B-spec Honda Fit vs. Kia Rio5, Mazda 2, Mini Cooper Hatchback

On the list of mankind’s vital pursuits, racing ranks with procreation, fine dining, and the consumption of refreshing beverages. Speed is fundamental to any human’s spiritual well-being. So, when the Sports Car Club of America (SCCA) tempted us with a new easy-entry B-Spec road-racing category, primal urges drove us to find out which of the four cars gathered here offers the quickest path to enlightenment.

We’ve trod this road before. Forty years ago, when the SCCA invented Showroom Stock sedan racing, Car and Driver took the bait. Within seven years, two editors had ascended the speed ladder to compete at the 24 Hours of Daytona. Patrick Bedard, C/D’s quickest shoe, accelerated from squalling econoboxes to Indy cars in a decade.

Like everything, Showroom Stock benefits from an occasional pick-me-up. Two years ago, Mazda’s director of motorsports, John Doonan, and Honda’s production racing authority, Lee Niffenegger (an engineer and two-time SCCA champion), met at a trade show to brainstorm ways of making entry-level classes more enticing. Niffenegger envied Mazda’s status as the king of amateur road racing. Doonan smelled fresh blood.

Discussions focused on the smallest, cheapest cars in each brand’s portfolio: the B-size Honda Fit and Mazda 2. Both were fun to drive and loaded with racing potential. Honda and Mazda exercised care to avoid past pitfalls—the tendency for Showroom Stockers to go stale after a few years and the uneven-playing-field syndrom, wherein the alpha models hog all the glory.

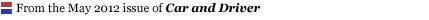

The B-Spec class that emerged resides in the middle ground between the SCCA’s Showroom Stock category, where nearly no modifications are allowed, and its faster Touring classes where various engine and chassis alterations are permitted. Tinkering is encouraged, but no hard-core fabrication (beyond constructing a full roll cage) is necessary. Those on a tight budget can reach back to previous model years as their B-Spec starting point.

A high degree of portability was core to the B-Spec plan. To assure that one set of rules could play at several sanctioning bodies, interested carmakers maintained an open dialogue and limited the performance-enhancing changes to chassis areas (wheels, tires, brakes, suspension—see sidebar). To fix the weight-to-power ratio at roughly 23 pounds per pony across the board, consulting engineer Kevin Fandozzi determined an appropriate race-ready weight and intake restriction for every eligible car. A test of four cars driven by several drivers at a Michigan track and on a portable dynamometer confirmed that Fandozzi’s recommendations were in the ballpark.

Two B-Spec cars made their track debuts in 2010 at the National Auto Sport Association’s 25 Hours of Thunderhill event. This year, they’re eligible to compete in nine support races held during three SCCA Pro Racing Pirelli World Challenge weekends and in six races run in conjunction with Grand-Am events. The SCCA currently grids B-Spec cars with Showroom Stock C (SSC) racers; when their numbers rise, the club is likely to grant this category its own class. A total of nine cars are eligible so far. In addition to the Honda Fit, Kia Rio5, Mazda 2, and Mini Cooper tested here, the B-Spec category is also open to the Chevy Sonic, Fiat 500, Ford Fiesta, Nissan Versa, and Toyota Yaris; our call to compete found none of those models ready to race.

In January, Voytek Burdzy of Schiller Park, Illinois, recorded the first SCCA B-Spec finish by driving his Mazda 2 to third overall in a field of four SSC cars at a Sebring national race. That set the stage for our acid test: lapping Mazda Raceway Laguna Seca flat-out for a day to expose the category’s highs and lows. Four C/D editors strapped in to buzz four Bs. Following tech inspection, we recorded extensive cornering, braking, and accelerating data to help prospective competitors place their bets on a car to take racing.

The first discovery was that none of the cars mustered for this test complied with the letter of the rules. Every car but the Mazda 2 was a touch lower than allowed. Intake restrictors installed in the Fit and the Rio were too large. The Mini Cooper was equipped with adjustable shocks (which we didn’t adjust), and the Rio was more than 100 pounds underweight.

Our second revelation was that each prep kit did a fine job of converting a fun but floppy road car into a track demon. None of these cars tipped, dived, or wobbled when spurred to their impressively high limits. The most egregious mechanical foible was one loose wheel. All of the cars we tested will entertain drivers of widely varying skill levels. A week after the dust settled, our necks still ached from the sustained g-load punishment inflicted by these Bs. What they lack in chest-thumping power, this foursome makes up in tenacious grip, thanks to astute suspension calibrations and the sticky BFGoodrich g-Force R1 “street legal” slicks fitted to each car.

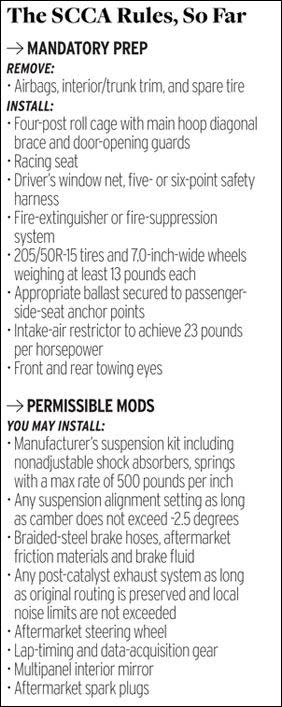

Thanks to Niffenegger’s nurturing—specifically his development of Honda Racing’s $2800 suspension, brake, and exhaust component kit—what began life as a phone booth evolved into a super subcompact without any involvement from Clark Kent.

The Fit’s tall build, low beltline, and panoramic windows enable easy sighting of critical braking, turn-in, and apex points. Spotting the exact location of enemy pursuers will also prove useful in the heat of B-Spec battle.

The Honda earned high praise for its good basic balance, willingness to turn, and poise at the ragged edges of adhesion. Trail braking swings its tail nicely. In left turning, the Fit tied with the Mazda 2 at the head of the class with 1.16 g. Steering and braking systems both provide useful feedback while the shifter and pedals are nicely arranged for heel-and-toe operation. Several drivers rated the Fit the easiest of the four cars to drive at the limit.

Compensating for its stock-trim power and torque deficiencies, this Honda has a ravenous appetite for rpm. That helps overcome gearing issues—third is short for some of the flat-out bends while fourth feels gutless—and the difficulty in reading the tach, which is buried in a deeply recessed, shadowy instrument cluster. To its credit, this car hit 95.0 mph at the end of the straight, the highest velocity recorded all day.

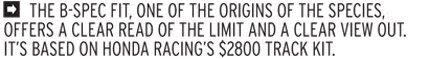

Compared with the Fit’s bright cabin, the Rio5’s is borderline claustrophobic, the result of its thick pillars and closed-in conning tower. Other issues are slow, nonlinear steering; a brake pedal that’s mushy and uncommunicative; and an imprecise shifter that places excessive demands on the driver’s concentration.

While that sounds damning, we had little difficulty driving around these concerns to post this test’s fastest laps. The Rio was not only the quickest by a full second at Mazda Raceway, it also topped the field in braking (0.93 g before entering the start-finish straight) and in high-speed cornering through the intimidating Turn Nine (a 75.8-mph bend we dubbed “Braveheart”). Understeer evident during turn-in melts away in sustained high-speed sweepers and when using trail braking to pirouette this car into slow corners. Climbing the grade between Turns Five and Six, the Rio logged a speed increase of 16.3 mph, topping its closest rival by nearly 3 mph.

Most of this performance advantage is attributable to the Kia’s two deviations from B-Spec requirements. It ran light during our test and was fitted with a 32-mm restrictor instead of the 23-mm blowhole the SCCA mandates. According to Matt Mason of Kinetic Motorsports, Kia’s racing partner and the shop that constructed this car, the engine bucked in angry protest when its airflow was choked down to the legal limit, so there was no point showing up with that configuration. Since the Kia’s engine sensors won’t tolerate the 23-mm restrictor, negotiations between Kia and the SCCA are under way to find an alternative means of diminishing the Rio’s 138 horsepower. Kinetic hopes that the current 2600-pound minimum-weight specification won’t be changed. Reaching that spec would have meant adding 100 to 130 pounds to our test car.

No stranger to building serious Kia race cars, Kinetic went all out on this project. The OMP racing seat installed here earned raves, and the AiM MXL instrument cluster’s flashing LEDs proved vastly superior to any stock tach for exploiting every last rpm. Kinetic’s prep kit, expensive at $14,000, is a soup-to-nuts package that includes roll-cage tubes, a fire system, a steering wheel with mounting hardware, the racing seat, restraint systems, springs, shock absorbers, brake pads, wheels, tires, and the parts needed to add a quart of oil capacity for enhanced reliability. Kinetic installed “turbo” and “NO2” toggle switches in the dash as comic relief; they’re not included in its prep kit.

This Mazda warrior is a B-Spec veteran with 25 Hours of Thunderhill racing under its belt and a decent mix of power, handling, and braking virtues. Don’t read too much into the 2’s fourth-place grid position because its best lap was but a tenth or two behind the Honda and the Mini. Even though this is another tall boy, body motion is nicely restrained and handling is balanced. Hints of lift-throttle oversteer are easily controlled.

In the tight Andretti Hairpin (Turn Two), the Mazda scored 1.16 g, tying with the Fit’s top-dog performance. While the 2 was the slowest car at several of our measuring points, it was also the quickest through the last turn and onto the start-finish straight; that should yield a distinct passing advantage during any race at this track.

The most notable Mazda 2 fault was a touch of instability when the ABS kicked in during hard braking. The pedal is sensitive and easy to modulate, but the front end hunts for a moment when diving into slow corners. While the tach is difficult to read, the rev limiter’s action is so gentle that shifting by ear works fine. Thankfully, this car has a shift linkage you can depend on. Last, the Mazda 2’s combination of reasonable base price and $2600 prep kit makes it this test’s most affordable point of entry.

This car was constructed at the Charleston, South Carolina, Mini dealership by general manager Brad Davis for his son Robbie’s B-Spec racing campaign and used as the guinea pig for a $6100 prep kit. Even though both of the Davis drivers are of average stature, the driver’s seat was mounted as low as possible to drop the car’s center of gravity. To improve forward sightlines without the use of seat padding, we removed the Mini’s windshield wipers before lapping.

The Mini Cooper had what most of us considered the best steering—quick to respond, laced with feedback, consistently linear. “This steering feel will win races,” raved technical editor K.C. Colwell. In fact, the link to the front tires was so direct that our quicker drivers could sense the grip beginning to fade after several fast laps. Front adhesion was quickly restored via a cool-down lap or two.

In the flat-out-right Turn Four, the Mini topped the field with its brain-bending 1.26 g of grip. It was the quickest ride through the Corkscrew and the second-best B-Spec car when braking for the turn onto the start-finish straight.

Mini gearing is such that second gear is used just as often as fourth at this track. Unfortunately, we occasionally snagged the entrance to the reverse gate while easing the shifter back during the third-to-second downshift. Exercise care or concoct a lock-out to help guide your gearchanges.

This is where we’d love to send you on your way with our pick of the B-Spec litter. Given the close finish registered by three of the cars—and the likelihood of the quicker Kia slowing down once it’s burdened with appropriate ballast—picking a winner based purely on lap times is not possible. These vehicles have turned the corner from road cars to track weapons, and all four provide such an agreeable mix of entertainment and speed that we’d enjoy racing any one of them. But our goal was to guide you to one true winner, so we concocted a ballot with each of our four test drivers allowed two votes: one with price considered, one without. The Honda Fit and the Mazda 2 each earned three votes, the Mini Cooper received two, and the Kia Rio5 was no one’s pick.

To break the tie, we’re hanging victory laurels on the Mazda 2. Its combination of competitive speed and affordable price does the best job of exemplifying the B-Spec spirit. The dollars saved buying and prepping this car can go toward the case of fine champagne you’ll need to toast your racing success with friends.

You Might Also Like