the nod to tweaked vaccines more quickly, in the style of the annual flu jab which is adapted each year to tackle the most prevalent strain.

However, for flu there are “sentinel” labs across the globe dedicated to constantly tracking new strains of that virus. For SARS-CoV-2, in contrast, global surveillance is in its infancy and much more limited as a result.

Scientists say a “cat and mouse” game lies ahead, as vaccine producers scramble to keep up with the mutating virus. Unless we can up our surveillance game quickly and see the virus changing before it hits, it’s a game we are at risk of playing blind, say experts.

The new VMIC facility in Oxfordshire will provide Britain with better long-term defences when it comes on stream in 12 months’ time – most notably a large-scale domestic vaccine manufacturing capacity.

But until then the battle against the mutants will be fought largely with imported vaccines and crude non-pharmaceutical interventions, particularly social distancing.

In a best-case scenario, data will start to come in a few weeks showing all three of the current vaccines are effective at protecting the most vulnerable against severe Covid-19, including that caused by the new variants.

We may then also get a lull in transmission over the spring and summer months, reducing the chances of further, more serious mutations for a while at least.

Where things could yet go wrong is if it turns out that one or more of the existing vaccines don't work effectively, or if we don't reach enough of the most vulnerable in the current vaccination campaign before moving on to younger age groups.

The absolute nightmare, say scientists, is if a new vaccine-resistant variant emerges ahead of next winter and before the VMIC is built. If that happens the whole process may need to be started all over again.

Protect yourself and your family by learning more about Global Health Security

Do you have a question about what the new Covid variants will mean for vaccines? Send your queries to yourstory@telegraph.co.uk for our expert to answer in a video Q&A.