Their babies died when Camp Lejeune’s water was poisoned. But justice has been hard to find

JACKSONVILLE, N.C. — The mothers did not know why their babies were dying at Camp Lejeune.

Jeri Kozobarich noticed something was wrong as soon as she arrived at the sprawling U.S. Marine Corps training facility in North Carolina, healthy and seven months pregnant, in the spring of 1969.

At a reception for the wives of the officers on the base, Kozobarich approached another pregnant woman who was “round as a ball” and dressed in black.

“When are you due?” Kozobarich asked.

“My baby is dead,” the woman said, before turning away.

Horrified, Kozobarich raced home, unable to fathom such a fate. Then, at a routine weekly checkup at the facility’s Naval hospital about two months later, she had to. A doctor told Kozobarich, who had no previous pregnancy complications, that the baby girl in her womb was dead.

Kozobarich, then 24, carried the baby for another three weeks until she delivered on May 24, 1969. Then she buried her first child in a section of a cemetery known as "Baby Heaven," tucked next to Camp Lejeune, where dozens of infant graves surround Kozobarich’s daughter's and the tiny teddy bear statue that marks her headstone.

As she and her Vietnam-bound husband grieved, Kozobarich said the unit’s commanding officer visited their home with intentions to console them. Instead, she said, he sat down on their couch and burst into tears himself.

“He sobbed,” Kozobarich recalled, “and he said, ‘Why is this happening to all of us?’”

Justice delayed

In one of the largest water contamination cases in U.S. history, up to 1 million people who lived or worked at Camp Lejeune from 1953 to 1987 may have been exposed to a drinking water supply contaminated with chemicals that have been linked to severe health problems, including cancers and birth defects, federal health officials said.

Women on the base quietly suffered repeated miscarriages, stillbirths and other defects during that time period, but many said their losses were often dismissed.

Today, as they continue seeking justice under a new law meant to expedite litigation, their cases have fallen under intense scrutiny, which has left many women, including 23 who spoke to NBC News, feeling as dismissed as they felt decades ago.

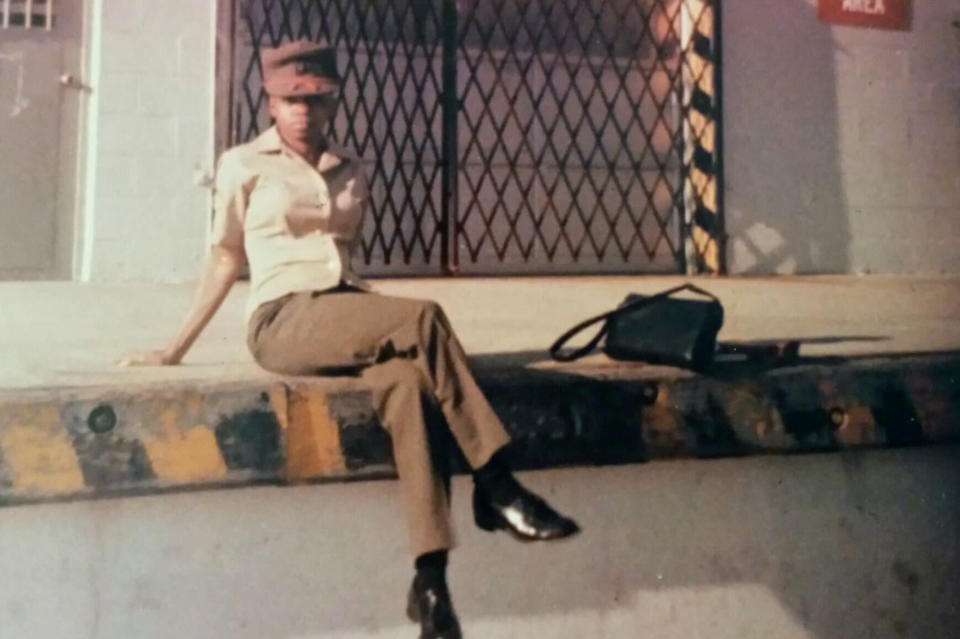

“It’s like we’re invisible,” said LaVeda Kendrix, 65, a Marine veteran, who had one stillbirth and nine miscarriages.

When the Camp Lejeune Justice Act was enacted last year, it allowed victims to pursue litigation against the government if they could prove they were at the base for at least 30 days during the contamination timeframe and that the exposure to the tainted water likely caused their health issues.

But miscarriage and female infertility cases have been uniquely difficult to litigate, according to four attorneys who represent tens of thousands of Camp Lejeune claimants.

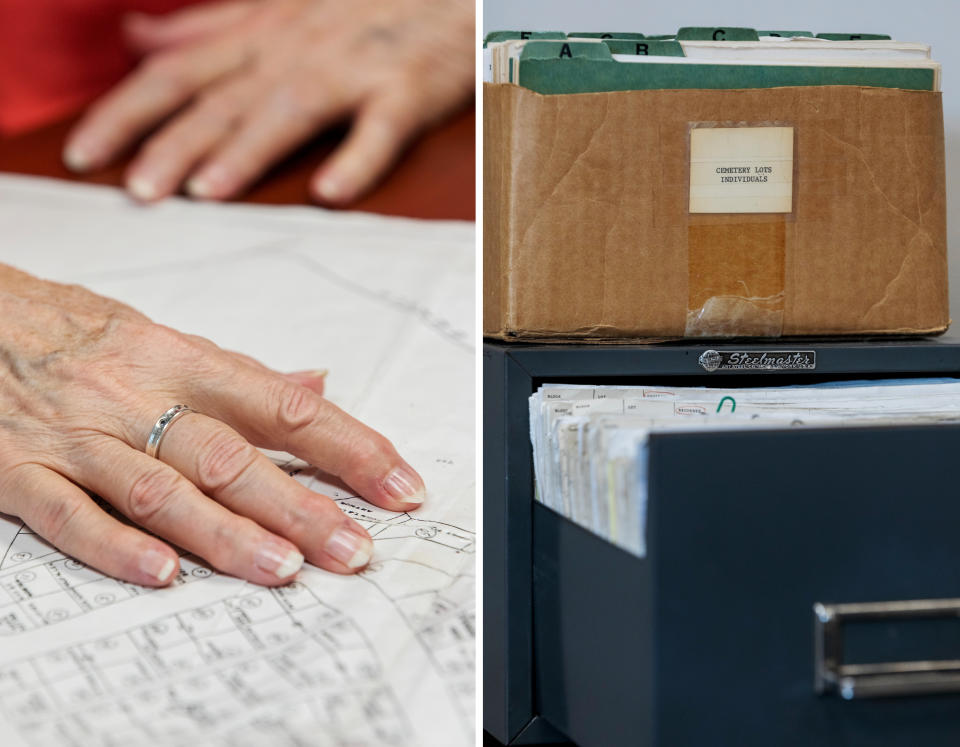

For the vast majority of all cases — particularly those related to adverse birth outcomes — it’s been challenging, and sometimes impossible, to retrieve necessary medical records to prove the arguments from so far back, the attorneys said.

“They had to wait 30, 40 years to file a claim. It wasn’t their fault that delay of time has caused the absence of records,” said Ed Bell, the court-appointed lead counsel for Camp Lejeune plaintiffs. About 500 people who Bell represents have experienced miscarriage, stillbirths and birth defects, his firm said.

On top of that, the women will have to show that Camp Lejeune’s contaminated water more than likely caused a condition that afflicts much of the general population.

Birth defects, for example, affect one in every 33 babies in the nation annually, while stillbirth occurs in about 1 in 175 pregnancies, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. As many as 26% of all known pregnancies end in miscarriage, or the loss of pregnancy, before 20 weeks, researchers have found.

“It will be a very scrutinizing process,” said Andrew Van Arsdale, an attorney representing 9,500 Camp Lejeune claimants. That process, he said, could go on for decades.

LaVeda Kendrix was stationed nearby at Marine Corps Air Station New River but trained, had meals and ran errands at Camp Lejeune from 1979 to 1986. Besides a cesarean section scar, there is no physical proof that Kendrix had ever lost the baby boy she did not get to bury.

“Now there’s nothing to indicate, but memories, that I gave birth to a deceased baby,” she said.

Decades of poison water

For more than 30 years, multiple sources contaminated Camp Lejeune’s supply wells, including waste from a nearby dry-cleaning facility and leaks from underground storage tanks on base, according to the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, which is part of the CDC.

There were extremely high levels of trichloroethylene, tetrachloroethylene, vinyl chloride and benzene — colorless chemicals that can cause several diseases, including cardiac defects and some cancers, the ATSDR said.

A pregnant woman would not need to be exposed to the poisoned water for a long period of time to develop birth defects, including neural tube defects, clefts and low-birth weight, according to Frank Bove, a senior epidemiologist who led the ATSDR’s investigation of the base’s contamination.

“You don’t need a long-term exposure,” he said. “It could be days or weeks.”

Birth defects can occur during any stage of pregnancy, with most occurring in the first three months when the baby’s organs are still forming, according to the CDC. Some occur during the last six months of pregnancy, as the tissues and organs continue to grow, the agency said.

Crystal Dickens, a Marine mechanic, spent about 10 hours a day working at Camp Lejeune’s motor transport pool beginning in the late 1970s.

“Because it’s hot, you’re burning up, you’re going to drink what you get,” she said. “We swam in it. We drank the water. We bathed in the water. We were totally exposed.”

Dickens, then 20, had three miscarriages in a row in 1979 before becoming pregnant with twins. At her six-month checkup, Dickens went into the Naval hospital and discovered there was only one heartbeat.

“There is no record whatsoever of my child who passed away in the womb,” she said.

‘Someone dropped the ball’

In the early 1970s, Kozobarich said adverse birth outcomes were so widespread among women on the base that some mothers treated it like a contagion, avoiding one another or hiding in their homes.

“Everyone was afraid,” she said.

Military leaders were alerted to the water problem as early as 1980 when they received a U.S. Army lab report containing a handwritten note that said the water was “highly contaminated,” Justice Department attorneys have admitted in court filings.

Camp Lejeune enlisted an outside lab to test the drinking water system in 1982 when the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency was expected to issue new regulations. The results were troubling, showing chlorinated solvents in the drinking water, according to Mike Hargett, the co-owner of the lab.

At the time, Hargett warned at least one higher-up at Camp Lejeune in-person about the dangers the chemicals posed to base residents. But, he said, he was dismissed in less than five minutes.

"That was disturbing to me that there was not a genuine concern that we need to do something about this today," Hargett said.

The most contaminated wells stayed open for over two more years, according to the ATSDR.

On April 13, 1984 — seven months before the first of the wells were shut down — Ann Johnson gave birth to a baby girl named Jacquetta, who had a cleft lip, a cleft palate and brain stem issues. Her right eye and right hand did not form properly, and she could not breathe or swallow on her own.

“She couldn’t cry out loud,” Johnson said. “You could see her open her mouth, and you could see tears roll down her eye, but she couldn’t make any noise.”

Seven weeks later, on the car ride home from the hospital, Jacquetta stopped breathing as her mother played with her curly hair.

“For 39 years, this has been at the back of my head,” Johnson said. “Did I do something wrong?”

Many people who were exposed went many years before they learned about the contamination.

In 1997, Jerry Ensminger, a Marine veteran, had just prepared dinner when he looked up at the television and saw a news report about the poisoning for the first time.

“I dropped my plate of spaghetti on the living room floor,” he said.

Ensminger had spent the last dozen years wondering how Janey, his curious and tough 9-year-old daughter, who was conceived and born at Camp Lejeune, could have died from leukemia.

“It was like God opened the sky and said, ‘Jerry, here’s a glimmer of hope that you’ll get your answer,’” he said.

In his first TV interview addressing the contamination since he left the Marine Corps, retired Maj. Gen. Eugene Gray Payne, who became responsible for Marine Corps installations in 2007, said leaders should have taken the warnings seriously, shut the wells down sooner and shown more compassion.

“There were personnel on base that were informed that there were contaminants, and they should have taken action,” he said. “Someone dropped the ball badly.”

In 2010, when Payne testified at a congressional hearing, he said he and the commandant had been briefed “over and over” that the water situation was better than it was.

“I think there may have been a reticence,” Payne said. “Fear that the backlash toward the negligence or potential negligence would’ve been tremendous. And I think there was a fear of saying it then. And I think that we made a mistake in not doing so.”

“It is a very real danger with any large organization that somewhere in the bureaucracy, someone is covering up what is potentially an extremely dangerous situation,” he added.

The Marine Corps, which is part of the Navy, directed comment to the Navy, which said it “remains committed” to addressing all Camp Lejeune Justice Act claims and encouraged eligible people to file administrative claims.

‘A complicated issue’

On Aug. 10, 2022, President Joe Biden signed the PACT Act, the “most significant expansion of benefits and services for toxic exposed veterans in more than 30 years,” according to the White House.

A provision of the bill allows people exposed to contaminated water at Camp Lejeune to file new lawsuits in the Eastern District of North Carolina if they have waited longer than six months for the Navy to resolve or respond to their initial claim.

With less than a year left to file, the Navy has received more than 93,000 Camp Lejeune Justice Act claims but has settled none, an official said. At least 1,192 cases have been filed in the North Carolina federal court so far, according to the court’s clerk, Peter Moore Jr.

Earlier this month, the Justice Department and the Navy announced a voluntary “streamlined process” to resolve claims in which the Navy makes settlement offers — from $100,000 to $550,000 — based on specific diseases and the duration of time spent at Camp Lejeune.

Miscarriage and female infertility cases are not eligible for the elective settlement.

Van Arsdale believes it was a “clever attempt” by the agencies to “pick off desperate” victims who may be susceptible to immediate cash offers or who feel they do not have much time left to live to endure a dragged out legal battle.

Many victims said they view the Camp Lejeune Justice Act as a path to justice, but the unprecedented road has been marred by obstacles, particularly for women who experienced birth issues.

In an email dated May 9, which was shared with NBC News, an attorney with the Navy Judge Advocate General’s office, which handles Camp Lejeune claims, told Van Arsdale’s firm that she is “specifically” looking for cases related to cardiac defect, kidney cancer, bladder cancer, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, liver cancer, kidney disease, Parkinson’s disease, multiple myeloma and lymphoma.

“Beyond that, they don’t want to see records on any other case types,” Van Arsdale said. “They are not even looking at this miscarriage issue right now, because I think it is a complicated issue.”

In a statement, a Navy spokesperson said the Navy’s Tort Claims Unit had “previously studied representative cases to better gauge the breadth and scope” of claims filed under the new law and to “develop systems” for processing them.

The spokesperson declined to disclose the findings of that study but emphasized that the Navy is not giving priority to any cases over others and that it is committed to processing “every claim as fairly and efficiently as possible.”

Yet for some men who suffer from one of the 15 illnesses and conditions related to Camp Lejeune that are covered by the Department of Veterans Affairs, progress has been slow.

“Even in those cases, we have to jump through a zillion hoops,” Van Arsdale said, “and they’re fighting us at every single turn.”

Lifelong grief

The victims can only wait as their health declines and they deal with decades worth of outrage and grief.

At 65, Dickens now suffers from congestive heart failure and end-stage renal disease. “I’m not me anymore,” she said.

Neither is Johnson, 58, who still goes to therapy to deal with the grief and guilt she feels over the baby she lost as she struggles with feeling that women in her position are “at the bottom of the totem pole.”

“The things we’ve been through, the pain and the anguish, doesn’t matter to anybody,” she said. “The women carry that for the rest of their lives.”

On a Tuesday evening in June, Kozobarich went back to "Baby Heaven" for the first time in 28 years.

Her daughter does not have a name because the chaplain at the Naval hospital had convinced Kozobarich and her husband, Larry, not to name her, mistakenly believing it would make their loss less painful.

“Baby Girl” is etched in her grave marker, next to rows and rows of babies who lived for only one day or none at all.

Kozobarich unfolded an essay she wrote about her daughter four years ago, on what would have been her 50th birthday.

“What would she have looked like? Whom did we lose?” she read. “Would she be brave and adventurous? Would she sail like her parents?”

“We would have loved you so much,” Kozobarich said, erupting in tears. "I will never stop mourning.”

Anna Schecter and Cynthia McFadden reported from Jacksonville, and Melissa Chan reported from New York.

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com