Aviation school at Jacksonville University turns 40 amid pilot shortage at airlines

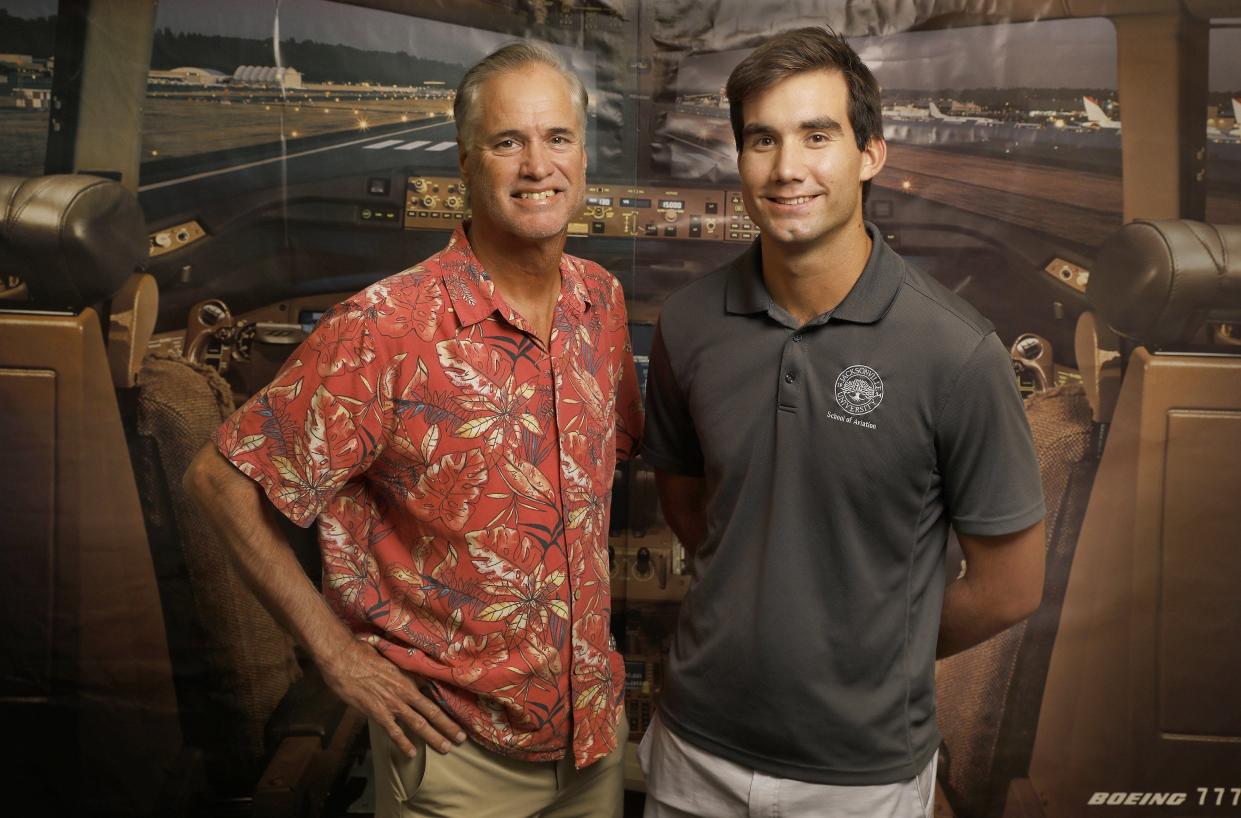

Before an interview at Jacksonville University, Mark Stiehl, graduate number one in the school's 40-year-old aviation program for undergrads, briefly doubted his decision to wear a flowered Hawaiian-style shirt that afternoon. He hadn't been expecting a photographer to show up.

But what the heck, he figured: He's retired, happily, after a long, lucrative and globetrotting career as a pilot for FedEx, and he's frequently turning down offers to return to the cockpit in an industry that needs more pilots.

Flying was great, really great, he said. But these days he'd rather be fishing. So the shirt is just fine.

Stiehl entered JU's School of Aviation in its first year, 1983, already possessing a four-year degree from Florida State, which gave him a head start on other students.

In 1985 he was the fledgling program's first and only graduate.

Since then, 857 other people have graduated from the aviation school: 512 on a track that leads to becoming a pilot, and 345 on a track that leads to other positions in the industry, said Matt Tuohy, a retired Navy pilot and director of the School of Aviation.

The school said this year there were 108 new students, double the year before — growth caused, at least in part, by a much-publicized need for new pilots and managers in the industry, which still hasn't recovered from layoffs and retirements during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The flow-through now is insane,” said Stiehl, 63. “It’s like they’re sucking pilots up, when back then you had to climb through the ranks.”

That's something most definitely on the mind of his nephew, Rhett Stiehl, 22, a current student in the program who has already accumulated 170 hours of flying time and several piloting licenses.

He went to Massachusetts Maritime Academy his freshman year, where he had an eye on becoming a sea captain. But then his uncle, and his FedEx plane, landed in Tampa, where Rhett grew up. That gave him a chance to sit in the cockpit and run through the pre-flight routines. His plans changed quickly.

He enrolled in JU and its flight school, just as his uncle had almost 40 years ago.

"The future is bright for him, compared to when I did it," Mark Stiehl said.

A shortage of airplane pilots had been building for several years but was made worse during the pandemic as air travel collapsed and airlines encouraged pilots to take early retirement, The Associated Press noted. Travel has rebounded, but a lack of pilots, especially at smaller regional airlines, has led to numerous canceled or delayed flights.

The government estimates that there will be about 18,000 openings per year for airline and commercial pilots this decade, with many of those replacing pilots who reach 65, the federal mandatory retirement age.

Asked where he sees himself in five or 10 years, Rhett Stiehl said he's aiming for FedEx too, or one of the major passenger lines, “Flying, at least right [co-pilot] seat," he said. "I still have to get there. I still have to put in the work.”

Given the pilot shortage, that's a strong possibility, said Tuohy, though nothing is handed to anyone. “The opportunity’s easier, but the work required to get there is the same, or harder," he said.

'You get to fly'

Mark Stiehl, who grew up, as he says, "on the mean streets of Neptune Beach," had been looking for direction in his life as a young man and found it in the aviation program. It was suggested to him by his mother Ruth Stiehl, founding dean of JU's nursing school.

He looked into the possibilities of the new school and loved it from his first flight out at Craig Airport.

"You get to fly! You go to the airport for school," he said. "So I’ve never had a real job since. I mean I was a lifeguard, I mowed lawns, cleaned toilets, waited tables at Bono's. Then airline pilot. Which isn’t a real job. It’s a little-boy job.”

He smiled: You'd better believe the responsibilities and requirements are rigorous. But he was able to commute to work from Jacksonville, and work took him all across the U.S. and on many trips overseas.

“I flew everywhere in the world," he said. "FedEx goes everywhere. Sydney, Honolulu, Alaska, Paris, London, Frankfurt, Dubai, Saudi Arabia, Hong Kong, Tokyo, Philippines, Malaysia and Taiwan, India, everywhere.”

And you get to really see the places.

“Sometimes you get five days," he said. "Five days in Sydney!”

There were sacrifices, the biggest of which was spending long periods away from his family. But he got to see so much, and it was often challenging, such as flying over a hurricane or typhoon, landing in ice and snow, and dealing with crosswinds, he said, that you just wouldn't believe.

Then there's the joy he gets in flying. “I miss the flying itself, because I can’t rent a 767 and go fly it to Hawaii for fun," he said.

He explains the appeal: “So, you take something that’s going zero miles an hour, weighs 490,000 pounds, or whatever the airplane weighs, and you take off on this 2-mile runway. You go up to 7 miles above the Earth going 600 miles an hour, and you put it on a piece of strip two miles long, in Hawaii, and make it go to a full stop again. That's pretty cool."

And the best thing, he says, about flying cargo? "There’s no complaints from the back.”

Investing in your flying future?

It isn't cheap going to JU's School of Aviation: For those on the pilot track, figure on spending up to $80,000 for flight fees, on top of regular tuition, Tuohy said.

"We euphemistically call those non-tuition costs," he said wryly.

That cost can be a challenge for many. "The number one barrier to entry, for many young people, to get into piloting, is the cost," Tuohy said.

Change in latitude: The late Jimmy Buffett's seaplane pilot from Atlantic Beach recalls adventures with legend

Rhett Stiehl was asked: Is this an investment in yourself?

He gave a shy smile. “Uh, I would say more of an investment for my parents.”

Tuohy noted, however, that many of the bigger aviation programs delay the start of actual flying for their students in favor of classroom studies only. Not at JU. Even this early, freshmen who've met all the requirements have already been flying with instructors at Craig.

In addition, they have access to several realistic flight simulators to train on, at no extra per-use cost.

Jacksonville University: Celebrating life of 'mother Fran Kinne'

He said the program has students from as far away as Alaska and Saudi Arabia, and that about 20% of students are women.

With the current pilot shortage, competition among airlines for qualified aviators is intense. Tuohy said new first officers at regional airlines are getting paid $90,000 a year, and it only goes up.

To be sure, the $80,000 in-flight fees to get experience and the necessary variety of licenses is daunting for students such as Rhett Stiehl, Tuohy acknowledged, but the future should be bright for them.

"That's a big investment, but today the return on that investment is huge," he said. "That’s about $40,000 less than it cost my daughter to go to law school, and he’s getting there three years faster.”

This article originally appeared on Florida Times-Union: Pilot shortage a draw for Jacksonville University aviation school