Is This Baboon Skull a Clue to Egypt’s Lost Kingdom of Punt

When we think of the ancient world, we usually think of Egypt, Greece, Rome, Persia, India, and China. But when the ancient Egyptians thought of mysterious and wealthy kingdoms they spoke of “God’s Land” or the Land of Punt. Expeditions to this kingdom—which was rich in gold, ebony, ivory, and frankincense—were memorialized by the Egyptians on the walls of temples and alluded to in ancient folklore. But despite the fact that the Land of Punt was a real place and a major trading partner of Egypt’s, its precise location had been lost. Now new evidence, based on a mummified baboon skull, may help unlock the secrets of this lost civilization.

The Red Sea and ancient Egypt were part of a trade network that drove maritime technology for thousands of years. Punt also formed part of this ancient spice route and was well known for exporting luxury goods, in particular high-quality incense and prized sacred monkeys. Ancient sources suggest that travelers could reach Punt by journeying south and east of Egypt, leading some to identify the kingdom with Ethiopia or the horn of Africa, but the exact location of this country is a mystery.

One clue to unlocking this mystery is the prevalence of the sacred baboon (Papio hamadryas) in ancient Egyptian art and religion. Baboons can be found on statues, jewelry, amulets, and in temple artwork. Some baboons may have been pets, others are shown in art working as police animals and fruit harvesters, and many are associated with royal tombs. They even achieved quasi-divine status, being particularly associated with the baboon-headed god Thoth (who is also regularly depicted with an Ibis head), who was associated with the moon and wisdom. The image of the male baboon seated with hands on knees and surrounded by a lunar crescent is an archetypal image that was used in Egyptian artwork for a millennium. Figures of the seated baboon spread throughout the Mediterranean in the Middle Bronze Age, but the further you travel away from Egypt the less realistic the image of the baboon gets.

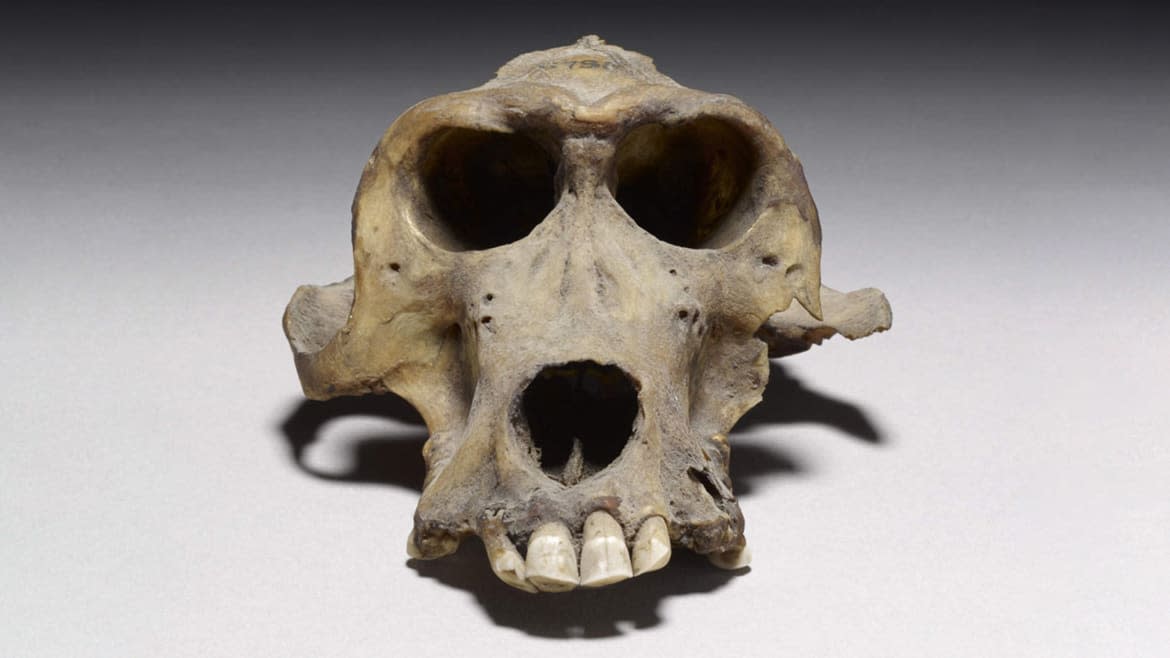

In the bowels of the British Museum, primatologist Professor Nathaniel Dominy of Dartmouth College discovered the remains of two hamadryas baboons. The baboons were mummified in the same seated pose that was so popular in ancient artwork and one has since been dismantled. The remains had been discovered at the Temple of Khons in ancient Thebes and were donated to the museum by the estate of Henry Salt, the British consul-general in Egypt between 1816 and 1827. Salt was one of a cluster of ethically questionable European diplomats-turned-amateur antiquities collectors who competed with one another to acquire as many antiquities as they could. Salt’s mummified baboons, however, are a curious discovery because baboons are not native to Egypt. There are no monkey species among the fossil records and ecological modeling suggests that baboon distribution has remained unchanged over the past 20,000 years. Where did these baboons come from? Dominy and his colleagues wanted to find out.

In an effort to identify their baboon’s birthplace, Dominy and his collaborators analyzed the chemical isotopes in the tooth enamel of one of the baboon skulls. The ratio of strontium isotopes in soil and water varies from region to region and is locked into a primate’s tooth enamel when they are young. By identifying the baboon tooth’s isotopic signature, the team hoped to pinpoint the place where the baboon had been born.

The results of the analysis confirmed what the team had suspected: the baboon had been brought to Egypt from somewhere else. Further comparative analysis of the remains of other baboons found in ancient Egyptian tombs revealed that while some were raised in captivity in Egypt, others had been born outside of the region. A large comparative study of over 150 baboons from 77 locations in East Africa and the Arabian Peninsula suggests that the British Museum baboon was born in a region that overlaps with modern-day Ethiopia, Eritrea, Djibouti, and parts of Somalia and Yemen. Given that many archeologists believe that Punt was roughly equivalent with this region, Dominy et al. argue that the baboon skull is the earliest known Puntite treasure. The discovery is a significant contribution that helps cement the theory that the wealthy Land of the Gods was located in the same area as Ethiopia and Eritreia.

Not every archaeologist agrees that these mummies are the earliest Puntite artifacts, however. Kathryn Bard, an archaeologist at Boston University who excavated a site on Egypt’s Red Sea coastline, told Science that ebony and obsidian fragments she discovered at Wadi Gawasis are older. During her excavations there she also uncovered Sudanese/Ethiopic style pottery fragments. For his part Dominy says that while the ebony artifacts from Wadi Gawasis are important, the widespread distribution of ebony throughout Africa means that they cannot be definitively identified as originating in Punt.

Regardless of which ancient remnant is the oldest, Dominy’s findings are significant. They help demonstrate the influence that ancient Ethiopia and Eritrea had on the cultural and religious thought of Egypt and, through Egypt, on the rest of the ancient Mediterranean. This recognition is important because Ethiopia and Eritrea rarely figure in popular histories of the ancient world. Instead, popular imagination focuses on ancient empires that have been traditionally—and, often, inaccurately—conceived of as white. Moreover, this research proves quite definitely that the baboon god is the lone non-native interloper in the pantheon of Egyptian deities. The baboon’s ascent from luxury import good, to immigrant worker, sacred guard dog, royal pet and, finally, deity is one of history’s great success stories.

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.