Azzi: Salman Rushdie: We are made up of bits and fragments

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

I am ready to resume reading in public again.

Banned Books Week in America, promoted by the American Library Association and Amnesty International "in shared support of the freedom to seek and to express ideas, even those some consider unorthodox or unpopular," is held annually during the last week in September.

In pre-pandemic days I would support that work by volunteering to read at events held in bookstores or public libraries.

Today, more than ever, that support needs to be affirmed and expressed.

I'm ready.

I often read from Salman Rushdie's "The Satanic Verses," making sure to include passages that some Muslims condemned as blasphemous.

Generally, those passages referred to a figure named Mahound, whom critics wrongly regarded as a blasphemous representation of Prophet Mohammed. Mahound appears in the book only as a character in another character's dreams, the delusions of Gibreel Farishta, a character who believes he's archangel Gabriel and who is later diagnosed as mentally ill.

In Gibreel's dreams, Mahound is a businessman struggling with issues of identity and belonging turned prophet trying to save Jahilia, a city famous for gambling dens and whorehouses, from its corruption.

"The city of Jahilia is built entirely of sand, its structures formed of the desert whence it rises. It is a sight to wonder at: walled, four-gated, the whole of it a miracle worked by its citizens, who have learned the trick of transforming the fine white dune-sand of those forsaken parts, - the very stuff of inconstancy ... and have turned it, by alchemy, into the fabric of their newly invented permanence."

Such words as those were penned by a gifted writer, born in Bombay to a Muslim family, who now lives in New York City. In 1989, his novel, "The Satanic Verses," earned Rushdie a death sentence from Iran's Ayatollah Khomeini for allegedly being ant-Islamic and insulting to Islam's prophet, Muhammad.

Last week Khomeini's death sentence incited a religious fanatic to try and murder Rushdie. Thankfully, Salman Rushdie survived the assault and his assailant was arrested.

I have read "The Satanic Verses" twice and, as I understand it, despite its dependence on early historical narratives in the history of Islam, it is neither blasphemous nor anti-Islam.

But that's besides the point.

The point is that even it it were blasphemous and anti-Islam or anti any religion or institution or government, the author has an inalienable right - unfettered by societal, religious, government, or interest group conventions - to create it and get it published.

An inviolable right, affirmed by the words of German-Jewish poet Heinrich Heine:

"Das war ein Vorspiel nur; dort wo man Bücher verbrennt, verbrennt man auch am Ende Menschen: That was merely a prelude; where they burn books, they end up by burning people."

When I was last in Berlin, Germany I read those lines - written in 1823 by Heine - inscribed on a plaque in the Bebelplatz where an empty, underground library memorializes the public burning of 20,000 books on May 10, 1933 in many university cities across the Reich by Nazis to "purify" and "cleanse" German literature and culture. Among the books torched were works by Heinrich Mann, Erich Maria Remarque, Heinrich Heine, Karl Marx, and Albert Einstein.

“History has taught you nothing if you think you can kill ideas ..." Helen Keller, whose books were also burned, responded: "... You can burn my books and the books of the best minds in Europe, but the ideas in them have seeped through a million channels and will continue to quicken other minds.”

I believe that even blasphemous works must be protected, protected even when they make us uncomfortable, protected even when free speech is used to punch down upon disenfranchised and marginalized peoples who have no media platforms upon which they can respond.

Today, the discussion over the attempted assassination of Salman Rushdie at Chautauqua is also a reminder that America itself is increasingly limiting itself as a sanctuary for free expression and a forum for the free exchange of ideas - especially for unorthodox or unpopular ones.

Today, just as Rushdie's Muslim critics ignored the dream sequences and were unable to enter into his metaphors and parables, we are confronted by American ayatollahs unable, unwilling to understand and accept the aspirational values of our constitutional republic.

Unable to accept that all Americans are created equal.

Today, the intimidation of artists and ideas in America is more sophisticated than death-fatwas, assassinations, and book burnings.

It comes by using public funds to support religious institutions, by refusing equitable access to resources and opportunities.

We are witnessing a pernicious push to cleanse America of its pluralistic roots, to resist multiculturalism, to refuse the sojourner.

We are witnessing the racist embrace of replacement theory and the ignorant denunciation of Critical Race Theory, witnessing attempts to impose a caste system on communities of color.

We are witnessing Khomeini's fatwa being replaced by preachers, politicians, pundits and petty bureaucrats ignorant of their faith while certain of their ignorance purging libraries and programs of books and resource materials that don't comport with their vision of an evangelistic, white supremacist Christian nationalist homeland.

We are witnessing an America that is moving to deny the Founding Fathers' vision that a secular worldview is the best guarantor of religious freedom, that none is favored above the law.

''What is being expressed is a discomfort with a plural identity,'' Rushdie said in 1989 and remains true today. ''And what I am saying to you - and saying in the novel - is that we have got to come to terms with this. We are increasingly becoming a world of migrants, made up of bits and fragments from here, there. We are here. And we have never really left anywhere we have been.''

We are made up of bits and fragments.

We are here.

There is a story of a woman who lived in Medina during the formative days of the Muslim community in Arabia.

Daily, as the Prophet Muhammad walked past her house, she would throw trash on him.

The Prophet never responded or retaliated.

One day, when the woman didn’t appear and there was no one to throw trash on him, the Prophet went to her home to visit her, to inquire and see if she was well.

Who, I wonder, will knock on our door?

Who, I wonder, will ask if we are well?

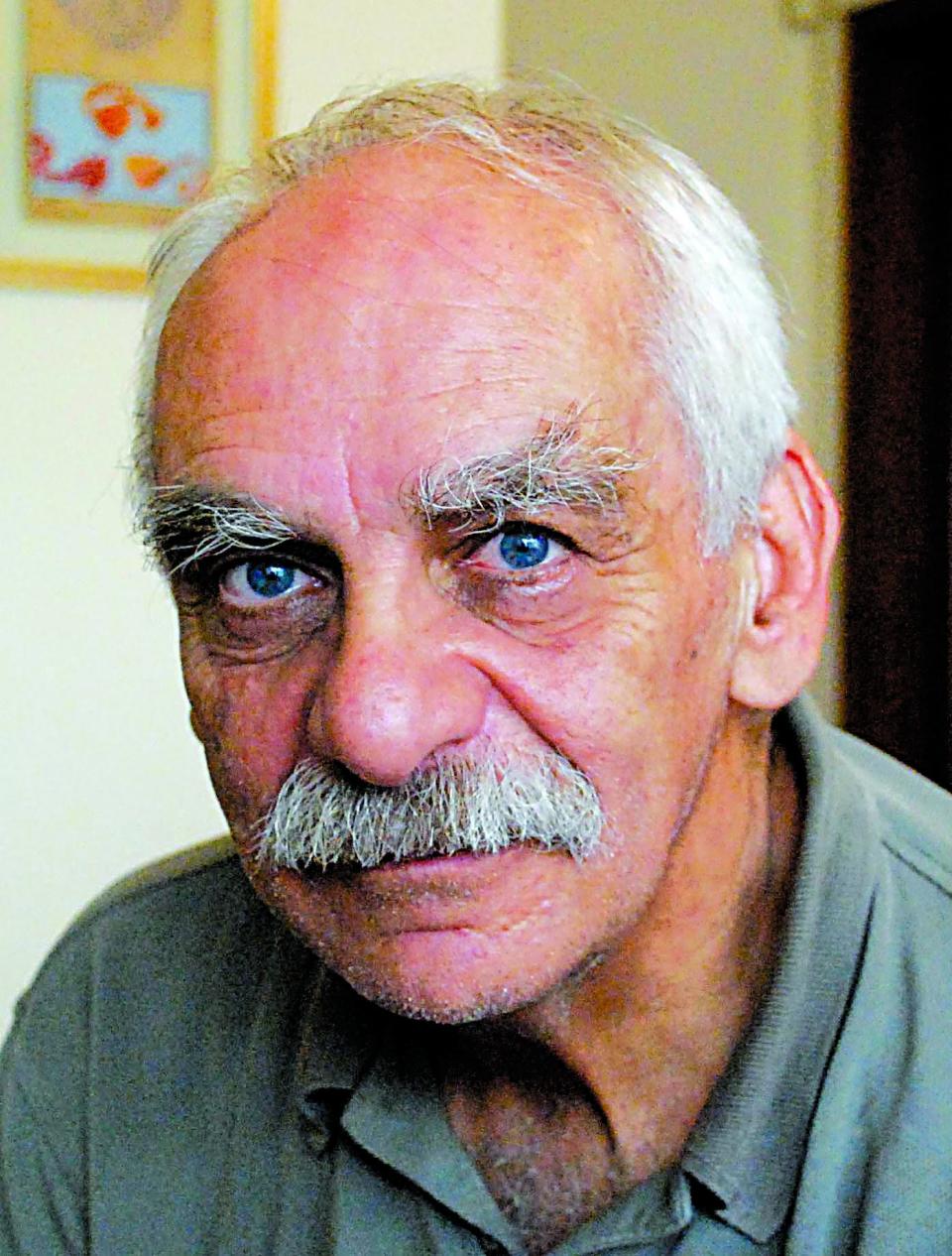

Robert Azzi, a photographer and writer who lives in Exeter, can be reached at theother.azzi@gmail.com. His columns are archived at theotherazzi.wordpress.com.

This article originally appeared on Portsmouth Herald: Azzi: Salman Rushdie: We are made up of bits and fragments