Avondale fends off youth gun violence. Could it be a model for the rest of Cincinnati?

A spike in violence this year is leaving teens shot and bleeding at their bus stop after school.

The year's first quarter is one of the worst on record in Cincinnati for youth gun violence. The spate of shootings has left three teens dead and another 14 wounded. That compares to just three teen shooting victims during the same period last year.

The April 4 shooting at a bus stop outside Woodward Career Technical High School left two teens wounded, and another three juveniles have been arrested in connection with the attack.

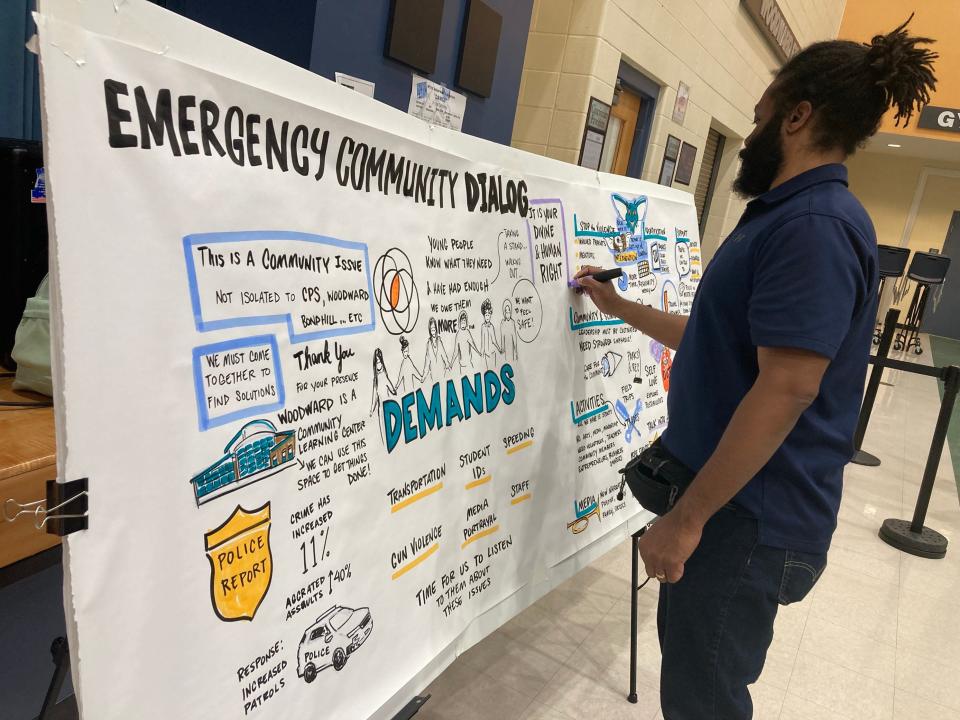

The mayor, police, educators and the community at large recognize the crisis and are vowing change. Students and community members gathered at the school a week after the shooting brainstorming ways to overcome the problem.

Looking throughout the city, at least one neighborhood, Avondale, has seen recent success. Several local community leaders told The Enquirer that it took collaboration among a variety of players to prevent shootings there. But they also said the city needs to find more money so the programs can scale up and reach enough teens in the city.

What's happening in Avondale

The shootings have been spread throughout the city: Westwood, Bond Hill, Evanston, West Price Hill, West End.

To answer why is complicated, but there are people who wrestle with the issue every day and have an idea of what is happening, what needs to be done and whether that kind of change can be sustained.

Maybe Avondale has an answer, neighbors there said.

The neighborhood is also on that list of places commonly tormented with gunfire but with a notable gap this spring. There weren't any shootings – involving teens or adults – in Avondale for the whole month of March.

More: At this point last year, 3 teens had been shot in Cincinnati. This year? 17

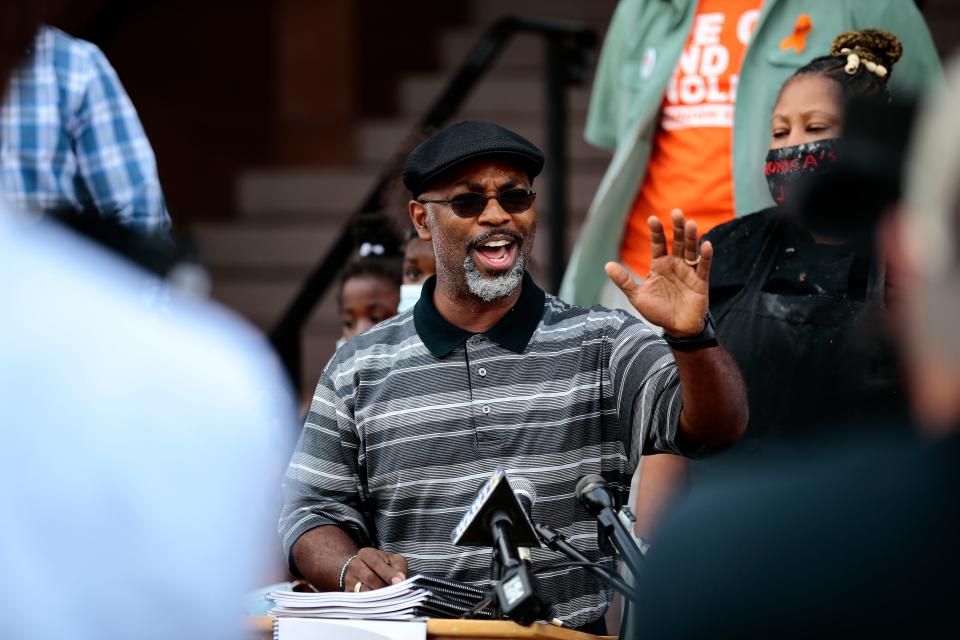

The Rev. Ennis Tait, pastor of New Beginnings Church of the Living God, said the neighborhood saw peace in part because of a huge effort by churches, the recreation center, police and other partners to come together and support kids during spring break.

Two churches took meals directly to buildings that have a high number of kids living there. Tait worked with property management companies to provide food to kids as well.

The library offered extended programming. The Hirsch Recreation Center was open during all the hours that school would have been open. Tait's innovation lab hosted times for kids to hang out or watch TV.

Tait said what happened in Avondale demonstrates two solutions that can prevent the violence from spiraling out of control: bringing organizations together and funding those already doing the work.

He said the strategies used during spring break worked, but more funding is needed to sustain those efforts and scale them.

Kids are in 'survival mode'

"We're searching for solutions when the answers are already here," he said.

Tait's organization, Project Lifeline, works with about 20 kids every week, providing food, haircuts and mentoring.

It is these kinds of mentoring groups that pull at-risk kids through the struggles they face to give them better outcomes, National Institute of Justice Journal research shows.

But Tait said his program and others like it in Cincinnati are chronically underfunded, and the work costs money. As an example, he said his church spends $400 a month on snacks alone for the kids in the neighborhood.

"Most of these young people are feeling the pinch of what their parents are experiencing, mostly with housing. A lot of our young people are homeless," he said. "Most of our young people are in survival mode."

More: More teens are facing murder charges. How it came to this

He said parents, pastors, police, principals, physicians and probation officers all need to come together to support the kids. It's not enough for there to be partnerships between some of the groups. The spring break drive was an example of how that kind of collaboration can work, he said. Kids need the wraparound services.

"It's been a hard journey," Tait said. "The consistency here is, we can't abandon them when they've done wrong."

Tait believes that even if teens get incarcerated or spend time in juvenile detention, they have to have a positive community to come back to.

Everyone at the same table

After the double shooting outside Woodward Career Technical High School this month, The Enquirer posed a question to a number of leaders in the city: What can be done to address youth violence?

A frequent answer? Work together.

There are too many groups and organizations working in silos, they said. That includes nonprofits and community organizations as well as governmental organizations such as police, schools and the court system.

The city does fund violence reduction initiatives through its $17.5 million human services fund, according to Cincinnati City Council member Meeka Owens. That money, which the United Way of Greater Cincinnati distributes, also goes toward workforce development and supporting high-risk communities.

Owens said city council needs to review how this money is spent. Recently the city passed ordinances requiring that firearms be stored safely and expanding restrictions on firearm possession for those convicted of domestic violence offenses.

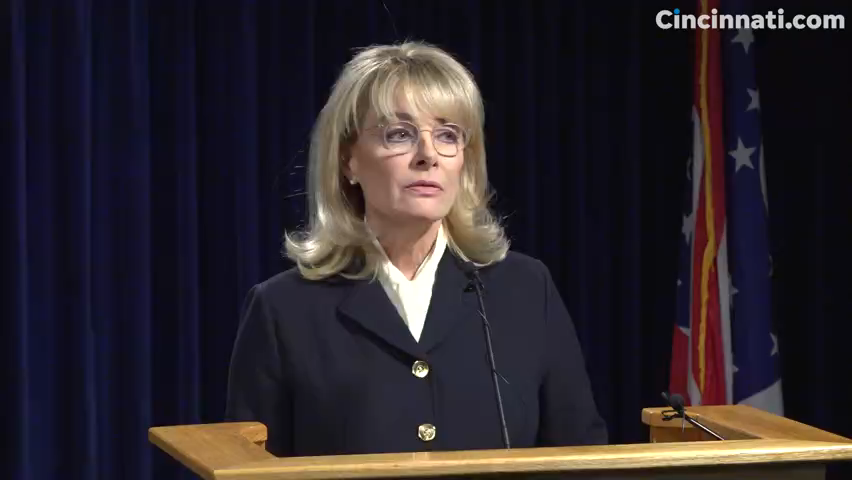

Cincinnati Police Chief Theresa Theetge asked council last week to continue to support the new crime gun intelligence center, a partnership between the department and federal partners, which uses new technologies to track how guns move throughout the city and focus on pinning down violent offenders.

Coming together

Tait said what's happening in Avondale can happen across the city. Lawyer Michele Young, who has worked with Cincinnati Public Schools on bullying, echoed his remarks.

"We have dozens and dozens of nonprofits," she said. "The resources are there, we just haven't brought them all together to say, 'We're not going to lose children to violence.'"

Hamilton County Juvenile Court Judge Kari Bloom said she hopes the court can provide a space for just such a collaboration to take place. She said the court is responsible for protecting children and the community.

"Our court does not have to be reactionary even though that is what it has been traditionally," Bloom said. "If we continue to sit back and process cases, we're saying there's nothing we can do."

Bloom said she's creating a violence prevention team to work with the court's community partners and go into the community to directly work with people. She said she expects to have it operating by the end of the summer.

Mental health supports are lacking

The juvenile court struggles to find enough mental health providers, Bloom said.

"We're a guaranteed payer and cannot find people to help kids, and those are only the kids we know about," Bloom said.

When it comes to the greater population, teens who have not found themselves in legal trouble, the story is the same.

The rise in teen shootings this year is heartbreaking but not surprising to Ashley Glass, who works in promoting health equity and is the founder and CEO of the advocacy group Black Women Cultivating Change.

There isn’t enough mental health programming in Cincinnati, Glass said, and teens are turning to violence out of curiosity, boredom, a need for attention and a lack of other outlets to release built-up trauma tension.

“I think a lot of our youth programming phases out around 12,” she said. “And so you have this age group from 13 to 18 where you have a lot of youth just not having mentors, programming and positive influences. So they end up getting into a lot of situations that they don’t need to be in.”

The programming in Cincinnati is mostly reactive, Glass said, not preventive. And even when there are resources available for kids, kids don’t know how to find them. Or they don’t have the capacity or language to ask for the support they need.

More kids arrested in gun crimes have no prior record

Ken Parker, the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Ohio, grew up in Cincinnati's East Walnut Hills and Evanston neighborhoods.

"When I was growing up, if a kid had a gun, everyone knew because there were only one or two in the community," Parker said. "Now the attitude in society is that everyone has a gun."

Kids get guns from their parents and car break-ins. They buy and sell them with their friends online. Probation officers and judges in juvenile court say it is astonishing how easy it is to get guns.

But Parker said the ease of access to firearms does not explain everything.

"Guns are only going to go as far as the mind takes them," he said. "There's something else there."

Parker serves as a co-chair of a subcommittee on juvenile violence and radicalization that provides input to the U.S. Attorney General's Advisory Council. He said the committee refers to youth who turn to violence as being "radicalized," a word typically associated with a person turning to terrorism or hate groups. The process is similar, Parker said.

"Their life has to have a purpose, have a meaning," Parker said. " When they lose that, that's where you have problems."

Parker and Bloom both said they are seeing this process happen more rapidly in recent years.

"More kids are going from zero to 100," Bloom said.

"Coming out of COVID, young people seem to be quicker to go to violent measures than they were before," Parker said.

They said that, in the past, teens who shot people often had long records in the courts. There were truancy issues, theft issues or other criminal activity that led up to the violent offense. Now, Parker said, more of the kids charged with gun offense have "no resume" – no prior record.

"More kids are coming in and their first charge is felonious assault," Bloom said.

Bloom said it's not a failure of the juvenile court system to rehabilitate youth because so many haven't had contact with court before, but she said she believes it is a failure of some systems.

There's some disagreement over what should happen to these kids, however.

Hamilton County Prosecutor Melissa Powers said juveniles who commit gun crimes were getting too much leniency in juvenile court.

"Community-based treatment for kids who shoot people is not an effective strategy," Powers said. "Juveniles arrested for gun charges should not be released back into the community. Until we accept that, we will continue to see these trends rise."

Bloom declined to comment on Powers' statement.

Pandemic takes a toll on at-risk kids

The COVID-19 pandemic had major impact on gun violence nationwide. Cincinnati saw record numbers of homicides in 2020 and 2021, and it wasn't the only city to see the trend.

While homicides have decreased in the past year and a half, the people in Cincinnati working with kids said COVID-19 and the disruptions it caused to school and home life are having a lingering effect on kids.

Bloom said the social services offered during the pandemic changed. There were additional community supports: a push to get internet in every home, evictions were put on hold, partners got stimulus checks and monthly child tax credits. Now those efforts are being scaled back. Kids are sometimes getting lost in the fallout.

Carlton Collins, a local activist and program manager for The Literacy Lab’s Leading Men Fellowship, believes the pandemic played a different role in the surge in gun violence.

He said everyone had to learn new ways to survive during the pandemic, and for some kids, those survival tactics "had nothing to do with anything positive or safe." Kids in negligent homes were left in traumatic situations with no escape to school or anywhere else during that time, and now the city is left with the fallout.

"I don't think this is the end of it," Collins said. "I think we may have another year before we stabilize."

'Chasing an illusion'

After the shooting at Woodward, Mitch Morris rushed to the scene. He works closely with Tait and runs Save Our Youth – Kings & Queens, a mentoring program for youth.

He has also spent decades responding to homicides and working with the surviving family and friends to prevent retaliatory violence.

Morris said the kids he encounters are often "chasing an illusion" of gang life as it is portrayed in music and movies.

"They think they want to be like that until they put their toes in," Morris said.

But he said he is hopeful because so many people throughout Cincinnati are working – more and more often together – to fight the problem. He said several members of the city council and the city manager all take the issue seriously.

"We've got the right people at the table."

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Could Avondale's action to end gun violence be model for Cincinnati?