Mueller report: What will it say about the Trump campaign and Russia's efforts to sway the 2016 election?

WASHINGTON – Three years ago, a lieutenant in the Moscow office of Russia’s military intelligence service sent a stream of innocuous-looking emails that altered the course of American politics.

The messages were meant to look like security alerts from Google, and they directed recipients to a website controlled by the Russian government where they were asked to enter their email passwords. They went to hundreds of people associated with Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign and were alarmingly effective: Within days, the fake alerts enabled the Russian government to harvest tens of thousands of emails from Clinton's campaign chairman.

You know what happened next – a 22-month investigation into Russian election interference during the 2016 campaign and whether there was any coordination with Donald Trump or his aides.

That work comes to its climax on Thursday, when the Justice Department says it will reveal special counsel Robert Mueller's detailed report.

The Tump team's Mueller report game plan: Read the report quickly and put out responses

Democrats: As the Mueller report looms, Democrats find voters would rather talk 'kitchen-table' issues

In his summary of Mueller’s conclusions released in March, Attorney General William Barr said investigators had gathered evidence of “multiple offers from Russian-affiliated individuals to assist the Trump campaign,” but left unanswered what became of them. Those answers have remained secret as the Justice Department has weighed how much of the report to make public.

Until that happens, the charges Mueller’s office filed – and the charges it didn’t – offer the best indication of the central findings of an investigation that raised the extraordinary question of whether Trump was involved with Russian efforts to sway the election in his favor.

Barr said in March the answer to that question was unequivocal: “The Special Counsel’s investigation did not find that the Trump campaign or anyone associated with it conspired or coordinated with Russia in its efforts to influence the 2016 U.S. presidential election,” he wrote in a letter to Congress.

The release of Mueller's full report – nearly 400 pages covering evidence obtained through hundreds of interviews and thousands of demands for documents – could give Congress and the public answers to more nuanced questions: If the evidence did not establish a criminal conspiracy with Russians, what did it establish?

Barr’s summary and hundreds of pages of court documents Mueller filed during his investigation showed it sprawled beyond the provocative issue of Trump’s ties to Russia. The investigation documented Russian outreach to Trump’s campaign, and the eagerness of aides to benefit from the efforts. And it accused some of those aides of lying to downplay those connections.

“No serious person disputes now that the government of Russia engaged in an aggressive and far-reaching campaign of interference in the 2016 presidential election,” said David Kris, the former head of the Justice Department’s national security arm and a founder of the consulting firm Culper Partners. “I don’t think there’s much question at this point of the tactics they adopted.”

Mueller report: Read Attorney General William Barr's summary of the Russia investigation

Protecting Trump: Why so many aides lied to protect Trump in Russia investigations

Separate investigations into Russia – including possible connections to Trump’s campaign – are continuing in both the House and Senate.

Sen. Richard Burr, R-N.C., head of the Senate Intelligence Committee, said its investigators have nearly finished their work and will turn soon to preparing a final report, something he said would take “a couple of months.”

Because details of Mueller’s report remain secret, many of the central questions surrounding it remain unanswered. Here is what we know so far, based on Barr’s summary and on available court records:

What Russia did

In his summary of Mueller’s report, Barr said investigators found evidence of “two main Russian efforts to influence the 2016 election.”

One was the hacking campaign that began in March 2016, when Russia’s military intelligence service, known as the GRU, began sending “spearphishing” emails and probing the online security of Clinton’s campaign and other Democratic political organizations, according to charges Mueller’s office filed against a dozen intelligence officers. Government hackers stole emails from the Democratic National Committee and Clinton’s campaign manager, John Podesta, then passed them to the anti-secrecy group WikiLeaks, which posted them online at opportune moments.

The other was an effort by the Kremlin-linked Internet Research Agency to spread disinformation and discord online, largely by churning out social media posts picking at Americans’ political divisions. Mueller’s office indicted 13 Russians for participating in that scheme and revealed that investigators had tracked their finances and emails. In one, the company told employees its goal was to “spread distrust toward the candidates and the political system.”

Why Russia did it

U.S. intelligence agencies concluded in an unusual January 2017 report that “Putin and the Russian Government aspired to help President-elect Trump’s election chances when possible by discrediting Secretary Clinton and publicly contrasting her unfavorably to him.”

In court filings, Mueller’s office revealed some of the specific evidence supporting that conclusion.

Prosecutors said in an indictment last year that the GRU sought to “stage the release... to interfere with the 2016 U.S. presidential election.”

The filing quoted messages between GRU operatives and WikiLeaks talking about the stolen records and when they should become public. In one, someone working for WikiLeaks said it hoped to release more records before the Democratic Party’s nominating convention, to maximize its political impact. A Russian officer replied that they thought “Trump had only a 25% chance of winning,” and so saw value in playing to conflicts within the party.

Other signs were still more explicit. Mueller’s office said in its indictment of the Internet Research Agency that internal emails were explicit about the group’s aims. In one, sent in February 2016, managers admonished their workers to “use any opportunity to criticize Hillary and the rest (except Sanders and Trump – we support them).”

Campaign connections?

Some connections between Trump's campaign aides and the Russian government have been apparent since the investigation's early phases. Harder to discern is what to make of those contacts. Something? Nothing?

Mueller’s office has supplied some of the answers already in charges it filed and allegations made in court – as well as in the absence of charges. Investigators pointedly never accused any Americans of knowingly participating in Moscow's election plot. But in a series of criminal charges, they mapped threads running between that effort and some of the people surrounding Trump.

In one case, the investigation revealed that shortly after the hacking campaign began, a professor approached a foreign policy aide to Trump’s campaign, George Papadopoulos, and boasted that Russia had obtained “dirt” on Clinton in the form of “thousands of emails.”

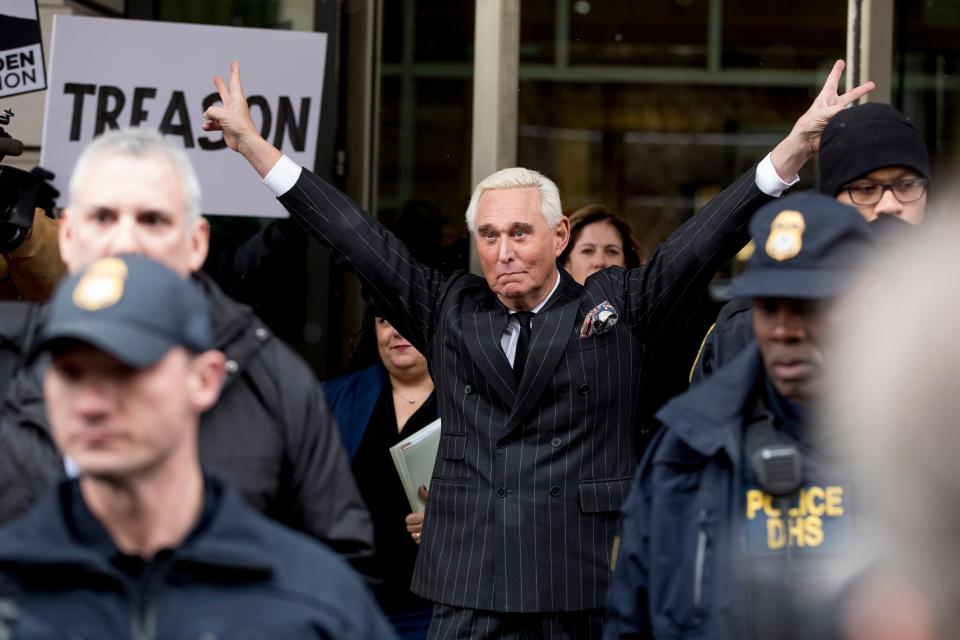

In another, it alleged that one of Trump’s longtime political advisers, Roger Stone, had been asked to get in touch with WikiLeaks to keep the campaign apprised of when the group would release more hacked documents. “On multiple occasions, Stone told senior Trump Campaign officials about materials possessed by (WikiLeaks) and the timing of future releases,” prosecutors wrote in an indictment revealed in January.

They also said Paul Manafort, then Trump’s campaign chairman, had passed polling information to a Russian they believed was connected to Russian intelligence.

All of them later lied to investigators about those exchanges, prosecutors charged. (Mueller’s office didn’t prosecute Manafort for lying; instead it asked a court to use his false statements against him when he was sentenced on other charges.)

In other cases, Mueller’s office filled in details about exchanges that played out mostly in public.

In July 2016, Trump suggested during a televised news conference that perhaps the Russian government could find emails that had been deleted from Clinton’s private server. "Russia, if you’re listening, I hope you’re able to find the 30,000 emails that are missing,” he said.

Later that day, prosecutors wrote in an indictment, GRU officers “attempted after-hours to spearphish for the first time email accounts at a domain hosted by a third-party provider and used by Clinton’s personal office.”

What to make of those contacts has been an open question ever since. Last year, Republicans on the House Intelligence Committee said they had found "numerous ill-advised" contacts, particularly with WikiLeaks.

The question Mueller sought to answer was whether those contacts amounted to anything more: Had Trump or anyone from his campaign joined in those efforts in a way that would be a federal crime.

The answer, revealed in March, was no.

Contributing: Bart Jansen, Kristine Phillips

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Mueller report: What will it say about the Trump campaign and Russia's efforts to sway the 2016 election?