Azzi: Bending the arc to embrace the promise of justice

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This week, an arc bent toward justice in Boston Common, where a 20-foot tall bronze sculpture was unveiled to honor The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., his early life in Boston, and his all-too-short life spent confronting injustice.

"The Embrace," conceived by artist Hank Willis Thomas and inspired by a photograph, symbolizes the hug Dr. King and Coretta Scott King - who had met while King attended Boston University and Scott King attended the New England Conservatory of Music - exchanged after MLK was awarded the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize.

“In that photograph of them in 1964," the artist explains, "his arms are wrapped around her but also his weight is on her. To see her so gracefully and lovingly carrying that weight, it was a metaphor for what she was able to do throughout a huge portion of my life.”

That may all be true - but it's not enough for me. Although it's an extraordinary artwork, intimate in concept, affectionate in expression, it fails, in my mind, to elevate the fullness of a prophetic witness who dwelled and perished - on our behalf at great personal risk to himself and his family - at the intersection of love, race, religion, politics, and social change.

Boston had a chance to get it right - and I think they failed. The Embrace is too personal, too disembodied, too intellectual. It falls too short of what MLK represents to America.

My MLK was a radical, a revolutionary, a man who on the day he was assassinated, April 4, 1968, called his mother to give her his next Sunday’s sermon title: “Why America May Go to Hell,” that he was to warn that “America is going to hell if we don’t use her vast resources to end poverty and make it possible for all of God’s children to have the basic necessities of life.”

My MLK was an unreconstructed patriot, an imperfect yet courageous and compassionate American whose legacy is today in danger of being whitewashed by individuals and institutions once willing to accept his "Dream" but unwilling to embrace the reality of his vision that threatened their privilege and power.

As King became more confrontational, as he defined the intersectionality of revolutionary movements in both America and abroad he became more 'unacceptable' to White America.

King, who believed that “Colonialism and segregation are nearly synonymous . . . because their common end is economic exploitation, political domination, and the debasing of human personality” was by 1967 preaching “I’m not only going to be concerned about justice for Negroes in the United States because I know that justice is indivisible, and injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. I’m concerned about justice for everybody the world over.”

Indeed, King, who at the time of his assassination was in Memphis in support of a strike by sanitation workers, understood that resisting oppression and exploitation, poverty, and injustice were human rights, not just Black rights.

That was unacceptable to many Americans, particularly to white Americans enmeshed still in a white supremacist vision of a nation built by enslaved labor on land acquired by genocide and theft.

As African-American demands for justice and equality accelerated, King’s ideas and activism made him increasingly unpopular. While just 39 percent of Americans disapproved of MLK in 1964, the year he became a Nobel Laureate, by 1966, 63 percent of Americans viewed him unfavorably.

Today, MLK is increasingly viewed through a revisionist lens meant to make white people more comfortable with their own complicity in systems of white supremacy. In an America uncomfortable with “peaceful protests,” non-violent resistance, sit-ins and boycotts, King was romanticized by many white Americans as a 'good' Black American in contrast to Malcolm X, Angela Davis, Medgar Evers, Rosa Parks, Fred Hampton, Muhammad Ali, Tommy Smith and John Carlos, and others seen as being too confrontational and disruptive by white Americans.

That was the America that assassinated MLK, an America that believed Black Americans didn't know their place.

On April 4, 1967, one year before he was assassinated, Dr King preached at Riverside Church in New York City: "Beyond Vietnam - A Time to Break Silence:"

"Over the past two years, as I have moved to break the betrayal of my own silences and to speak from the burnings of my own heart, as I have called for radical departures from the destruction of Vietnam, many persons have questioned me about the wisdom of my path. At the heart of their concerns this query has often loomed large and loud: 'Why are you speaking about the war, Dr. King?' 'Why are you joining the voices of dissent?' 'Peace and civil rights don't mix,' they say. 'Aren't you hurting the cause of your people,' they ask? And when I hear them ... I am nevertheless greatly saddened, for such questions mean that the inquirers have not really known me, my commitment or my calling. Indeed, their questions suggest that they do not know the world in which they live.

That is my MLK, a full-throated, unrepentant American fighting for a belief that all peoples are created equal - and that got him killed.

I want Americans to know that MLK.

Then, only then, will they come to understand how much further the arc must bend to fulfill the promise of The Embrace in Boston Common.

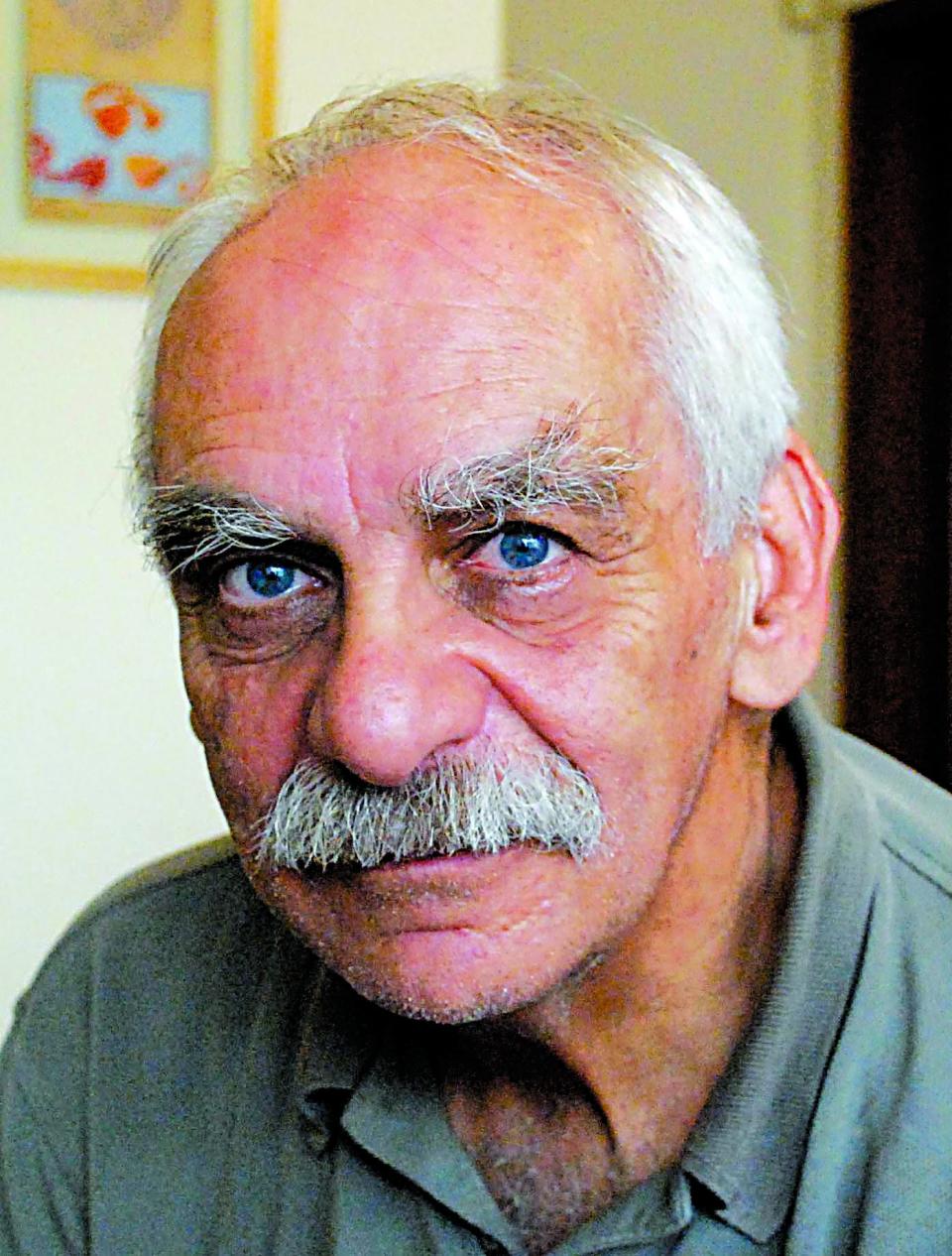

Robert Azzi, a photographer and writer who lives in Exeter, can be reached at theother.azzi@gmail.com. His columns are archived at theotherazzi.wordpress.com.

This article originally appeared on Portsmouth Herald: Azzi: Bending the arc to embrace the promise of justice