Attention Never Trumpers: Democrats Aren't Scared Anymore

I appreciated the Never Trumpers for their contributions to making life miserable for El Caudillo del Mar-a-Lago, since that's pretty much all they did. Their influence on the institutional Republican party has been that of a fart in a windstorm. (They did, of course, make the likes of Susan Collins and Ben Sasse feel Very Disturbed at the state of things before voting to give the president* pretty much anything he wanted.) But now there's an election coming and, alas, most of those people are still Republicans, and they still think like Republicans, and the Democratic Party should thank them for all their previous work aggravating the administration* and then tell them to take a seat in the back row until everything is over next year.

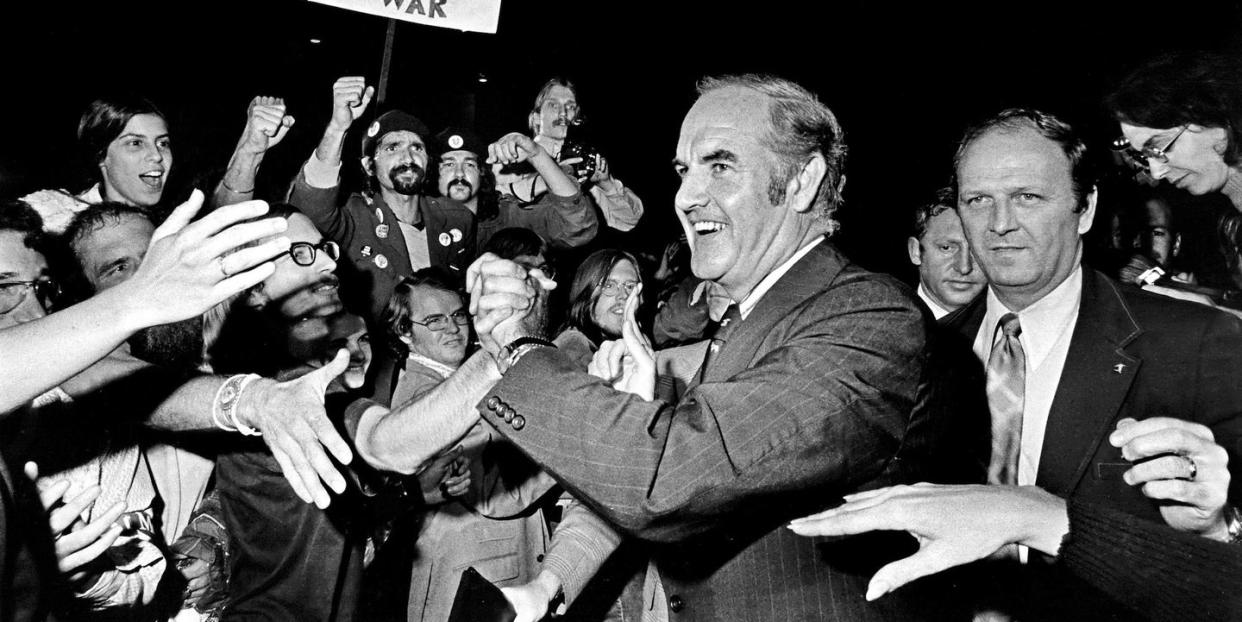

The latest train to come down this hackneyed track is from Charlie Sykes, the editor of something called The Bulwark—Motto: Kristol Needs Another Gig—in which he warns the Democratic Party not to nominate Zombie George McGovern this time around. In doing so, he tosses some history into the blender for Politico and comes up with slop.

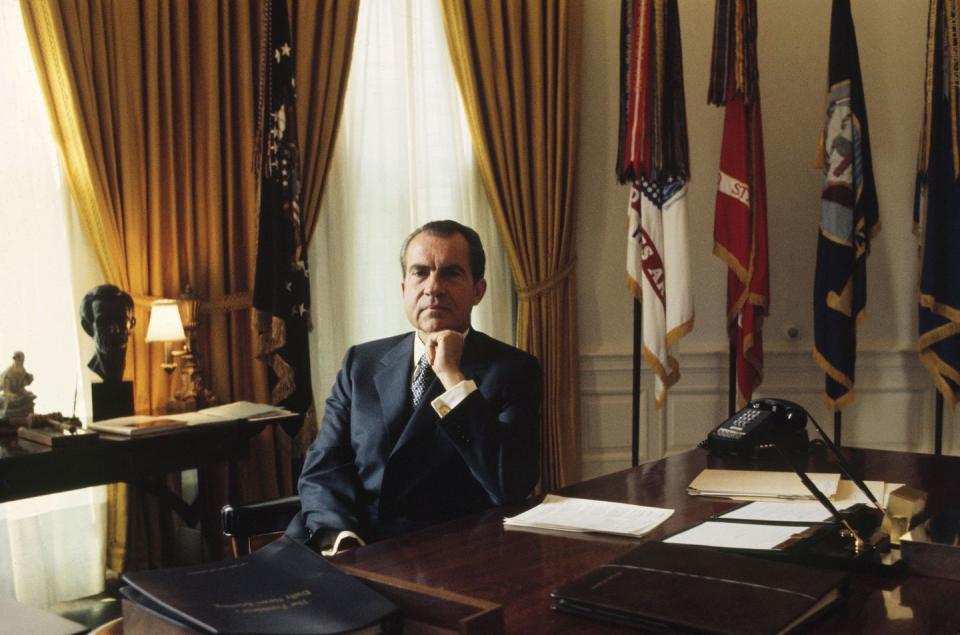

In the year leading up to it, the Democrats were giddy with anticipation. The country was still mired in a bloody war, the economy was a mess, and President Richard Nixon, while lacking Trump’s theatricality and instability, was regarded with fear and loathing by much of the country. In the 1970 midterms, Democrats won the popular vote in House races by 8.7 percent, while adding a dozen seats. In 1971, Nixon’s approval ratings dipped below 50 percent, and stayed there. Surely, they told themselves, they could beat this guy.

Nixon’s vulnerability attracted a host of potential challengers, with Senator Edmund Muskie, a previous vice-presidential candidate, as the front-runner. He had gravitas; The Times opined that “No national leader since Franklin Roosevelt has been better than Mr. Muskie in delivering a conventional ‘fireside chat.’” But they noted that despite Muskie’s appeal, many Democrats “believe the times call for radical change.” For some Democrats, Muskie “appears a little too cautious. He evokes respect, but not enthusiasm.”

And then:

This “mild dissatisfaction” gave an opening to a far more liberal candidate, one who spoke to the activated left of the party, George McGovern. For Democrats who shared McGovern’s anti-war passions, his record “establishes his moral superiority,” the Times wrote. But it also noted that others feared that “his views have too sharp a cutting edge and would energize as many elements as he won over.”

For the moment, let's put aside the fact that history has become fairly clear that the Muskie campaign was pretty thoroughly ratfcked by the Nixon White House. McGovern won the nomination because he ran a better campaign. Starting in Nebraska, what really was a Democratic establishment—hoping to revive the corpse of Hubert Humphrey's career one more time—set out to demolish McGovern before the convention. John Connally was soliciting big money for something called Democrats for Nixon. The AFL-CIO bailed on the campaign. (Thus, by the way, were born the "Reagan Democrats.") Nixon bought off the Teamsters, in part by commuting Jimmy Hoffa's jail sentence. A lot of this was ideological, but just as much was pure corruption. And then, of course, there was the ratfcking.

Now, we are prepared for Sykes to jump his motorcycle across the canyon.

That turned out to drastically underestimate McGovern’s weakness. As unpopular as he was, Nixon would go on to win 49 of 50 states, 520 electoral votes, and nearly 61 percent of the popular vote, beating McGovern by nearly 18 million votes. It’s possible that Nixon would have beaten any Democrat, but what happened in 1972 was not inevitable. It was, however, a choice. Democrats chose to move sharply left – to indulge their ideological id. Nixon ran against the party of “Acid, Amnesty, and Abortion.” The result was a massive landslide for a vulnerable incumbent.

In fact, McGovern was nothing more than a very run-of-the-mill prairie populist Democrat. Bobby Kennedy once called him the most decent man in the Senate. He was a war hero. His economic plan included a guaranteed annual income, which was something with which Nixon himself flirted. The move to the left, such as it was, was hardly sharp. As Sykes gets around to admitting, a lot of this sharp turn to the left was manufactured by the Nixon propaganda shop. And there was, of course, the ratfcking.

Moreover, you may have noticed that we moved from Nixon's poll numbers in 1971 to McGovern's "weakness." By May of 1972, Nixon was polling north of 60 percent, and he never dropped below 57 for the rest of the year. Much of this polling muscle came from Nixon's groundbreaking trip to China in February of 1972, and his Moscow summit in May that produced not only the ABM treaty, but also the first SALT arms-control agreement. That's a considerably parlay for an incumbent president, and the boost in the polls was hardly a surprise, and those numbers pretty much eviscerate Sykes's argument that Nixon was wounded going into that fall's election. As for Democratic "cockiness," he doesn't present a lick of evidence for that, and I certainly don't remember it that way.

The rest of the column is a fairly standard rundown of the perils of "going too far," mainly via quotes from some of the usual Democratic liberal hall monitors. But the real story here is the continued use of George McGovern as a Republican conjuring word. It was enough to scare two generations of Democratic politicians and policy makers. It's not going to work anymore. The most decent man in the Senate looks pretty good right now.

Respond to this post on the Esquire Politics Facebook page here.

('You Might Also Like',)