The Babe's special order and Ted Williams' returns: Dive into Slugger's private records

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

America’s favorite pastime is full of historic stats and records, but as I stared down at the fragile leather ledger, I saw a completely different type of baseball record.

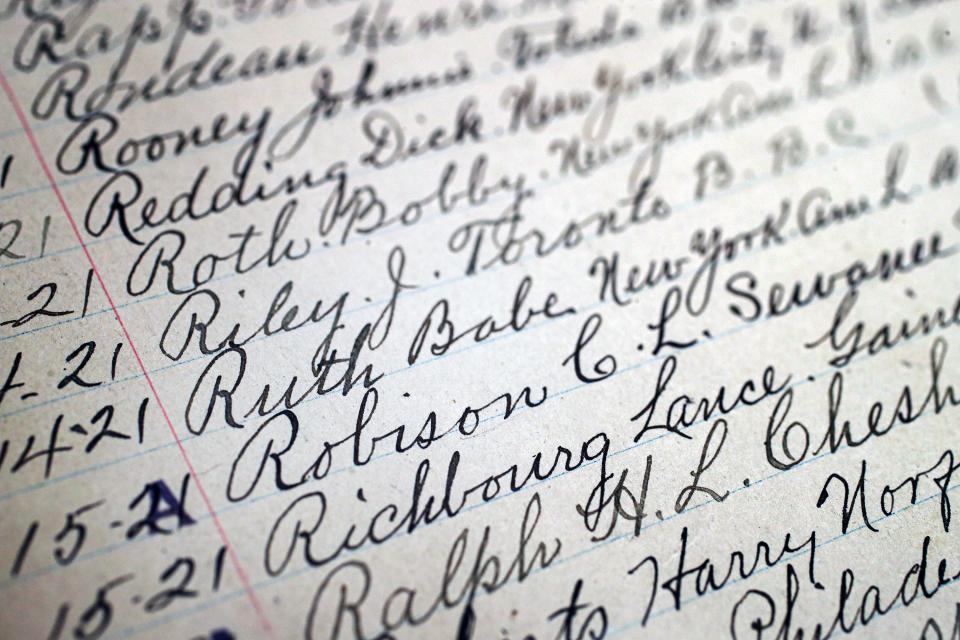

Whoever the bookkeeper was at Louisville's Hillerich & Bradsby Co. on March 14, 1921, couldn’t have known that a century later, I’d be standing in the company’s modern offices ogling at the name "Babe Ruth" written in careful, early 20th-century script. The Great Bambino requested “his model” of a baseball bat, certainly unaware that one of the three bats he designed would end up being the inspiration for the 120-foot replica planted outside what’s now the Louisville Slugger Factory and Museum at 800 W. Main St. in downtown Louisville.

A little further down the same page, the clerk recorded an order from J. Riley from Toronto. Honestly, that note and names seem insignificant, until you realize a few inches over that he didn’t want just any bat model. He wanted the same one as Shoeless Joe Jackson, the famous outfielder.

If you take the tour open to the public (as I have, on more than one occasion) at the Slugger Museum, you’ll get an up close and personal look at how baseball bats are made and personalized per player. Forbes has called it “one of the greatest sports museums in the world.” But when I asked curatorial director Bailey Mazik if there was anything tucked away in the museum at which I could have a behind-the-scenes look ― I saw the company in a completely different way.

In a way, the ledgers and bat orders Mazik pulled from the museum’s vault are a uniquely Louisville time capsule for professional baseball. But there’s more to it than that. The documents show the way this celebrated business ran in downtown Louisville before technology took over, and it gives a glimpse of how the people, who worked for Hillerich & Bradsby Co. had the smallest brushes with baseball legends like Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig and Jackie Robinson.

Contracts and autographs of baseball legends

There’s something as endearing about these papers as learning to massage your very first baseball glove with shaving cream.

The nuances in them are so human.

“It’s very utilitarian, I think,” Mazik told me.

I couldn’t agree more.

The first thing to remember is that Hillerich & Bradsby Co. didn’t set out to become one of the greatest sports museums in the world when it opened as a woodworking shop in 1855. The focus was making items like bedposts and butter churns. In 1884, Bud Hillerich crafted the company’s first bat, and it took 108 years from that historical moment for the locally owned family business to morph into a museum.

In a world of lazars and scanners, the yellowing baseball bat contracts of the early 20th century are relics of simplicity. Each contract included four different lines for the player to sign their name. The customer would choose the favorite of the four signatures to use as the template for the branding plate that would eventually put their name on all the bats they purchased.

That’s not the wildest part. All of the early bat contracts in the Slugger collection have holes in them because it was likely a Louisville clerk’s job to delicately cut out those autographs from these forms.

Can you imagine holding that sliver of paper with Stan Musial, Mickey Mantle, or Ted Williams signatures? On one hand, that's the kind of tale you tell your children and grandchildren. On the other? It's just part of your job.

Baseball legend Ted Williams sends back a box of bats

Records from the earliest days of the company in the late 19th century are lost to history, Mazik explained. The leather-bound ledgers, like the one with that Babe Ruth and the Shoeless Joe Jackson entry, began in 1911. They’re organized by year first, then alphabetized by the player’s last name, and then recorded by date.

Some players designed bats to their own specifications, and others like J. Riley from Toronto opted for the tried-and-true model of another successful player. Since the 1940s, those have been tracked by an alpha-numeric code, but back in the day, they were simply named for the player.

I imagined a 1910s bookkeeper flipping through the pages, like a cook frantically searching for a beloved or forgotten recipe as I noticed the small rips and dings along the pages and spines. Again, these were utilitarian. They weren’t meant to be historical records, but that's what they’ve become.

The ledger system worked for a while, but as the bats and even baseball grew in popularity, it needed an update.

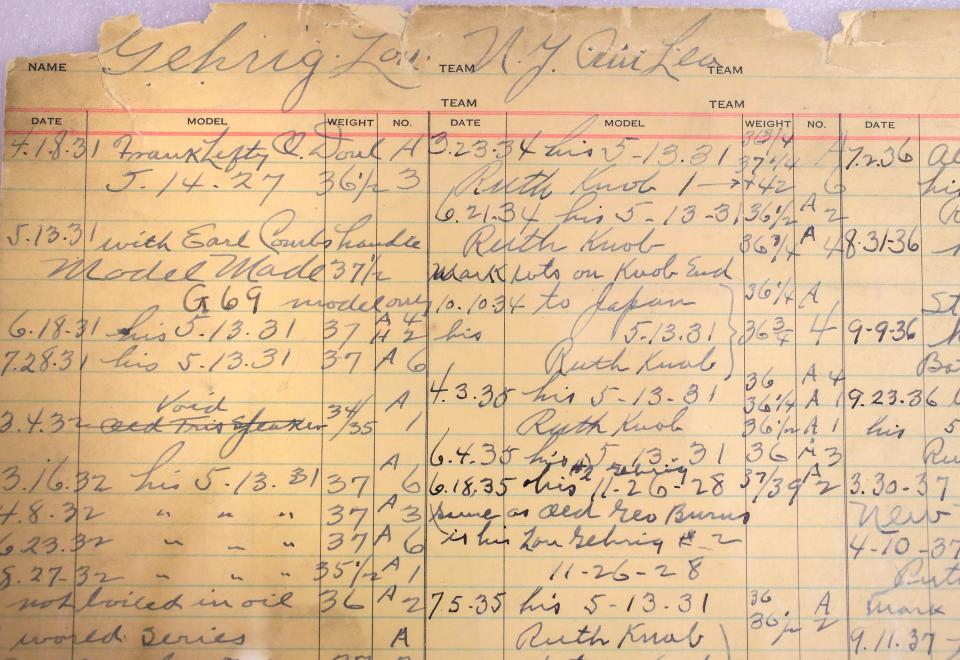

Likely some savvy and thoughtful Louisville bookkeeper introduced the card system that tracked the bats from 1930s to the 1980s. Mazik passed me Lou Gehrig’s file of laminated cards, which had the order dates and the weight of the bats on it like you’d expect to see.

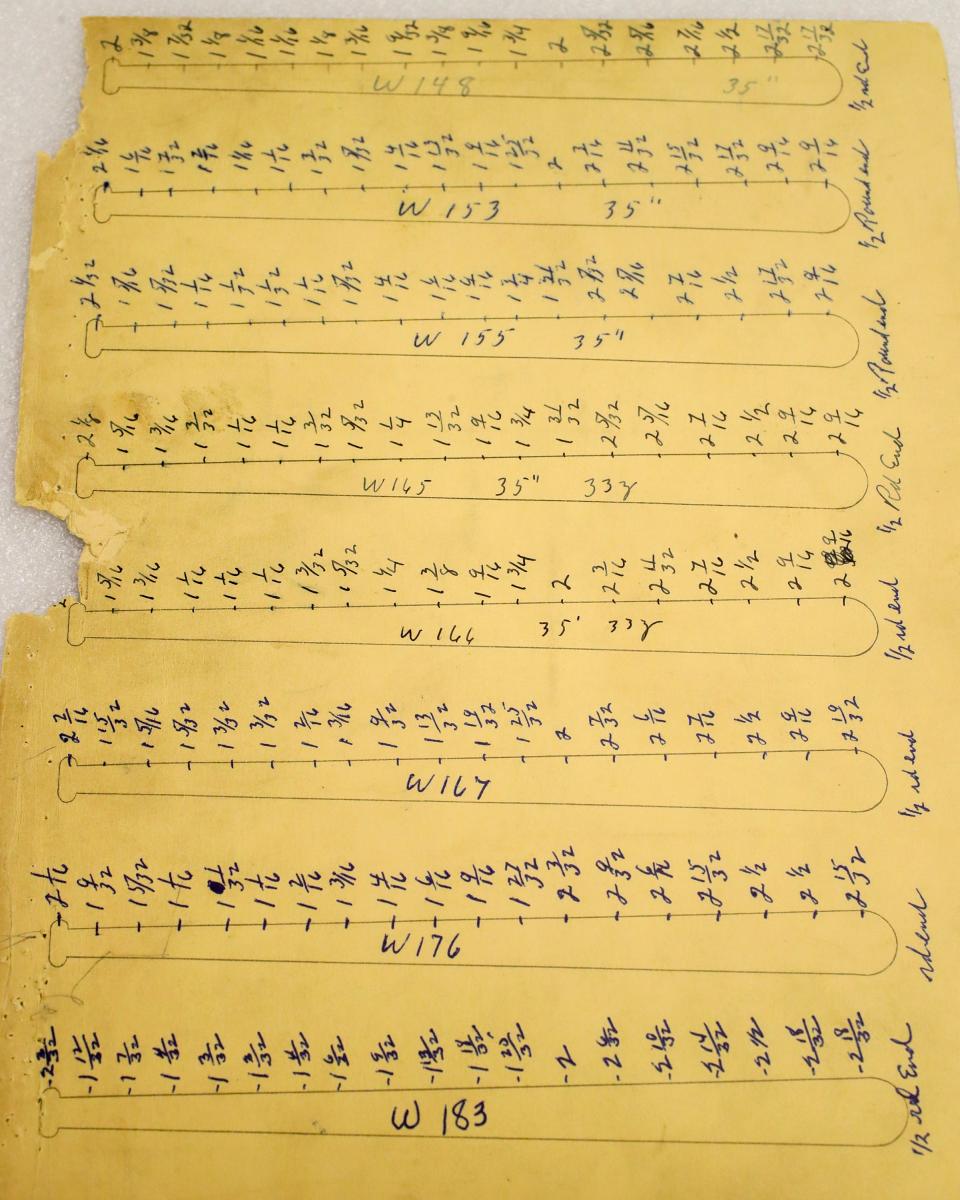

Then I flipped it over. To the untrained eye, the back looked like a page from a coloring book with eight baseball bats, but this was actually a way to track how many bat models a player designed throughout his career. From the knob to the base, there were 14 or so hand-recorded, measurements down to the 1/32nd of an inch ― which is a length so small there’s not even a line for it on a standard ruler.

As I marveled at those microscopic sizes and the detail that goes into them, Mazik told me a story about Ted Williams, who played for the Boston Red Sox in the 1940s and 1950s. He'd ordered a box of bats, and after he took the first few swings, he could tell something was off. The museum and factory's lore says when he brought them back to have them checked, they were off by the depth of a piece of paper.

And yes, the Baseball Hall of Famer could tell. The company redid the whole box.

Creating replicas of historic bats

Some players stick with one bat their entire career, and others design a dozen or so until they find one with the right fit. More often than not, the bats get heavier as a player gets deeper in their career.

There are exceptions to this, though.

A few years back, someone at the museum was looking through the order archive, Mazik said, and noticed the specs for Gehrig’s bats actually got lighter as time went on.

He played his final game in May 1939 after a dismal start from his then-mysterious neuromuscular disease. There’s no way to know for certain, of course, but it's possible favoring a lighter bat could have been an early, almost untraceable sign of his amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, more commonly known as ALS.

When you spend some time with them, it’s amazing what these order forms and ledgers can tell you.

Today they’re mostly historic records, but for decades before an Excel sheet took over for those coloring book-like cards in the 1980s, they’re what made this company tick.

But every now and then, Mazik has to go into the vault and pull one of the ledgers or cards. It's usually for a player not as popular as Babe Ruth or Lou Gehrig. Countless players in the major and minor leagues, alike, have created their perfect bat with the help of Louisville Slugger.

As an curatorial director, of course, Mazik’s job isn’t anything like the bookkeepers and clerks who made all of these records decades ago. But every now and then, the museum hears from someone looking hoping to get a replica of the bat that their great-grandpa played with.

So she goes in with gloved hands and flips through the fragile pages, or picks up those cards.

And it’s all there, in perfect detail, just as it has been for decades.

Down to the 1/32nd of an inch.

Features columnist Maggie Menderski writes about what makes Louisville, Southern Indiana and Kentucky unique, wonderful, and occasionally, a little weird. If you've got something in your family, your town or even your closet that fits that description — she wants to hear from you. Say hello at mmenderski@courier-journal.com or 502-582-4053.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: Louisville Slugger Museum baseball history: Babe Ruth, Ted Williams