Austin musician Casey McPherson opens Everlum Bio lab to treat, find cure for daughter Rose

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Rose McPherson has an infectious laugh. She heads to the front door of her Northwest Austin house and tries the knob to see if she can open the door.

"Are you trying to escape?" her father, Casey McPherson, asks. She giggles, flashes a mischievous grin and runs to the other side of the house.

Rose, 7, communicates with giggles, screeches and sometimes screams. She is trapped inside her body by a genetic mutation, HNRNPH2, that progressively has stolen her ability to communicate.

She went from saying "Mommy" and "Daddy" at a year old to losing that ability at 18 months old.

Now Casey McPherson, best known as an Austin musician and frontman for Alpha Rev and Flying Colors, has started a nonprofit foundation, To Cure a Rose, to raise money for a treatment for Rose and a laboratory, Everlum Bio, to help families like his create personalized treatments for kids with rare diseases.

Getting Rose's diagnosis

Rose's parents, McCall and Casey McPherson, noticed how little she moved in the womb. When she was born, she wasn't breathing but was revived quickly. "All throughout this process, we were told, 'This is normal. Not every baby is born the same,'" Casey McPherson said.

She would choke on food or fall face-first without extending her arms to brace herself while trying to walk.

The stress of a child with a disease took a toll on the family. Rose's parents divorced, but remain united in her care. Rose also has a sister, Weston, now 9.

When Rose stopped speaking, her parents pressed for a genome sequence instead of an initial genetics panel. Four years ago, they got the results. Doctors recited a string of characters, HNRNPH2, with no cure.

"I had no idea what I was looking at," Casey McPherson said. "I fell asleep in biology class."

Rose continued to lose abilities. "She used to sing with me," McPherson said. "That's gone away."

Seeing hope in other rare diseases

In recent years, there has been some progress in treating rare diseases by using new technology, like antisense oligonucleotides or ASOs, which can modify the way a gene expresses itself; small molecule inhibitors, which block the way a protein functions; and gene therapy, which replaces a bad copy of a gene with a good copy. These treatments have been used in adults for targeted cancer therapies.

In childhood rare diseases, breakthroughs have happened this decade.

Spinal muscular atrophy now has a gene therapy treatment, given shortly after birth to introduce a new copy of the SMN1 gene. Babies now born with SMA are identified at birth and treated within a month.

This year, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the first gene therapy for Duchenne, a form of muscular dystrophy. Similar treatments are in the pipeline for Angelman syndrome, a rare disease that causes developmental delays.

As McPherson gathered information about Rose's disease, he met other families of kids with rare diseases, including Julia Vitarello, whose daughter Mila was diagnosed with Batten disease, a fatal neuromuscular disease. The mom from Colorado saw her very typical child lose abilities starting at age 3.

Vitarello started a foundation in 2016 and worked with doctors at Boston Children's Hospital. Within a year, they developed a treatment for Mila, naming the medication Milasen. After FDA approval for a clinical trial, Mila stopped having seizures the first year of having Milasen, Vitarello said. But the victory was short-lived. Mila died in 2021 at age 10.

"I don't know how any parent ever deals with this," Vitarello said of Mila's death. "There is a silent pandemic of children with rare diseases."

McPherson said he learned from Vitarello's journey and became inspired. She continues to advise him, and they are now dating.

More: Baby Elias is first child in Texas to receive partial heart transplant at Dell Children's

The problem with rare diseases

A genetic mutation disease like HNRNPH2, estimated at about 150 cases globally, lacks enough patients to make finding a cure profitable for pharmaceutical companies or to do extensive clinical trials if a treatment is discovered.

Rare disease foundations have raised money to develop drugs that are shelved. The question then remains for families and foundations, "Who owns the drug?"

Starting a lab for Rose and others

McPherson didn't want Rose's treatment to get shelved: "I need to start a lab where family foundations could do drug development work and own everything."

He began Everlum Bio, a for-profit company with a $1.5 million investment from Austin entrepreneur Rick Barkley.

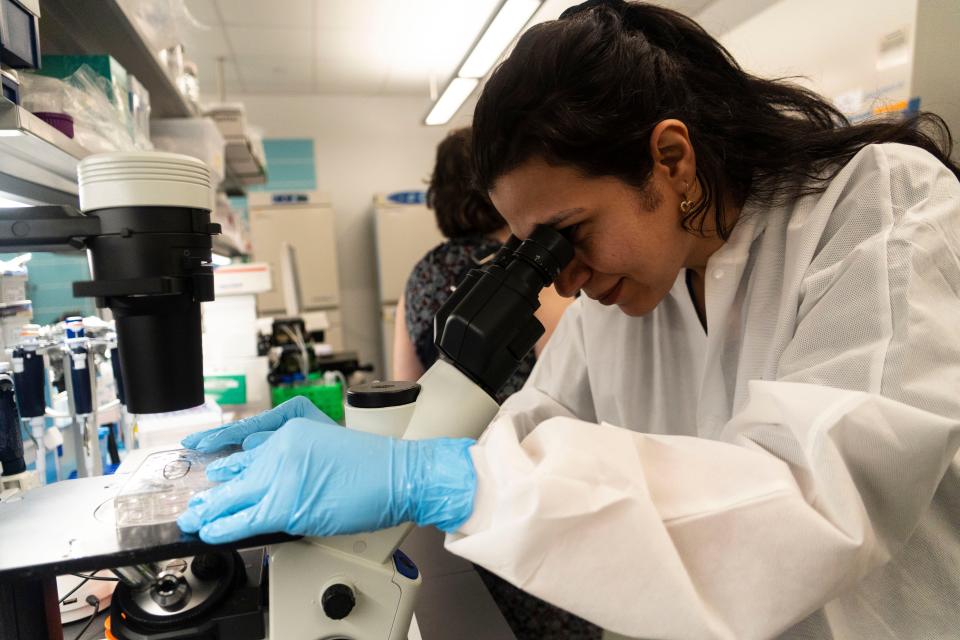

Everlum Bio is based at Austin Community College's bioscience incubator, which houses startups. The college provides the equipment and charges rent for the space.

"They've saved us millions of dollars," McPherson said. "I probably couldn't have started Everlum without them."

If a treatment found at Everlum is successful and approved by the FDA, the families will own the treatments to help their child and others. Insurance to pay for treatment would be in play after FDA approval of a treatment.

McPherson said any revenue generated by a successful treatment for Rose would be reinvested into To Cure A Rose Foundation to help other H2 kids.

Four years ago, McPherson met Rodney Bowling, a father himself, who worked in medical research in antibody discovery and DNA. Bowling is now chief science officer for Everlum Bio and working to create a treatment for Rose and eight other children with different genetic diseases.

Bowling explains a treatment this way: Rose and kids like her are like baking a cake without any eggs. Once the cake is made, you just can't put the eggs back in there. What can you do to fix that baked cake?

He's working on a treatment, while maybe too late for Rose, might help the next generation of Roses.

"My first hope is that we can stop the loss and how much better would it be that we can actually give her back that function?" Bowling said. "That would be wonderfully amazing."

Jackie Skinner-Foster's son Harvey, 3, is one of those children whose cells are being studied by Everlum Bio. Harvey's DLG4 mutation causes seizures and neurological delays, which affects about 45 children.

She said Harvey doesn't walk or crawl; he can't feed himself or communicate.

She said she vetted a lot of labs including the Boston Children's lab where Milasen was made.

"Almost nobody out there was doing what they are doing," Skinner-Foster said of Everlum Bio. "We didn't have millions of dollars to pay your average researcher to do this work."

Everlum Bio hopes to make the preclinical work a $100,000 to $200,000 process. If the lab is successful, the cost to family foundations will continue to fall because obtaining FDA clearance might be easier if Everlum Bio consistently proves the science works.

"This is our only shot to create a treatment for our son," Skinner-Foster said. "If this model pans out and is financially doable, our hope is to fund other treatments."

More: How this Texas boy could help change stroke protocols at Dell Children's and beyond

Into the lab

In Rose's case, Bowling and his team at the incubator have been able to grow Rose's neural cells using a blood sample from Rose. Her neural cells look different than normal brain cells. Instead of having cells that have big connections with other cells, Rose's cells are all clumped together lacking many connections.

Everlum Bio has found seven ASOs Bowling believes can work for Rose. Mice created at Jackson Laboratories in Maine have been given Rose's condition to test the chosen ASO to see if there is an improvement.

If that works and tests can escalate successfully, Everlum Bio can request from the FDA a clinical trial for Rose to give her the ASO treatment intravenously in the spinal column. McPherson estimates, depending on how much the FDA requires, the foundation might need as much as $5 million to get to a phase one trial to inject the drug.

"If I think about it too hard, I get overwhelmed and really depressed," he said.

Addressing the money problem

The process is expensive and takes time. For now, Rose's treatment is on hold while To Cure a Rose raises more money. McPherson said he has raised $800,000, which has gone toward growing Rose's cells in the lab, finding the ASOs and growing and testing the mice.

To Cure a Rose foundation is trying to raise separately $1.8 million by the end of 2023 for safety studies, and an additional $3 million by the end of 2024.

Getting the treatment into Rose

Developing the treatment is the first hurdle. For a clinical trial, McPherson will need a doctor to lead the trial to inject Rose.

McPherson has been consulting with Dr. Leah Harris, who chairs both the department of pediatrics at Dell Medical School and the Dell Pediatric Research Institute. She recently served as the interim president of Dell Children's.

Once the FDA has given approval for the clinical trial for Rose, Harris said she will bring it to the hospital's institutional review board for approval. Dell Children's has done clinical trials for other children with rare diseases.

Building personalized treatments quickly based on genetics is the future of rare diseases, Harris said.

That is happening every day in cancer treatments for adults, who now have treatments based on the genetics of their tumor, Harris said: "We are tailoring therapy based on genomics."

Harris has placed geneticists across departments at Dell Children's such as neurology, cardiology, oncology and fetal medicine to understand how genetics impact a child's disease and how to target treatment.

Back at home with Rose

Casey McPherson sees the frustration in Rose's eyes, in her screams. "It's like my child is trapped," he said.

He uses music to calm her, swings her around and around until she giggles. He worries what will happen when Rose hits puberty. Will it be too late for her? Will she become catatonic? He said they have to hope.

"I just want Rose to be able to say 'Daddy' again," he said.

Rose Fest

Benefiting To Cure a Rose Foundation, featuring Alpha Rev, Broken Arrow and Cory Morrow.

6 p.m. Saturday

Buck's Backyard, 1750 FM 1626, Buda

$35 admission

Tickets and information: betterunite.com/rosefest

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Austin musician Casey McPherson opens lab to treat rare diseases