Aztec Ruins historic inscriptions survey yields plenty of results — and a few surprises

FARMINGTON — Aztec Ruins National Monument may be the subject of a centennial celebration this year marking its establishment in 1923, but the 318-acre, ancestral Puebloan site still possesses the ability to surprise those who have spent years documenting Chacoan culture, as a new study reveals.

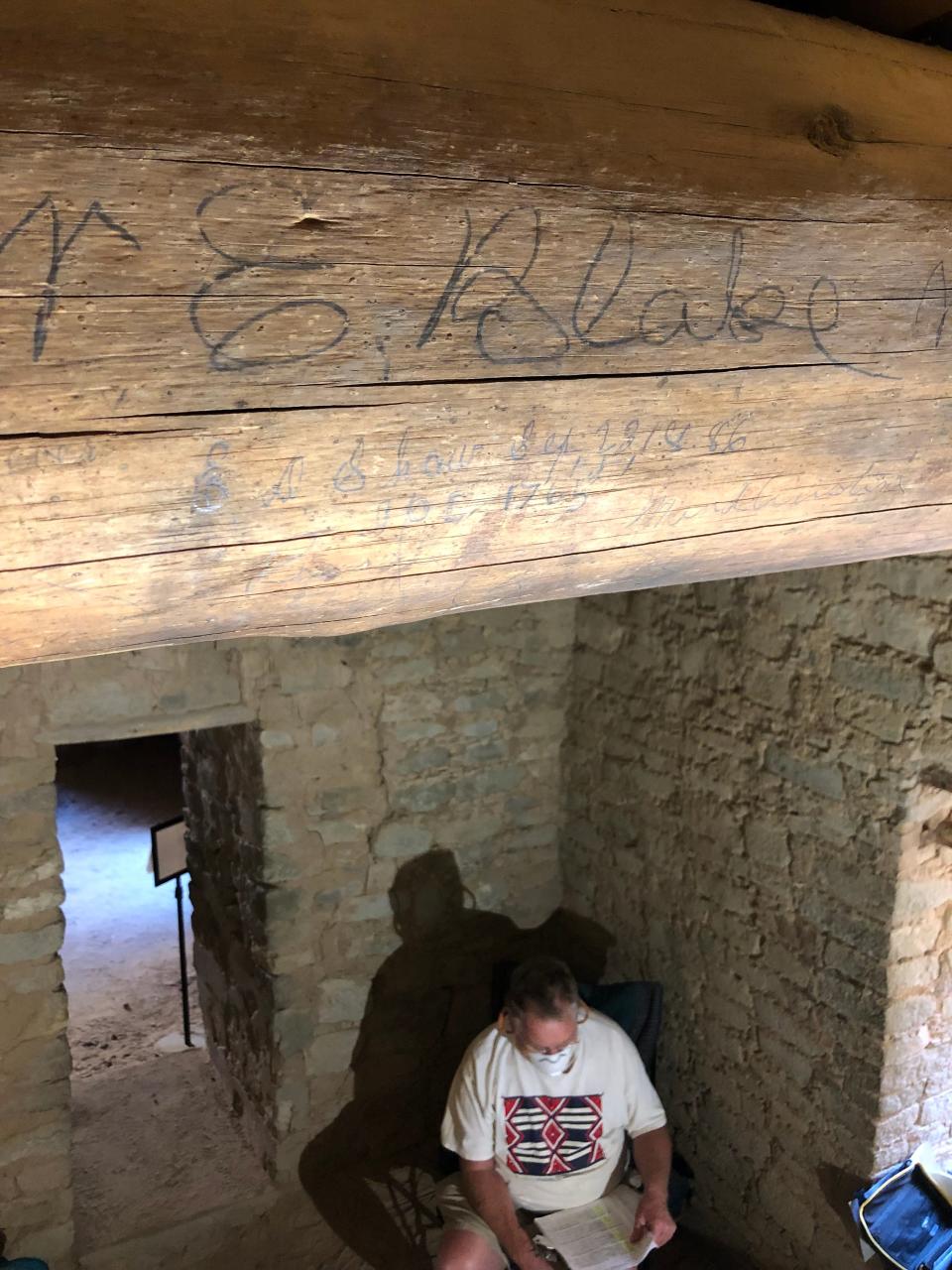

A team led by Fred Blackburn — a Cortez, Colorado, historian, author and researcher who has dedicated much of his life to unlocking the mysteries of the Colorado Plateau and the people who lived here before the arrival of Europeans — has released a 270-page report outlining its findings from a three-year study of historic inscriptions found at the 900-year-old ruins.

The project was funded by a federal Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit grant awarded to the firm Archaeology Southwest in Tucson, Arizona. Blackburn served as an independent contractor working through the firm, and the Aztec Ruins staff cooperated with him on the project.

It’s clear the experience of the past few years has left its mark on him.

“I believe that history and archaeology are both an ongoing discovery and that a detailed interdisciplinary look at all aspects of Aztec Ruins National Monument will continue to surprise us both historically and prehistorically,” he said.

The inscriptions include approximately 500 names that were found written or etched into structures across more than 1,800 locations at the park over a roughly 60-year period from the late 1800s to the early 1900s. Each of those inscriptions — essentially antique graffiti rendered with a lead pencil, quill pen, knife or other carving tool — has been photographed, measured, documented and interpreted.

But the most significant, and unexpected, finding from the survey extends from another, previously unknown, chapter in the history of Aztec Ruins. Blackburn’s team identified 300 examples of what it is calling ancient Puebloan “stealth” art created by a variety of processes and found on wood beams and masonry walls or stones in the ruins.

“The biggest thrill and surprise is finding that prehistoric art,” Blackburn said. “And we’d never have found it if not for us dealing with this at a microscopic level and using digital cameras. That’s why everybody missed it.”

Blackburn, a former Bureau of Land Management ranger, worked in the Natural Bridges National Monument in southeast Utah before helping establish the Crow Canyon Archaeological Center near Cortez and the White Mesa Institute at the College of Eastern Utah. He and his team began their physical examination of the Aztec Ruins inscriptions in May 2019 and continued the work through the fall of 2022. Since then, his attention has been focused on organizing those findings, and writing and editing the team’s final report — the culmination of an effort that has dominated his life for the last four years.

“It’s a huge relief,” Blackburn said of being able to hold the hefty report in his hands, though he noted there are still many photographs to integrate into the document.

The grant funding for the project ran out last fall, but Blackburn and his wife Victoria Atkins, an archaeologist and an important member of his team, continued their work anyway, spending an additional couple of hundred hours preparing the report, which was authored by the two of them, along with Paul F. Reed. Blackburn said the experience has been the most compelling of his career.

“This one beat everything for interesting,” he said. “And it was complicated, very complicated.”

No simple process

As he notes in the final chapter of the report, Blackburn initially believed he could complete all the work for the project in 2019. But once he and Atkins began surveying the ruins, he quickly was disabused of that notion.

The number of inscriptions and the number of rooms that featured inscriptions were much higher than he anticipated, he said, and that realization came to him even before the COVID-19 pandemic struck in the spring of 2020, further pushing back the completion date.

“All of us thought we’d be done in a couple of months,” Blackburn said, scoffing at the folly of that assumption.

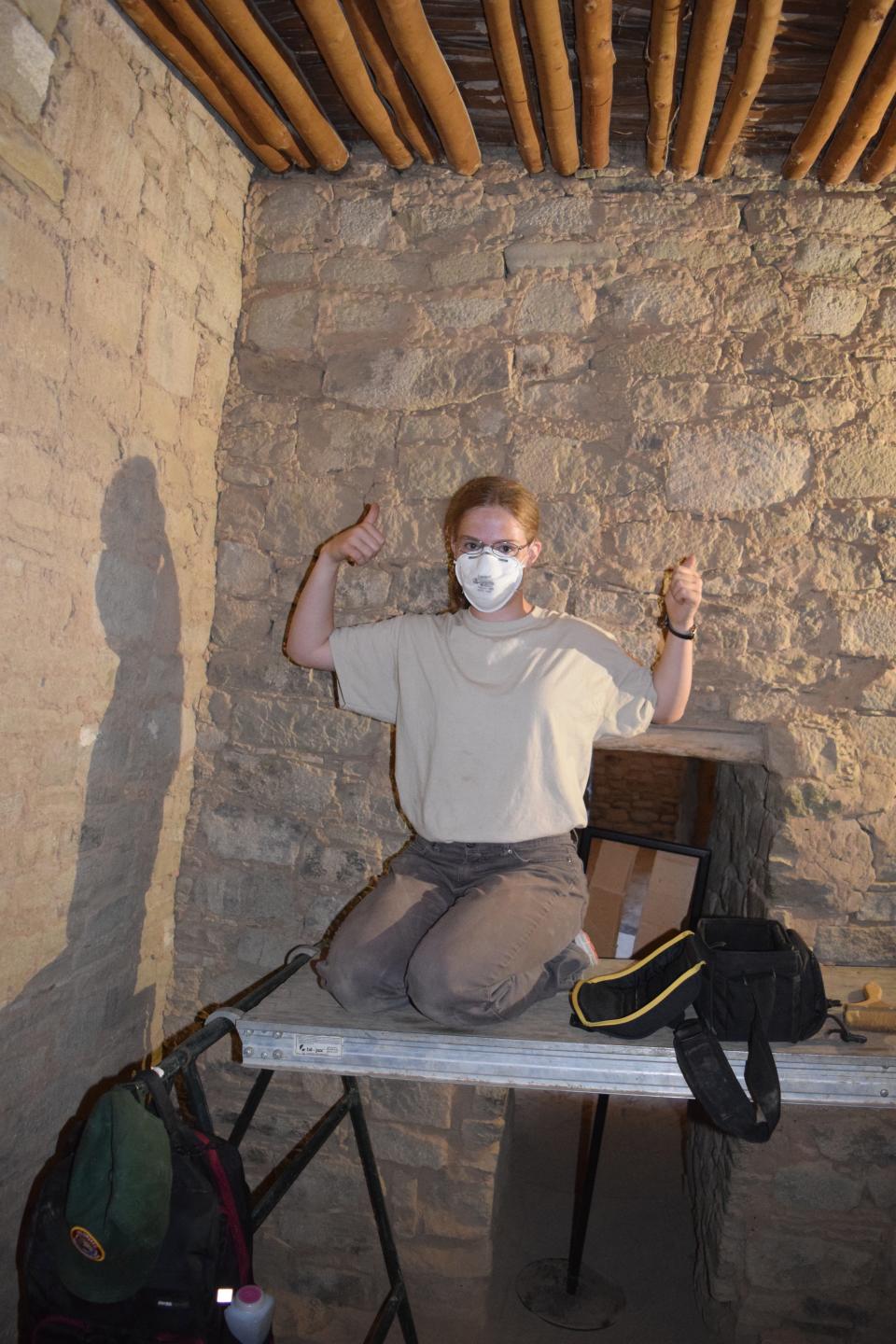

Eventually, Blackburn and his core team — which consisted of Atkins, Zoe Matney, Moriah Sonnenberg, Logan Dean and Chuck Haspels — would survey five rooms in the original Earl Morris house that now forms the core of the park’s visitor center, named for the famed archaeologist who led the first dig at the ruins with the goal of understanding the past, and 13 rooms at Aztec West. The rooms were chosen, Blackburn writes in the final chapter of the report, because of heavy visitation by thousands of people each year.

Surveyors examined every square inch, and every nook and cranny, of the walls and ceiling of each room with the assistance of portable lighting, ladders, scaffolding and magnifying glasses. They battled dust, heat, cold, insects, even the occasional bat. It was a painstaking process that they refined through trial and error until they had developed the most efficient methodology that assured a uniform examination of each room.

“The field methodology for this project improved as our work proceeded from 2019 through 2022,” Atkins and Blackburn write in chapter two of the report. “After initial efforts, the team found the right mix of team members, division of labor, cross-checking procedures, and workflow. The methods outlined here evolved along with our work.”

Eventually, their work would identify 1,804 locations in those 18 rooms where someone had scratched or written a name or left some other message denoting their presence. The earliest date the team found was February 1861, and although there appears to be more to that entry — additional writing of similar style and placement was found adjacent to that date — it is illegible, Blackburn said, meaning it reveals almost no specific information about its author.

Nevertheless, Blackburn believes he can determine some biographical details about the writer simply by placing it in a historic context and examining the inscription itself.

“It looks military and it feels military,” he said. “And whoever it was was seeking immediate shelter. It’s only one date in one room, so they were likely passing through.”

Blackburn said many of the inscriptions his team found at the ruins were similar to that one — a date that could be read relatively easily and other writing that was illegible.

“Dates are easier to read because they’re just numbers,” he said, noting that most of the inscriptions were found on vigas supporting the ceiling, meaning the folks who left them often were reaching overhead to write — not a position that promoted excellent penmanship.

The next inscriptions at the ruins don’t come until later in the 1800s. An Aztec schoolteacher named John Johnson led several of his students on an exploration of the site in 1881, but Blackburn said nearly all the inscriptions date from between 1878 and 1915, long before the site had any federal protection. Most of the inscriptions are found on vigas, he said, because those early explorers often gained access to the sealed rooms by knocking a hole in a wall and standing on the rubble to write, typically leaving their name, the date and their hometown.

The origin of the folks who left those inscriptions changed considerably in the early 1900s, Blackburn said, because of the arrival of the railroad in the City of Aztec, which was established in 1887. For the first time, visitors from far-flung locations had relatively easy access to the ruins, and many of them took advantage of that fact, leaving behind inscriptions that showed they hailed not just from places across North America, but overseas, as well.

One such message consists of “Edward Prince of Wales, London England.” Blackburn dismissed the idea that the inscription was made by the prince. Rather, he said, it likely represents a memorial to the duke of Windsor — and eventual king of England — crafted by one of his subjects.

Another inscription in Aztec West is equally curious, consisting solely of, “Woodrow Wilson, Washington, D.C.” with no date. Blackburn said an examination of Wilson’s recorded signature allowed him to quickly rule out the slight possibility that the 28th president actually had visited the ruins and signed a latilla. He believes it is more likely the inscription was intended to honor Wilson, and he discounts the possibility that the signature was intended as a prank or practical joke. Blackburn refers to the Prince of Wales and Wilson inscriptions as “memorial signatures.”

The ruins apparently even attracted some local rabble rousers, as evidenced by the discovery of two inscriptions left behind in an Aztec West room by local socialists — one that urges, “Workers Unite” and another that proclaims, “A Socialist is your best friend.” Blackburn has speculated that members of the local socialist movement — accustomed to being harassed by law enforcement officials or local residents who did not take kindly to the political message — used the room as a clandestine meeting place.

Others left more detailed signings, such as an 1894 inscription by a woman named Phila Bliven, who left behind a 105-word message in which she compared the ruins to those of ancient Babylon.

“Surely the people who built these might temples and palaces were a very ancient race possessed of a degree of civilization equal to the ancient Egyptian civilization,” she wrote.

The people behind the inscriptions

Such lengthy inscriptions provided Blackburn with plenty of material from which to work when he set about engaging in another important aspect of the project — researching the lives of many of those authors and writing short biographies of them. Bliven was one of those folks, 25 in all, who have been commemorated in the report.

Born in Illinois in 1853, Bliven made her way west, marrying twice, according to her bio. She lived first in Colorado, then in Wyoming, where she appeared to reside at the time she left her inscription at the ruins. That fact turned out to be significant, as years earlier, it had become the first American state or territory to grant women the right to vote.

In October 1893, Bliven wrote an article for The Great Divide describing her experience as female voter in Wyoming — the first and last time she would cast a ballot, she said.

“I am now, and always have been, opposed to woman suffrage … ,“ she wrote.

Later that month, she turned up in Durango, Colorado, to deliver an address opposing women’s suffrage during a meeting at the courthouse. As reported by the Durango Herald, Bliven described her belief that women’s suffrage would bring about nothing less than the downfall of the republic.

Her message was not well received by at least one party. A subsequent review of her address in the Herald was, as the bio notes, “scathing.”

“Mrs. Phila Bliven may be a success as a newspaper writer, but she certainly is a failure on the rostrum when discussing women suffrage,” the reporter wrote. “She did not advance a single argument for her side of the cause.”

Another biography chronicles the lives of members of the Gearheart family — pioneer homesteaders who ultimately abandoned their claim in San Juan County, but not before numerous members of the family left behind inscriptions at Aztec Ruins.

The group included William Vernon “Willie” Gearheart, who relocated to Lamesa, Texas, in 1919 and ran an auto repair business for 36 years. Gearheart was well known in Lamesa for manufacturing small cars, often finding himself the subject of flattering newspaper profiles extolling his ingenuity. According to his bio, the 17-year-old Gearheart appears to have left behind several inscriptions at the ruins on the same day in 1909 when he was just 17 years old.

Blackburn said his research into the Gearheart family, which revealed just how difficult it was for a homesteading family to make a go of things in San Juan County in the early 20th century, was particularly meaningful for him.

Also included are bios of members of the Abrams family, the first “owners” of the ruins site. That chapter includes correspondence over a several-month period in 1919 between H.D. Abrams, the family patriarch, and Clark Wissler, the curator of ethnology at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, concerning the proposed sale of the ruins site to the museum and its eventual transfer to the National Park Service as a national monument on Jan. 24, 1923. Blackburn’s team identified three inscriptions in the ruins that were signed by members of the Abrams family.

Nearly every room that the members of Blackburn and his team surveyed at the ruins were found to have inscriptions. He acknowledged the job of surveying the entire site is nowhere close to being done, explaining that six rooms still need to be examined in the West Ruin, and the East Ruin hasn’t been surveyed at all.

But by the fall of 2022, with the grant funding gone and a wealth of material already having been accumulated, Blackburn said he knew it was time to abandon the physical surveys and start compiling the report.

“It took writing it up to understand it,” he said of what he and his surveyors had discovered.

'This just isn't right'

As he settled into a recliner in the living room of his Cortez home one afternoon in the middle of July, Blackburn recalled that he and his team were only two to three weeks into their surveys of the Aztec West rooms when he realized they had stumbled across something even more extraordinary than the inscriptions they were seeking.

While he and Sonnenberg were conducting a microscopic examination of one of the walls under the glare of a portable light, they both saw not handwriting, as they expected, but what they believed to be badly faded abstract figures — something they never would have noticed as casual observers.

“I was looking at it, and I said, ‘This just isn’t right,’” Blackburn said. “Then Moriah spotted another one above it, and we realized we were not looking at the same thing.”

Blackburn understood immediately the discovery was on questionable scientific ground, as rock art had never been thought to be part of the history of the site. He also realized the figures were so faint that many observers likely would dismiss them as nonexistent.

“Some people see it immediately, other people don’t see it at all,” he said.

Over the course of its surveys, the team would come to identify 300 such renderings. Blackburn took to calling them ancient Puebloan stealth art, as the renderings were described by his friend Winston Hurst, an archaeologist brought in by Blackburn to examine them.

The renderings were created through three techniques, Blackburn said he believes — incising, painting and stippling, a process by which an image is created by an artist using small dots or specks.

As Blackburn writes in chapter four, his team then brought in archaeologist and rock imagery expert Larry Loendorf to provide an initial assessment of those findings. Blackburn said Loendorf chosen to focus on the painted elements, with pigments “as they were most clearly not EuroAmerican and had the possibility of being dated.”

Blackburn said Loendorf was intrigued by the findings, and discussions ensued about the possibility of his leading a team to come back to Aztec Ruins to do more detailed work on the renderings. That work would include the use of a program to digitally enhance some of the images to gain a better understanding of their nature.

While the renderings have not been officially recognized, Blackburn maintained they could not be random.

“What convinced me was the intentional incise placement before they stippled,” he said, describing the techniques used by the artists. “It was planned, down to the stones they brought in to do it.”

Blackburn said he welcomes a rigorous scientific examination of his team’s findings and conclusions, believing they will hold up under scrutiny.

“That’s part of science,” he said of those who might cast doubt on the discovery. “The doubters are good because then you can go into the whole thing, and they’ll have to disprove it. What I didn’t want to happen was for the park to cover it over.”

He said he’s prepared to defend his position that the renderings are what he believes they are.

“There are going to be a lot of doubters, people who say, ‘Well, you’re just making this up,’ like it’s some kind of Anasazi Rorschach kind of thing,” Blackburn said. “But there’s been documented abstract art found at other ruins.”

The work continues

What began as a one-year project has turned into something that Blackburn said he likely will spend the rest of his life working on, at least part time. In addition to the pioneering discoveries his team made, he said, the greatest contribution he and his surveyors made is the development of a sound road map to guide further exploration of historic inscriptions in rooms at Aztec Ruins, as well as at other locations.

That, he said, was the most enjoyable part of the experience for him.

“Our methodology will undoubtedly require some adjustments in the future but we feel that the big part of the learning curve is complete,” he wrote in the report’s final chapter, recommending that an additional eight rooms in Aztec West and an unknown number of rooms in Aztec East be surveyed.

Those interested in learning more about the project will have a couple of opportunities to hear Blackburn discuss the team’s work in the months ahead. He will deliver a presentation at 1 p.m. on Saturday, Aug. 26 at the Animas Museum, 3065 W. 2nd Ave. in Durango, Colorado, and another one at 6 p.m. Wednesday, Nov. 15 at the Farmington Civic Center, 200 W. Arrington St.

Blackburn said he already is pondering who might assume his role of leading additional surveys at the ruins should additional funding for that purpose become available. But for now, he is allowing himself the luxury of feeling a sense of satisfaction over his role in contributing a significant new chapter or two to the history of Aztec Ruins.

“I don’t know how I got started in all this, but I’m sure lucky to have done it,” he said.

In the preface she wrote for the report, his wife, Atkins, puts the experience she shared with Blackburn and others in further perspective.

“Undeniably, the main story of the Aztec West great house focuses on the Pueblo people who built it and flourished here in the 11th and 12th centuries, and their descendant families,” she writes. “Aztec West lives on, not as a dead ruin stuck in time, but with a continuing spectrum of stories to be shared of timeless farmers, children, neighbors, and visitors.”

Mike Easterling can be reached at 505-564-4610 or measterling@daily-times.com. Support local journalism with a digital subscription: http://bit.ly/2I6TU0e.

This article originally appeared on Farmington Daily Times: Aztec Ruins historical inscriptions survey team issues 270-page report