Aurora St. Luke's hospital a national leader in using implant to monitor heart failure, give patients added freedom

Last summer, eight years after being diagnosed with heart failure, 76-year-old Mary Korte was on vacation, hiking at about an 8,700-foot elevation in Ruidoso, New Mexico.

Korte was having a hard time breathing and felt extremely tired. Something was off.

Almost 1,400 miles away, in the cardiology department at Milwaukee's Aurora St. Luke's Medical Center, Korte's nurse knew the same thing. Something was off.

In January 2020, Korte had a small sensor implanted into her pulmonary artery, which carries oxygen-depleted blood from the heart to the lungs. The sensor measures the amount of pressure in that artery, looking for early indications of worsening heart failure.

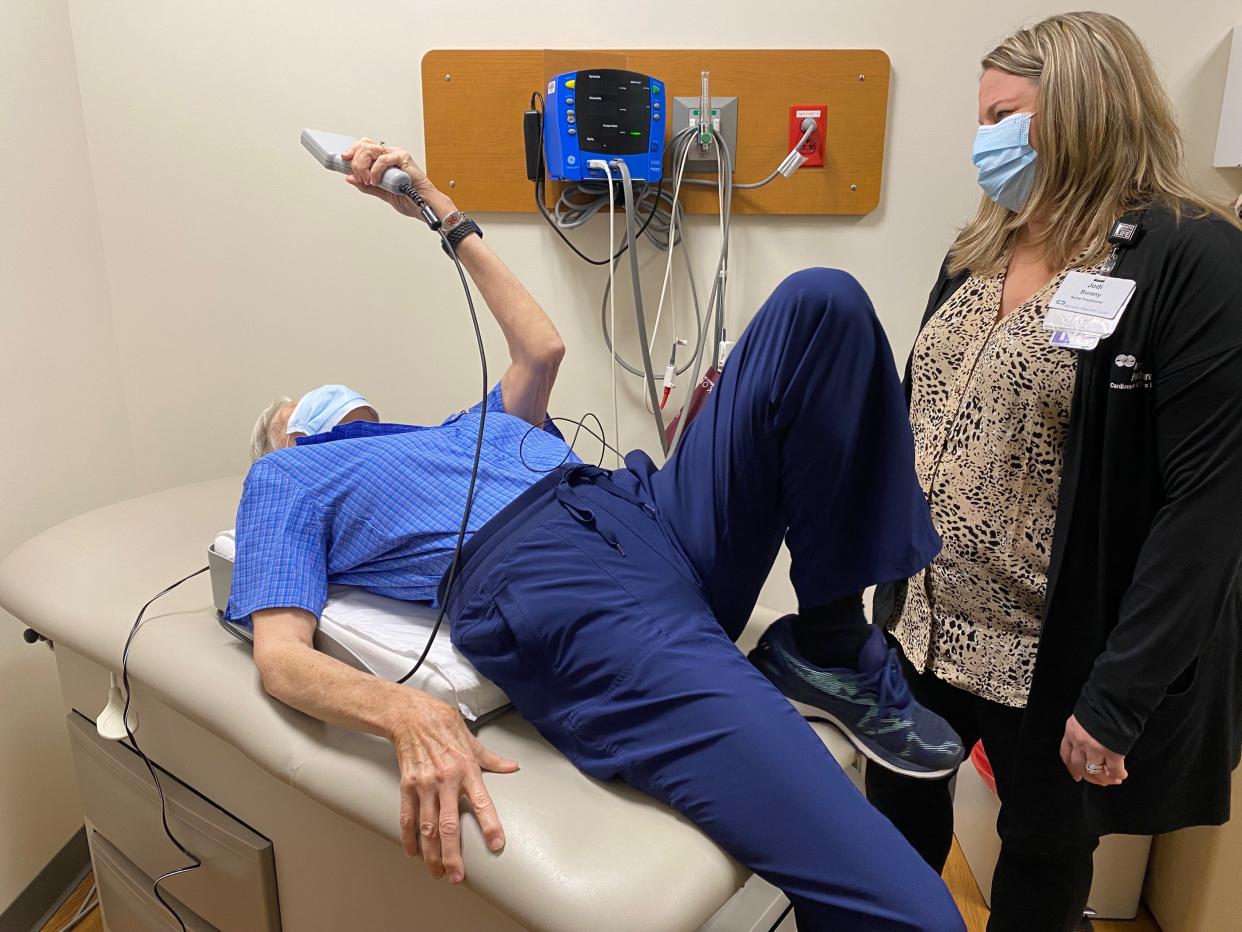

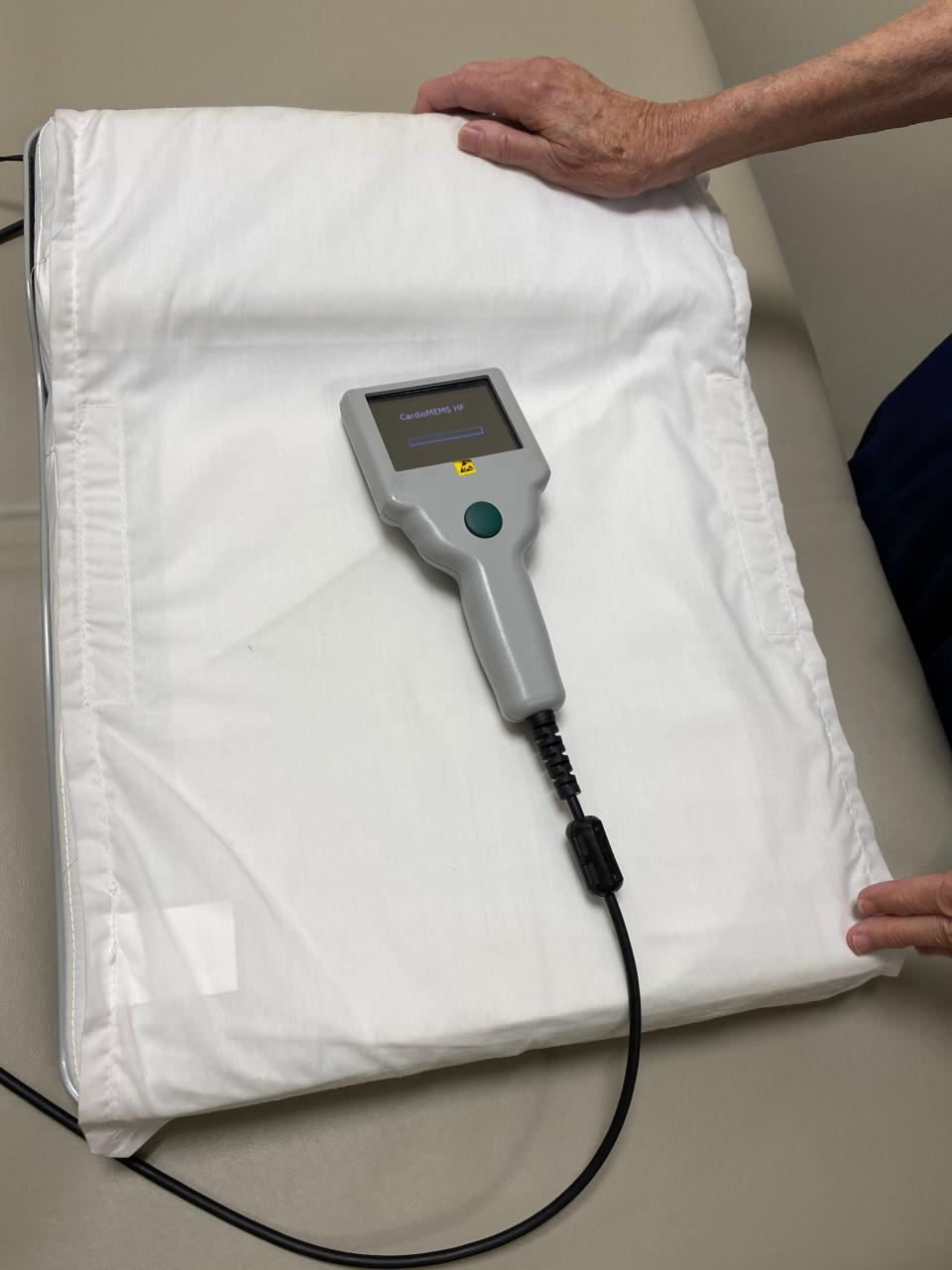

On that morning, when Korte laid back on a pillow that beams data to her medical team in Milwaukee, the numbers the nurse saw looked concerning. She called her patient up to ask if she'd been doing anything different.

Korte seemed to be retaining fluid more, the nurse said, a dangerous situation for heart failure patients.

Would being at an 8,700-foot elevation have anything to do with it, Korte asked. Absolutely, her nurse replied.

"I thought, OK, well now there's a reason," Korte said. "I'm not being a wimp!"

The call from her nurse stopped her from going any higher. Korte also knew what to do until she could get back down to a lower elevation: increase her diuretic medication, which makes her body produce more urine and, as a result, combats excess fluid retention.

Most reassuring, Korte didn't reach the point of having to be hospitalized while in New Mexico.

The medical device that Korte had threaded into her pulmonary artery in 2020 is called CardioMEMS and was developed by Abbott. It was first approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2014, and again for expanded use for people who are in earlier stages of heart failure earlier this year.

The Advocate Aurora Health System has implanted more of the devices than any other health system in the world: 1,000 across all of its hospitals. And Aurora St. Luke's Medical Center in Milwaukee has established itself at the fifth highest-volume hospital for the devices nationwide, having completed around 350 implants.

Advocate Aurora Research Institute conducted two major studies on the technology that led to the device's approval by the FDA.

The goal of using the device is to keep patients with chronic heart failure out of the hospital. Advocate Aurora has seen a 50% reduction in the number of hospitalizations among patients who have the implant, according to data provided by the health system.

But there is also a major secondary benefit, said Dr. Nasir Sulemanjee, Korte's cardiologist and medical director of the advanced heart failure and transplant program at Aurora St. Luke's. Having the device empowers patients to take charge of their condition and learn more about what managing heart failure looks like for them.

Left untreated, the average life expectancy for a heart failure patient is five years. New medications have improved outcomes for many, the doctor said.

"Unfortunately, the majority of the patients still don't get the right treatment for heart failure, and we still see very high rates of mortality in patients with heart failure," Sulemanjee said. "Five years, almost 50% of the patients don't make it."

Education and empowerment

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 6.2 million American adults have heart failure.

Despite the sense of immediacy that comes from its name, heart failure is considered a chronic condition. Patients live longer when given access to medical care and drugs, and when they adopt certain lifestyle changes that help manage the condition, including lowering sodium consumption and increasing physical activity.

Education around the condition is particularly important, for patients and for society as a whole.

The CDC estimates that in 2012, the nation spent $30.7 billion on treating heart failure, including costs of health services, medications and missed days of work. In 2018, 13.4% of death certificates mentioned heart failure.

Korte, an avid traveler and former professor in Concordia University Wisconsin's science department, got her diagnosis in 2013. She had visited her primary care doctor before leaving for a trip to San Antonio. He had run some tests, and when the results came in, he called her on vacation and told her to immediately pick up medication at a San Antonio pharmacy, and then come in to see him when she got back home.

Korte approached her diagnosis with a sense of resolve and a desire to do everything she could to manage her condition.

She became an avid label reader of grocery store foods, carefully watching her sodium intake. She started cooking with more fresh vegetables and ate more vegetarian meals. She had always been physically active, and made sure to remain so.

But getting the implant gave her an even more intimate understanding of her disease and gave her the chance to essentially be part of her own medical team.

The team at St. Luke's taught her how to take the readings, something she does every morning after waking up, along with weighing herself (weight gain with swelling in the feet, legs, ankles, or stomach is a symptom of heart failure). The monitoring is just part of her daily routine, she said.

She's even learned how certain foods can influence her condition. Cheese, which can have high sodium even though it doesn't seem salty, was one surprise food she now limits.

Doctors have to appreciate these individual differences in patients' diets and lifestyles while treating them, Sulemanjee said.

"It allowed us to manage Mary in a more educated and personalized fashion for her," Sulemanjee said. "We wanted her to live her life and we obviously wanted her to do what she wanted to do."

Increasingly, Korte will know exactly why and when to expect a call from her nurse. When when she eats sushi, for example, she answers her nurse's call and discloses that right away. Her nurse tells her to adjust her medications and keep living her life.

"You learn your limits," Korte said. "So if I have one dragon roll, I'm OK, but if I just stuff myself and stuff myself and stuff myself, that's too much. And I don't have the miso soup anymore."

She hasn't been admitted to the hospital once since getting the implant.

A renewed peace of mind

The procedure to get the CardioMEMS implant takes about 30 to 45 minutes, and is done by surgeons going through either a vein in a patient's groin or neck to reach the pulmonary artery.

Surgeons measure the size and structural quality of the artery before making an implant. Preparation for the surgery takes about an hour, and doctors ask the patient to stay for another hour or two before sending them home.

The medical team also takes time to train the patient on how to use the device, checking in with patients in the first week to make sure they're getting a hang of things.

There are some challenges that come with the expanded use of these devices, Sulemanjee said.

On the patient side, it's very important that people are empowered to follow through and make sure that they are taking readings every day. For some patients, even though most insurances cover the device, upfront costs can also create a barrier. Some insurance providers have "dragged their feet" on covering the device, Sulemanjee said, though that has greatly improved in recent years, especially since Medicare started covering it.

Another challenge is that of scale: St. Luke's started the program with just one nurse, but has since added one more nurse and two nurse practitioners to help read results and keep in touch with patients. The hospital will need to keep growing those resources, the surgeon said.

"I think we've demonstrated the utility of this without any doubt," Sulemanjee said. "And I think that's why it's easy for us to now ask for more resources if needed."

Also key to expanding access to the technology is making sure that other cardiologists can see the power of the device. Sulemanjee said many clinicians feel the device is "unnecessary or not needed."

Some have raised questions about just how much the device helps patients after a study published in the Lancet journal found a slight, but not statistically significant, benefit from the implant. However, further analysis showed that the pandemic changed people's behavior, from fewer people going to the hospital because of COVID-19 fears to people just eating out less.

As a result, Sulemanjee said, both patients with the device and those without it saw lower hospitalization rates. However, an analysis done before the pandemic found the implants could be significantly beneficial.

For the doctor, who even has relatives of his own using the implant, those benefits are clear. He recalled a patient from Kenosha who, before getting the implant, had to be hospitalized while on vacation in Tennessee. His kids told him not to risk traveling again.

He was allowed to book another vacation to the Smoky Mountains right after he got his implant, finally able to get back to his family's annual tradition of going there. That's the type of peace of mind the device can bring to patients, their families and their doctors, both Sulemanjee and Korte said.

"And it makes you feel safe living your life," Korte said. "I mean nobody is 100% guaranteed of anything. But you know, as a patient, that people are caring for you on a daily basis, and monitoring the situation."

Contact Devi Shastri at 414-224-2193 or DAShastri@jrn.com. Follow her on Twitter at @DeviShastri.

THANK YOU: Subscribers' support makes this work possible. Help us share the knowledge by buying a gift subscription.

DOWNLOAD THE APP: Get the latest news, sports and more

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Aurora St. Luke's becomes a national leader for heart failure implant