From babies to a trophy celebration, the surreal story of canceling the ACC tournament

The most surreal day in ACC tournament history began with apprehension disguised as hope. John Swofford, the league’s longtime commissioner, tried to defend the idea of playing basketball games when he met with reporters Thursday morning. The tone of his voice, somber and quiet, belied his words. He sounded resigned and unsure, and almost overwhelmed at how quickly everything was changing.

Only a couple of days had passed since the start of the tournament, on Tuesday. The ACC put out a statement then that it would go on as scheduled, despite the growing concerns over the spread of COVID-19, the coronavirus disease. Nothing much would be different, the league said, except that locker rooms would be closed to the media. That was the only change, and it was small.

What happened here after the ACC’s first statement of the week, released at 3:32 on Tuesday afternoon, was, in a lot of ways, reflective of what has happened all over the world at varying points in recent months. For a while around here, nobody saw anything like this coming. In Greensboro, the thought of a widespread shutdown related to the fear of the spread of disease had seemed so foreign, just days ago.

Inside of the Greensboro Coliseum, it had seemed so foreign that on Tuesday night, during North Carolina’s victory against Virginia Tech, the halftime entertainment was a real, live baby race. Parents stood on the edge of the court, holding their babies, and then released them onto the floor — the same floor where so much sweat and grime accumulates during the course of a basketball game. Then those babies crawled through who knows how many germs in pursuit of a prize.

By the middle of Thursday afternoon, the only people on that court were the workers who were taking the nets off of the baskets, and removing the cameras from atop the backboards. The stands were empty. Some light contemporary rock played softly over the public address system. In the old days, used to be that the ACC tournament didn’t really start until Friday. Now it was over on a Thursday, the coliseum workers packing it up and putting it away.

“My heart bleeds for Greensboro,” Swofford had said a few hours earlier, back when he tried to believe that this tournament could still be played after all, albeit in front of empty stands.

The connection between the city and the tournament added an emotional layer to everything that transpired here over the past three days. No city embraces the ACC tournament more than Greensboro, where the conference’s headquarters reside just seven miles south of the coliseum. The city has hosted 27 ACC tournaments but this was the first one since 2015, after the conference in recent years took its premier event to Washington, D.C., and Brooklyn.

A TRYOUT FOR GREENSBORO

There was a sense, before everything, that perhaps this week might be something of a tryout for Greensboro — a way for the city to secure its place in the ACC’s long-term rotation. Some of the greatest moments in ACC history have happened here, inside of the coliseum. Dean Smith coached North Carolina teams to championships here. Duke began its rise to national prominence in its early years under Mike Krzyzewski when it won the 1986 ACC tournament here.

The Greensboro Coliseum is where David Thompson and N.C. State beat Maryland in 1974, in overtime, in maybe the greatest college basketball game ever played. It’s where Wake Forest’s Randolph Childress scored 107 points in three days, setting a tournament record that still stands, in the 1995 ACC tournament.

It is impossible to walk into this building and not feel some of the history. If the wind and timing are right, it is impossible, too, to avoid the scent of pork cooking over hardwood coals from across the street at Stamey’s Barbecue, which has been around longer than both the Coliseum and the ACC tournament. Earlier in the week, the mood inside of Stamey’s was celebratory.

It always is during tournament week, said Chip Stamey, whose family has run the place for three generations. He sat on a stool, elbows on the counter, and told stories. Roy Williams, the UNC coach, liked to hit the drive-thru when he’d come through town on recruiting trips, Stamey said. He said Bobby Cremins used to love coming in during his years coaching at Georgia Tech.

On Tuesday afternoon, before the first game of the tournament, there was no talk of the coronavirus inside of the restaurant. It still seemed like a far-off threat — something for people to worry about somewhere else but not here, and not this week. Mitch Kupchak, the Charlotte Hornets general manager who played at North Carolina, walked through the dining room to a booth near the window.

All around, fans carried on conversations with each other, and with strangers who’d stopped in before walking across the street for some basketball. One of those conversations went like this:

“Who ya going for?” one man asked another, a few tables away.

“Carolina,” the other man responded. “Saw your hat.”

They both spoke with country drawls.

“Ever hear of Phil Ford?” the first man asked, pulling out a faded blue hat autographed by Ford.

Then another spoke up: “Did I tell you I met Tom Burleson here once?”

PLAYING TOURNAMENT WITH NO FANS

By the next night, the ACC had decided to hold the tournament without fans starting on Thursday. The decision followed hours of similar ones from other conferences and the NCAA, which had announced that its men’s and women’s tournaments would be played without spectators. Inside the Greensboro Coliseum, there was no formal announcement. People learned of the decision on their phones, or through word of mouth.

In the final minutes of Syracuse’s victory against UNC, in a game that turned out to be the last of this ACC tournament, fans quietly walked out. It was an odd scene. Usually at the end of the night session at the tournament, fans of teams that have lost fill the concourse and try to unload their tickets. Interested buyers often walk around holding fingers in the air, signaling how many tickets they want. Now there was none of that. People just left.

One group of Virginia fans lingered longer than most. They broke out into a playful cheer:

“Hell no, we won’t go!” they chanted, laughing, before they headed up the stairs.

“My brother and I, we’ve come every year for the last 20 years,” said Richard Austin, who wore a Virginia Cavaliers sweatshirt and hat. “You set your calendar around this.”

Austin said he and his brother grew up in the 1970s and ‘80s, and came of age when Ralph Sampson became the best player in school history. In those days, Austin said, “the ACC tournament was everything, right?” For them, it just kind of stayed that way, and when they learned that fans wouldn’t be allowed in, “We mourned,” Austin said.

A couple of sections over, Mike Pavlot stood near the front row of the stands, closest to the court. He’d traveled to Greensboro from upstate New York, about an hour outside of Syracuse. He and his son, Bryan, both wore Syracuse orange. Bryan collects college basketball media guides, and that’s what kept them lingering in the Coliseum. They hoped for one last souvenir.

“I guess we wish that somebody would have made a decision earlier,” Pavlot said while he walked out of the arena. “You know, we knew it was coming this way. Either don’t bring everybody in, or once you’re here — I mean, we’re here now. If it’s in the building, we’re already past that point. I don’t know what another two or three days will do.”

Both Austin and Pavlot said they were disappointed that the ACC didn’t even tell fans that they wouldn’t be allowed back in after Wednesday. That, it seemed, was another sign of the conference’s struggle to keep pace. Circumstances seemed to change by the hour and, sometimes, by the minute. The ACC followed moves that others made first.

CONSULTING ON EVOLVING SITUATION

For more than 12 hours, the conference planned to continue playing. When Swofford spoke on Thursday morning, he appeared 30 minutes behind schedule. He said he’d been on the phone with the commissioners from the Big Ten, Big 12, Pac-12 and SEC. All of them had been working together, Swofford said, to understand what they faced. The way Swofford spoke, it sounded like those leaders had reached a consensus, and formed solidarity.

“Right now we are ready to tip the afternoon session,” Swofford said. “We want to provide an opportunity to continue to compete in this tournament for our players. Our understanding and belief is that that is what they would want. It’ll be under unique circumstances and will certainly be a moment and a tournament that those players will remember for unusual reasons.”

He spoke for about 30 minutes. He emphasized how quickly everything could change. At the time, Swofford sounded as though he was trying to convince himself as much he was trying to convince others: the games would go on, empty arena and all.

“Hopefully, we won’t have to make another adjustment during the next few days,” he said.

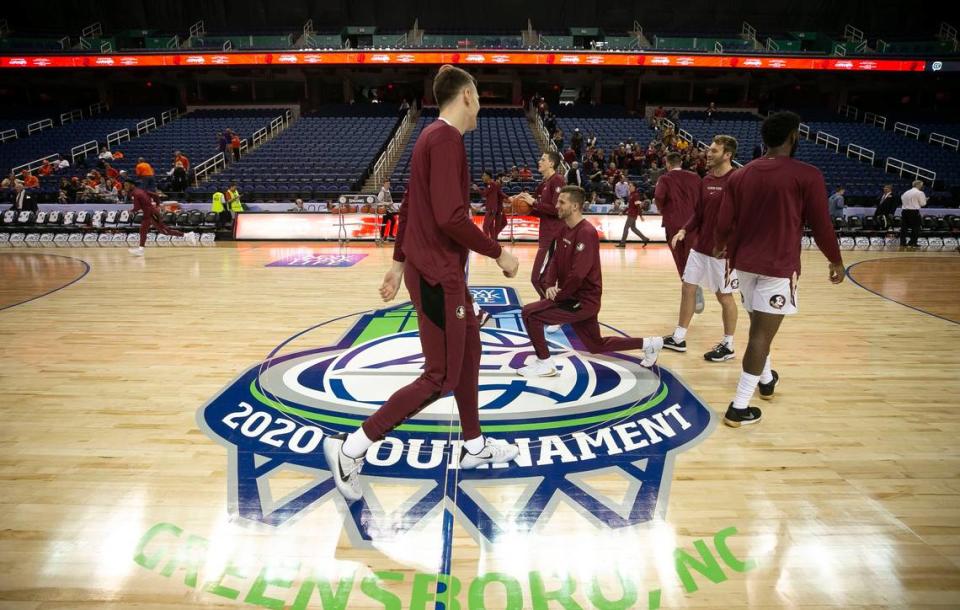

Soon, Florida State and Clemson took the court for warm-ups. They were supposed to start playing at 12:30 p.m. Inside of an empty coliseum, the noises of their pregame routines sounded louder than usual — the squeaks of their shoes amplified in a cavernous space.

The concourses, meanwhile, exuded an emptiness that felt eerie. The concession stands were dark. The huts where workers might sell beer, or ice cream, were pushed against walls. Curtains covered most of the upper deck. Less than an hour before tip-off, the sounds of warm-ups could be heard in the last row up top. Trainers yelled instructions. Players clapped and tried to energize themselves. The clock counted down to the national anthem.

In faraway places, meanwhile, other conferences made decisions that sent ripples toward Greensboro. Not even an hour after Swofford’s news conference, the Big Ten announced, at 11:49 a.m., that it was canceling the rest of its conference tournament. Accounts soon emerged on social media of teams leaving the court at Big 12 tournament, which was also soon canceled. Inside of the Greensboro Coliseum, a sense of inevitability settled in.

A conference official told one of the workers, manning a refreshment area, that she didn’t have to worry about making any more fresh popcorn. Both Florida State and Clemson, meanwhile, left the court, leaving confused the members of the Clemson dance team and the Florida State band. Soon Swofford made his way to center court. Photographers crowded around him, forming a circle. He took a microphone and addressed the few hundred people here.

Among them were parents of players, and families. A small number were coliseum employees.

“We’re all dealing with a very fluid and unknown enemy worldwide with the coronavirus,” Swofford said. “We don’t know entirely what that means for the future.”

Earlier, he’d said that the league hadn’t made any decisions without consulting public health and medical experts. He’d said that the ACC had been in regular communication with North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper. He’d said that the presidents and chancellors of the schools that comprise the ACC had been in favor of playing on, without fans present. But now, while he stood on the court not long after noon, he said those same presidents had finally come to a different decision.

“After a recent discussion of about 15 minutes ago with our presidents and athletics directors again, the league has made a decision to end this year’s Atlantic Coast Conference men’s basketball tournament as of today,” Swofford said. “It’s tough to say those words.”

RECOGNITION FOR FLORIDA STATE’S SEASON

He recognized Florida State, which finished the regular season in first place in the conference standings, as the league champion. He praised Clemson’s players and staff for returning to the court to watch the ceremony. The Florida State band played the fight song to an empty arena and the Seminoles’ mascot — a furry, two-legged horse named Cimarron — stood near the corner of the court, its hands on its hips. There were only few people for Cimarron to entertain.

Soon, Swofford faced more questions. A lot of them dealt with the timing of the decision.

“You can ask, why was it not made sooner,” he said. “It’s a fair question.”

He spoke of players’ and coaches’ fears, some of them heightened after the news that two NBA players, Rudy Gobert and Donovan Mitchell of the Utah Jazz, had tested positive for the coronavirus. Swofford spoke of talks with other conference commissioners and the conversations with health leaders.

“Their advice has changed, with some regularity,” Swofford said. “So it’s an extraordinary situation. None of us that are involved in it have ever really dealt with anything like it.

“And hopefully never will again.”

In the span of 44 hours and 42 minutes, the ACC released five statements related to the coronavirus. The first, on Tuesday afternoon, said things would mostly go on as usual during the tournament. The next, after the NCAA’s decision to hold its tournaments without fans, said the Wednesday night session would go on as planned. The next said the tournament would proceed without spectators. The next said Swofford would talk. The next said the tournament was canceled.

About four hours after that one, the NCAA tournament was off, too. The NCAA announced its cancellation in a statement at 4:16 p.m. on Thursday. In less than two full days, the ACC tournament went from racing babies to shutting down, and then the college basketball season was over, too.

It all happened as quickly as everything related to the coronavirus seems to have happened, whether in China in its earliest days or, more recently, in Italy, where parts of the country have essentially been on lockdown. And now the COVID-19 disease is here — no longer a specter but a reality that is already changing the way people live and work. It feels like those changes will last for a while.

By the time Florida State received its championship trophy on Thursday, basketball felt like an afterthought. When his players had walked off the court earlier, Seminoles coach Leonard Hamilton said, they’d “been disappointed” by the news that the tournament had been canceled.

“But I challenged them,” Hamilton said, “to be mature and understand the challenges of what’s going on in the world.”

It was difficult in moments to keep track of it all. News of changes, and then of cancellations, unfolded by the hour on Wednesday and Thursday, and sometimes by the minute. The ACC tried to keep alive a long tradition but, as it turned out, it never had a chance against the inevitability of cancellation. For the first time in its 67-year history, the conference canceled its men’s basketball tournament. By the end of the day, the league had suspended all spring sports.

For a while at the coliseum, meanwhile, the scoreboards in the corners above the tunnels remained illuminated. They showed that both teams had all of their timeouts. They showed that Florida State and Clemson had not yet scored. The game clock was frozen at 8:45 — the time remaining in warm-ups before Florida State’s players had walked off the court and learned that the game, and the tournament, were off.

Coliseum workers took down the tournament signage and packed things away. Those scoreboards remained on for some time, the game clock offering a reminder of when everything stopped, a moment frozen in time.

For two days, the ACC had tried to fight the inevitable and maintain hope. Now that was gone. The tournament was over before it really began. The last two teams here headed home. The coliseum became emptier. Nobody could be sure what might happen next.