Awol Erizku Is Creating a New Language

“I'm interested in historical intervention,” the photographer and conceptual artist Awol Erizku says, sitting at a long table on the 10th floor of The FLAG Art Foundation, where his new exhibition, “Awol Erizku: Mystic Parallax,” is on view. “And most importantly, a global Afropolitan perspective. I'm interested in the Black imagination and the wealth of history that being Black can afford us.” He’s explaining what he calls “Afro-esotericism,” the philosophy governing his new show. The idea comes through clearly in the display of photographs, drawings, videos, and sculpture that present a series of familiar symbols of his practice—Nefertiti, African masks, a David Hammons–ian hint of rumor and humor—as “anti-dogmatic, anti-didactic, anti-rhetorical” provocations. “What I'm trying to do with Afro-esotericism,” he says, “is say, 'No, we can take it all the way back to the origins of Africa and precolonial history and find ways to work from the origin.’”

The exhibition also introduces a new motif to Erizku’s grammar: fire. In place of the mixtape Erizku usually creates for each of his shows is a soundtrack composed by Christian Scott that plays, while the aromatic smell of burning incense wafts through the air. Here, fire and sound are used to establish mood, which is representative of an artist who is about a vibe—one that summons the spirit and the flesh. Mounted on the white walls are varying views of the element. “Nefertiti (Lit Freestyle)” (2018-2020) is a street scene of a white bust of the Eyptian Queen set aflame. It seems to visualize what Erizku calls, rejecting the gaze of “a whitewashed colonized history.” In other works, like the still life, “Malcolm x Freestyle (Pharaoh’s Dance)” (2019-2020), black self-empowerment seems to be on Erizku’s mind. “Pardon my ladder (Arm n Hammer)” (2019-2020), featuring two black glocks contrasted with the muscular chest and arms of a black male, is a study of literal fire power.

Digital Chromatic Print

26x20 inches

Erizku is interested in nothing less than creating a vernacular of and for the African diaspora. “Afro-esotericism is like an encyclopedic index of ideologies, objects, and people that I encounter,” says the frequent GQ contributor. “This idea as seen in this show is Afro-esotericism as unmanufactured avant garde. It is using the origin of one's history and one's self and one's identity as a central point to create something new.”

GQ spoke to Erizku about Afro-esotericism, the themes in the new show, fatherhood and his Nipsey Hussle and Lauren London commission for the magazine.

A central theme of the work seems to be about rerouting black knowledge and art away from whiteness. In art and life, the white scholar or curator has had a lot of say in how we see blackness in art history and contemporary life.

The black imagination is connected through a golden thread of universal unconscious that can be awakened and nourished. Going to Cooper Union as a student, you would go to a lecture and be taught African history by an old white man who's doing a dance, who's doing a chant...

The historian Robert Farris Thompson.

Yeah. At that point, I didn't have the vernacular to address what I was feeling, but it was a visceral feeling of “Yo, this doesn't feel right.” Then, I went to Yale, same situation. And although I don't have any issues with his work, he cites a lot of people I admire, but why is he seen as the authority to teach me about my culture? As I've been in my studio in LA, in my own sort of isolation, I've been reflecting on these things. And I'm like,"Well, if I'm supposed to look back at Picasso to move forward, how the fuck does that make sense when Picasso was stealing from Africans?" The engagement should be with the African artist first. For me, it's about starting from the origin as opposed to saying, “Oh, I did this because Man Ray made images with African masks.” Fuck Man Ray.

The show in some ways continues your early exploration of some of the ideas David Hammons established in art. Why do you return again to Hammons time and again?

Hammons is a gateway to a real, deeper black art. What I love about Hammons is he always connected an African lineage to African American culture. He's Black American but in his addressing of his concerns he often centers Africa. There's this piece, “Dak’Art 2004 Sheep Raffle,” that he did in the Dakar biennial where he raffled off sheep during Ramadan. I think he might've done it during Eid, when it is tradition to sacrifice a certain animal. For him to turn that gesture upside down as art connected it for me to my grandmother, who does shit like that whenever I go visit her in Ethiopia.

Metal fence with barbed wire, assorted tees on hangars

82 x 98 x 9 inches

You can see it in the symbols you use, like the Nefertiti throughout the show. And the work “Mystic Parallax: Visual Manifesto” (2020), where you have the little girl chanting the Shahada creed, and the “Ramadan Drawings” (April 23-May 23, 2020), made through a sort of meditative, performative ritual, every day during the holy month, with a basketball and incenses. The bringing-together of symbols across African and African American culture to engage in dialogue is felt.

It's deliberate. It's about reclaiming some symbols as a way to reconnect them back to Africa—like Nefertiti—but also a deliberate way of showing the hand and the affinity that I have towards the older generation and the artists that I know have opened the way for me to do what I'm doing now. I am bowing to my elders.

But I think in this show, you do take a great deal of freedom. You use lineage as a point of departure.

A huge aspect of this work is very declarative, intentionally. The visual manifesto came from this place of, we all can't be talking about this thing called blackness as a homogenous. We have to get deeper, so we have to talk about spirituality. If you listen to “Bird Talk, Time I Danced for the Moon” (2020)—a video where the voice of a black Muslim man meditates on journeying up the hill to the Hollywood sign, racism and the inclusivity of Islam—he's talking some real talk. It's a nuanced conversation and it speaks to my whole mission behind Afro-esotericism. It's about not being too married to an idea or conforming to an idea that's been championed over decades without knowing its history. Why do you feel the need to champion an idea that you're told black artists have to champion?

Like the idea of positive representation?

Right, like: why do we need to be represented in certain spaces in order for us to matter? No, we matter. Our ideas matter. And I think that by engaging in that sort of rhetoric, you're excluding the black imagination. Why aren't we talking about going to the moon, why aren't we talking about more nuanced, complex things outside of that kind of representation?

In this show common positive tropes are out. In “Heat” (2019), a diptych of the young black woman holding a glock, juxtaposed with an image of burning candles coming together to form a cross, you use fire to express possibilities that range between the spiritual and empowerment. Why is it important to present this image?

I think it's dangerous when everybody is asking for permission. I use fire as a medium and both literally and metaphorically. Fire as a way to think about a way to cleanse something, as a way to destroy something in order to rebuild, rebirth. All the images in the show are like visual poems—they're meant to be read, not just looked at. In “Heat,” the contronym comes in. Heat, [as in] the gun, heat, and then there's the fire-heat, but what transpires between those two images while you're looking at them simultaneously is this idea of coming together in revolution, action.

And you are saying, where's the counter-images to the death we see visually?

Yeah, where's the counter-image of black people with guns, and where is that image being in fashion? I think it's trending, especially now with social media. I admit, I'm not foolish enough to think that art is going to change the world, but I think it could implement newer ideas, newer visions, and that's my stake in it.

Photography is about visualizations of desire.

These works are a constellation. They are propositions. Maybe we stop telling people that we matter and we just arm up. The George Floyds and Breonna Taylors matter. It's just, at a certain point, I wonder: what are we supposed to do with those representations of their deaths?

There's a real concern that Breonna Taylor was made into an internet meme.

Listen, we have become so quick to throw up a flag when there's a bombing in Lebanon or Paris, or throw up a black square, but what are we really doing? I think in that way, social media has fucked up our collective subconscious. Virtue-signaling is at an all time high. We have to shift away from that—and, again, art could maybe help us initiate certain conversations.

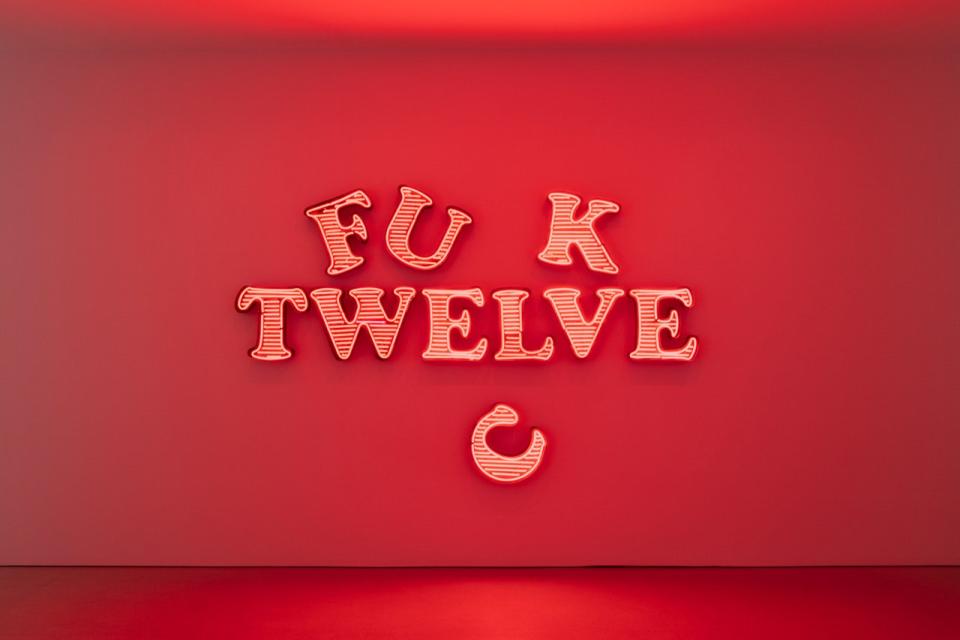

The introduction of the show, is a neon “Fuck Twelve” (2018), made two years ago, before this sort of conversation around abolishing the police came into mainstream conversation. Why did you create it then?

It's about the trap music element that is another thread in the show. Atlanta rappers definitely made “fuck 12” hot, like Gucci Mane, Migos, and Fatman Key. Fuck 12 was first experienced on a sonic level. I noticed it because of DJing and just listening to those artists. I was like, "Oh, this is like the new iteration of 187 on the undercover cop." No one says 187 in our generation. It was the interest in that and the interest in a vernacular that no one really engages with in art, which goes back to the way the Eurocentric gaze dismisses us.

Black music is one of the few spaces of black freedom. It's black language that hasn't been filtered through whiteness. I do think the use of the neon that turns spoken language into an object is interesting. Music, jazz, rap and trap, is something you have drawn on from the beginning. Why?

I grew up listening to Jay, and most importantly Nas. You go back to his album I Am… and he's essentially King Tut on that cover. It was his way of engaging with blackness, and Islam too. That’s what I also love about Malcolm X's messaging. It presents the human question. He is trying to show us like, “Yo, this world is possible if we could have a global perspective as black people.” We have to see ourselves beyond the lens of America. That's the message that I want to echo with anything that I do.

You have this long engagement with African masks. In this show they appear in your still life work, “Head Hunters” (2018-20) and “Black Fire (Mouzone Brothas)” (2019), among others. Why do you continue to return to these objects?

There's this quote, “In the 21st century, the saxophone and the African mask are the two symbols of blackness, those are the icons.” In my work, sometimes they're a stand-in for the black figure, where they become an opportunity to reimagine the body and the spirit. Also, it's not like, "Yo, I went to Africa and I got these masks." I like the fact that these are commodifiable objects, a part of global trade. I could buy from Ibrahim who sells them outside of the Whitney or the other Ibrahim who sells out of MoMA. The only difference between somebody that say they are using African masks in some sort of spiritual way and the person who's allowed to formally consider them and put it in a gallery is a fucking MFA. They're doing their thing and I'm doing my thing.

Digital Chromatic Print

40 x 53 inches

As long as I've known you, this show is the most explicit that you've addressed being Muslim. Why?

It's always been in the mix tapes. But one reason it's now in the visual language is fatherhood. I've lived with her for eight months now and I was going through this transition of how am I going to explain the world to a daughter? How am I going to help her understand her identity? That's been on my mind. I'm not the most religious person, but I'm Muslim by blood, and I want her to understand her lineage. For me, it became about creating a space through my art that I can address things with her once she's of age.

The art on display has a lot of content with deep social implications. But formally, your use of color in relation to the figure has grown less pop-like, say in the way of Kwame Braithwaite, and your construction of images less invested in portraiture. We see, in this show, an affinity for still life photography. What brought that shift from an image like “Girl with A Bamboo Earring” (2009) to works like “Quotidian Drip” (2018-20)?

When I moved to LA, I lost a connection to the subjects that I would come across on the trains, at openings, and daily life in New York. Living in LA in some ways had forced me to find a new way to engage with the concepts and the ideas that I have about my work and my contemporary understanding of the world. I'm not saying, "Yo, these are masks from the ‘60s and Ralph Ellison had them," or wherever. That's cool, but let's keep it real. My audience is always the people that I grew up around—these are people from the projects that could come to the art however. But when I moved to LA, I also became more interested in oscillating between the figurative and the abstract.

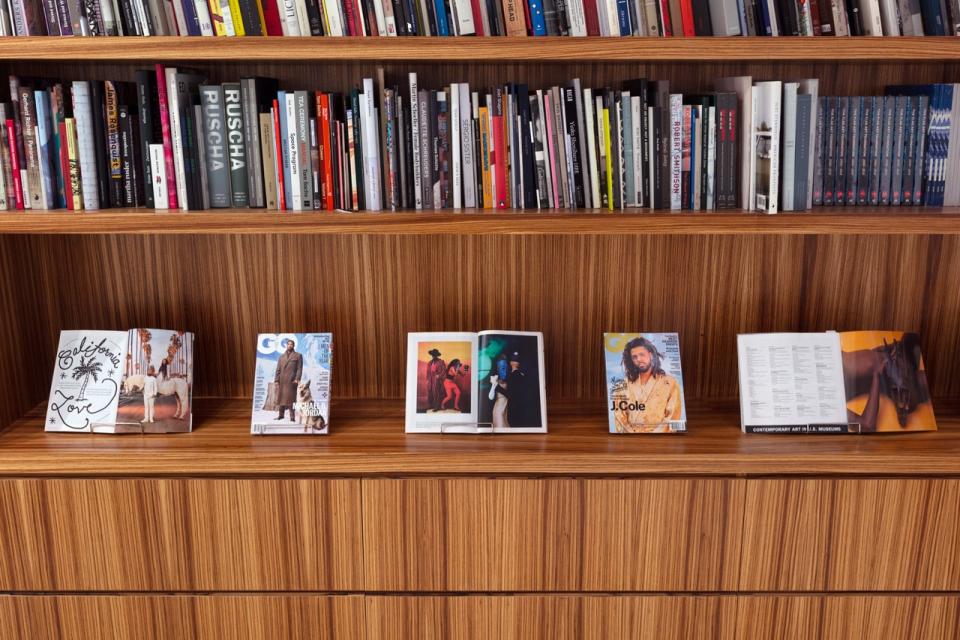

One of images, “Artemis” (2019), is a lightbox of a white horse standing outside of a house in LA. It's from your Nipsey Hustle and Lauren London GQ shoot. Why was it important to represent them that way?

In this current climate, it's to evoke a certain feeling. I'm very careful about how I use the black body. The reason why the GQ covers are on display is because I want to show that if I'm using black figures, it's to portray black people as the masters of their domain. I was fortunate enough to work with Nip and Lauren at a point in their career where I felt they were just breaking into the mainstream as a couple. And at that point from my perspective, I didn't see the kind of couple that was not just beautiful, but they had such elegance, grace, and connection to community. I wanted to honor that in LA, to show the city as a space with deeply rooted black communities.

After his tragic passing, those images became a way people memorialized him.

His death was heartbreaking. We had plans to work on his album. But at the same time, I feel very honored that those are the images that will be remembered when you think of him.

Lightbox

26 x 20 inches

“Breaking News” (2019) is a small gesture that could be missed. It's a 4x6 inch unframed print of a black woman being interviewed on the local news about a mass shooting in Dayton, Ohio, you taped on the wall between the elevators. Why end with that particular image?

You peeped that? It was a note to end on because it is a constant reality for us. There was a time where I couldn't turn on the TV without seeing black people being shot up. That image is just a moment I documented it. It wasn't meant to be timely, but again, it is yet another reminder as to why black people need to get a hammer. You know what I mean? Just get your hammer and stay ready.

“Awol Erizku: Mystic Parallax” is on view at The FLAG Art Foundation through November 14, 2020.

Originally Appeared on GQ