Azzi: Bill Russell's life on and off the court will long continue to inspire

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Medgar Evers was assassinated on June 12, 1963 in Jackson, Mississippi; murdered by a white segregationist KKK and Citizens' Council member who hated Blacks, Jews and Roman Catholics.

Evers, a WWII Army veteran, was the NAACP’s first Mississippi field secretary and worked to organize voter-registration drives and economic boycotts; activities resented and resisted by much of Mississippi's white segregation-favoring population.

Evers, murdered in his driveway, was immediately succeeded by his brother, Charles, who had worked alongside Medgar organizing NAACP activities.

Upon learning of the assassination, Boston Celtics superstar Bill Russell called Charles and asked what he could do.

"Get down here,” Evers replied, “and we'll open one of the playgrounds and we'll have the first integrated basketball camp in Mississippi.”

Russell did exactly that: Fewer than two months after the Celtics had beaten the Los Angeles Lakers to win their sixth NBA championship under Russell's leadership, he traveled to the Deep South to support Charles, support civil rights for all Americans.

He did it because he knew that is what we're called upon to do.

Mississippi in the early '60s was a dangerous place. From the 1961 arrests of over 300 Freedom Riders in Jackson alone, to Citizens' Councils, to riots over James Meredith's attempt to enroll at the University of Mississippi — to murders, bombings and intimidation — violence against Black Mississippians and supporters was common.

Yet, at a time when his greatness as a basketball star was reaching its zenith, at a time when civil rights work in the South was fraught with danger, Russell traveled to Jackson and set up an integrated camp; an activity deemed so dangerous that at night — as Russell slept in a bed too short for his 6-foot-9-inch frame — Charles Evers sat up in a chair and guarded Russell's motel room with a rifle.

"Let my people go, oppressed so hard they could not stand, Let my people go."

Regretfully, I never got to see Bill Russell play in person. I got to know him listening to play-by-play broadcasts by Johnny Most, sometimes on a small transistor radio under bedcovers on school nights when I should have been sleeping.

I didn't know till later that Boston wasn't a welcoming place for players of color; that it was particularly hostile to players who might be too "uppity," players not sufficiently deferential to "white sensitivities."

I didn't know till later that in spite of raising the quality of Celtics basketball to previously unrealized heights just how much Russell's presence in Boston was scarred by racism and white resentments.

What I do know is that in the end he triumphed over those who vandalized his house and defecated on his bed. He triumphed over those who rained down racist epithets from seats in the Boston Garden, triumphed over those who called his team the "Boston Globetrotters" because of its inclusion of players of color.

Triumphed over the racism of the FBI who kept a file on Russell, describing him as “an arrogant Negro who won’t sign autographs for white children.”

Under such abuse it would have been easy for Russell to have become just another gifted athlete — flaunting more championship rings than he had fingers for — celebrated for his talent and winning ways.

That just wasn't Bill Russell.

Since his death last Sunday we've been gifted with reminiscences of Russell the athlete who won an Olympics gold medal, two NCAA championships, 11 NBA championships (two as player-coach) and one Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Reminiscences of Russell the activist who stood for respect, human dignity, and equality; the activist who at age 83 lowered himself to one knee and tweeted: “Proud to take a knee and to stand tall against social injustice.”

For me, Russell was a charismatic presence halo'ed in baraka, an Arabic term that often refers to leaders who radiate an almost ineffable holiness, a spiritual force; who have been gifted to humankind to remind us of the beauty and grace of the Beloved; who remind us that from those upon whom special gifts have been bestowed much is expected.

Russell reminded us that we must come to know one another.

Fewer than three months after he mourned Medgar Evers, on Aug. 28, 1963, Russell went to Washington to join the Rev. Dr, Martin Luther King Jr. and the March on Washington.

On June 4, 1967, fewer than two months after losing the Eastern Division finals to the Philadelphia 76ers, Russell joined Jim Brown, Carl Stokes, Kareem Abdul Jabbar (then Lew Alcindor) and others — at what is today called the Cleveland Summit — to support heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali, who was refusing to serve in Vietnam.

NBA superstar Charles Barkley tells of Russell once calling him to tell him to stop complaining about paying high taxes:

"Be happy you're making a lot of money and they can tax you a lot ..." Russell scolded him. "There was a time you were poor, when the cops came to your neighborhood, when you went to public school, somebody else was paying those taxes, too."

Barkley says he never complained about his taxes again.

Bill Russell was born in Louisiana in 1934. In 1942, during the Great Migration, when millions of African-Americans fled the South in search of a better life, his family moved to Oakland, California.

Russell died last Sunday at his home on Mercer Island, Washington, and since then I have read innumerable reminiscences and recollections about a most extraordinary and triumphant life of grace and beauty.

An extraordinary and triumphant life defined by doing the right thing.

“Bill Russell was the quintessential big man," Kareem Abdul Jabbar tweeted. "Not because of his height but because of the size of his heart.”

"Glory, Glory, Hallelujah. His soul goes marching on."

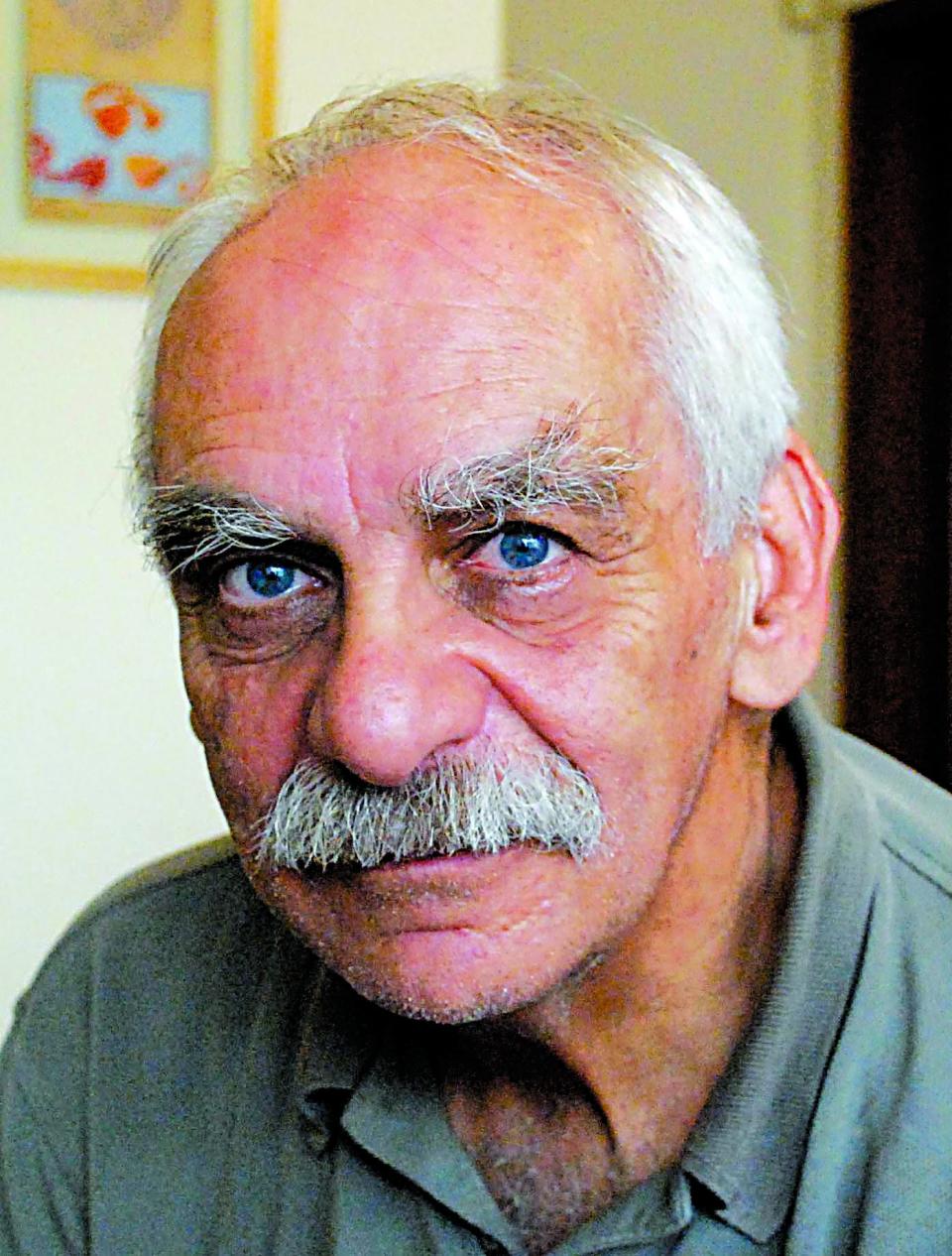

Robert Azzi, a photographer and writer who lives in Exeter, can be reached at theother.azzi@gmail.com. His columns are archived at theotherazzi.wordpress.com.

This article originally appeared on Portsmouth Herald: Bill Russell's life on and off the court continues to inspire