Audit shows cruel isolation policies, high levels of force prevalent in KY’s juvenile jails

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The Kentucky Department of Juvenile Justice has failed to comply with reforms called for in a 2017 critical inspection report, including better security and medical staffing, on-site mental health care and less use of solitary confinement for the teenagers in its custody, according to an independent audit released Wednesday.

As a result, despite years of outside scrutiny, the department’s eight juvenile detention centers continue to be mismanaged, with cruel isolation policies and high levels of extreme use of force, according to the audit.

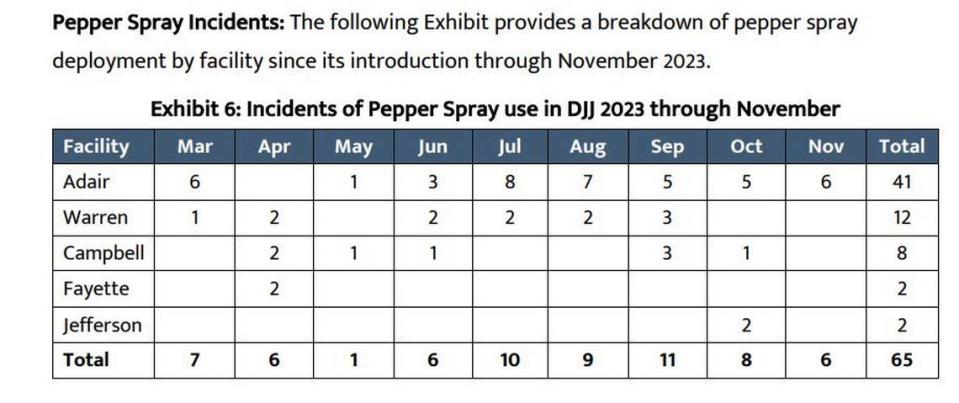

Under orders from Gov. Andy Beshear, the department last year equipped its security staff with pepper spray, but without providing a policy to clearly define when it should be used, according to the audit.

Staff in Kentucky’s juvenile detention centers have used pepper spray at a rate 73.9 times higher than in federal prisons that house adults, auditors wrote. At the Adair Regional Juvenile Detention Center in Columbia, staff used pepper spray at least 41 times over a nine-month period last year, they wrote.

The Herald-Leader reported last September that juvenile detention staff sometimes have misused pepper spray as punishment, even spraying it into cells where youths could not escape the burning chemicals or wash them off.

Just this week, a federal lawsuit alleged that a mentally ill 17-year-old girl spent much of the summer of 2022 locked — sometimes naked — in a filthy isolation cell in the juvenile detention center in Adair County, where security staff mocked her smell and ignored her cries for help.

Sign up for our Bluegrass Politics Newsletter

A must-read newsletter for political junkies across the Bluegrass State with reporting and analysis from the Lexington Herald-Leader. Never miss a story! Sign up for our Bluegrass Politics newsletter to connect with our reporting team and get behind-the-scenes insights, plus previews of the biggest stories.

“The state of the Department of Juvenile Justice has been a concern across the commonwealth and a legislative priority over the past several years,” state Auditor Allison Ball said in a prepared statement.

“The findings from this review demonstrate a lack of leadership from the Beshear administration, which has led to disorganization across facilities and, as a result, the unacceptably poor treatment of Kentucky youth,” Ball said.

The General Assembly last year instructed the auditor’s office to hire an outside firm to review the operations of Kentucky’s troubled juvenile detention centers. The $460,000 contract went to CGL Companies LLC of Lexington, a consulting firm for criminal-justice facilities.

“As a previous assistant Floyd County attorney who prosecuted juvenile delinquency cases, I am alarmed by the findings of this report, but I am hopeful this will provide clear direction for the numerous improvements needed within our juvenile justice system and open the door for accountability and action within DJJ,” Ball said.

Kentucky’s juvenile justice commissioner, Vicki Reed, resigned effective Jan. 1 after a long series of problems at her agency’s facilities, including neglect, excessive force, riots, assaults and escapes. Her immediate superior, Justice and Public Safety Secretary Kerry Harvey, also recently announced his departure.

A spokeswoman for the state Justice and Public Safety Cabinet, which oversees the Department of Juvenile Justice, said the agency was not given a chance to review the audit before its release Wednesday.

The department is making progress on its problems under Beshear, said spokeswoman Morgan Hall.

Salaries for security staff at the juvenile detention centers have been boosted to about $50,000 a year to help with hiring and retention, she said. As a result, facilities in Fayette, Boyd and Breathitt counties are close to full staffing levels, she said.

Beshear ordered boys and girls housed in separate facilities to avoid further problems like the rape of a teen girl that occurred during a 2022 riot at the Adair Regional Juvenile Detention Center. He equipped security staff with defensive equipment, such as tasers and pepper spray, and he hired a former state prison warden as director of security, she said.

“Unlike the previous administration, we’ve started making sweeping improvements to the juvenile justice system, including making it a priority to protect staff and juveniles and create secure facilities by increasing staffing levels,” Hall said.

Calls for reform ignored

In 2017, the nonprofit Center for Children’s Law and Policy of Washington, D.C., sharply criticized the Kentucky Department of Juvenile Justice in a report citing a near-total absence of mental health care in the detention centers; chronic staff shortages and inadequate employee training; a lack of special education for youths with learning disabilities; and few opportunities for residents to file grievances that could reveal abuses.

The report saved its strongest criticism for the controversial practice known as “room confinement” — leaving youths with little supervision in small concrete isolation cells as punishment for misbehavior.

State officials under former Gov. Matt Bevin agreed to spend $130,000 on that investigative report after a tragedy.

In 2016, 16-year-old Gynnya McMillen died from a heart condition while being ignored in room confinement at the Lincoln Village Regional Juvenile Detention Center in Hardin County, now closed. Her death went undiscovered for more than 10 hours. An investigation showed that detention center staff falsified logs to make it appear they were checking on the girl’s safety throughout the night.

However, few of the problems uncovered in 2017 have been fixed, auditors for CGL Companies wrote in their new report.

If anything, the juvenile detention centers face a fresh round of problems, they wrote.

The COVID-19 pandemic wreaked havoc on the facilities, first draining their populations and then, as the virus began to subside, quickly refilling them. More than 3,000 youths entered the juvenile detention centers in Fiscal Year 2022, up from about 1,800 the previous year.

Also, the national shortage of corrections officers has hit the youth facilities just as hard as it has local jails and state prisons. Constant staff shortages and mandatory overtime make it impossible to improve operations, auditors wrote.

“Our review found little if any of the findings from the 2017 report issued by the Center for Children’s Law and Policy have been corrected in DJJ facilities,” auditors wrote.

“Findings regarding the overuse of isolation and room confinement, the use of a punishment based behavior management system, the poor quality of their policy manual, and specific medical and mental health findings have not been addressed,” they wrote.

On isolation, for example, the Department of Juvenile Justice has no clear set of policies for when it’s appropriate, and it even uses different terms for the practice, such as “room restriction” and “room confinement,” auditors wrote. But whatever it’s called, it involves locking youths alone in a room behind a closed door for a period of time, and in Kentucky’s juvenile detention centers, officials misuse it, they wrote.

Because it threatens their mental health, isolation of youths should only be used briefly and in specific instances, such as when a youth poses an immediate safety risk to himself or others, the auditors wrote.

However, isolation is much more widespread in Kentucky’s juvenile detention centers, they wrote.

“Isolation is utilized in Kentucky DJJ inconsistently,” they wrote. “Site visits revealed isolation used for disciplinary, non-behavioral and housing assignment purposes.”

Less isolation, more health care

The auditors recommended that isolation at the juvenile detention centers be limited to cases involving immediate safety threats, suicide risks or a need for medical seclusion, such as an infectious disease.

On the use of force by staff, the auditors recommended that tasers be removed from the facilities and that pepper spray be limited to trained supervisory staff only, with a goal of removing pepper spray if staffing levels improve and security staff can regain control and prevent more violent outbursts.

The auditors also recommended that physical and mental health care is made more available inside the juvenile detention centers. At present, youths are discouraged from requesting medical attention, assuming there is even a health care professional available to them, auditors wrote.

Salaries at the juvenile detention centers are so low that they’re constantly struggling to find medical staff, they wrote. For example, the starting salary for a registered nurse at one of the facilities is $56,388, which is far below what nurses can command in other jobs, they wrote.

Nor does the Department of Juvenile Justice provide adequate mental health care to the youths in its custody, auditors wrote. Licensed professionals with graduate degrees should be hired to work on site, they wrote.

“Many juveniles entering the system have experienced trauma, abuse or neglect, which can significantly impact their mental well-being. Juveniles within detention facilities often exhibit behavioral and emotional challenges that require specialized attention,” they wrote.

“Our observations left us with the perception that there is not a comprehensive approach nor sufficient licensed staff to address the significant mental health complexities inherent in this population,” they wrote.

“Mental health professionals are needed to conduct comprehensive assessments to identify any underlying mental health disorders, such as depression, anxiety or conduct disorders. In addition, they are instrumental in crisis intervention and determining the self-harm risk level of the youth.”

Also, the auditors said the Department of Juvenile Justice failed to provide adequate education for youths in its custody despite having classrooms and an agreement with local school districts to offer teaching services.

There often is no instruction in classrooms, auditors wrote. Instead, youths might be given projects to work on in their housing units, sometimes with little or no oversight. Teachers might or might not visit the facility.

At the Warren Regional Juvenile Detention Center in Bowling Green, “we entered a classroom on a Thursday, only to find that the students were watching a movie (The Blind Side) under the supervision of a correctional officer. The three educators were in a separate room with no youth,” auditors wrote.

“Also at Warren, all the youth interviewed freely volunteered that every Friday is ‘movie day’ in education, where no instruction occurs.”

Lawsuit: Mentally ill teen girl abused in filthy cell at KY juvenile detention center

State lawyers: KY juvenile detention center keeps youths in lockdown too much