Get back: Florida Senate passes bill to criminalize getting too close to working police

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The Florida Senate has a message for those who get too close to cops: Get out of their way or go to jail.

Senators unanimously passed a bill Thursday that would create a first-degree misdemeanor for anyone who defies a warning and "impedes" police or other first responders when they’re at work. Despite questions previously raised by some Democratic lawmakers, asking whether it would prevent recording the police, the chamber approved the legislation (SB 184).

“This bill ensures (first responders’) safety, but it also ensures that the public's safety is prioritized, and it ensures ... we are containing a situation to make sure it doesn’t evolve into something more catastrophic,” said Sen. Bryan Avila, R-Miami Springs, the bill's sponsor.

A first-degree misdemeanor is punishable by up to a year in prison. That punishment would come if someone, ignoring a warning issued by a first responder, approaches, harasses or remains within 14 feet of them at work with the intent to impede the first responders, harass or threaten them with physical harm.

The bill defines a first responder as a law enforcement officer, a correctional probation officer, firefighter or an emergency medical care provider.

The bill doesn’t head to Gov. Ron DeSantis’ desk just yet. The House version (HB 75) awaits a final vote on that chamber's floor, but House lawmakers also have to resolve differences with the Senate.

“I know that we may reflexively jump to horrible situations (like) the murder of George Floyd,” said Sen. Jason Pizzo, D-North Miami Beach.

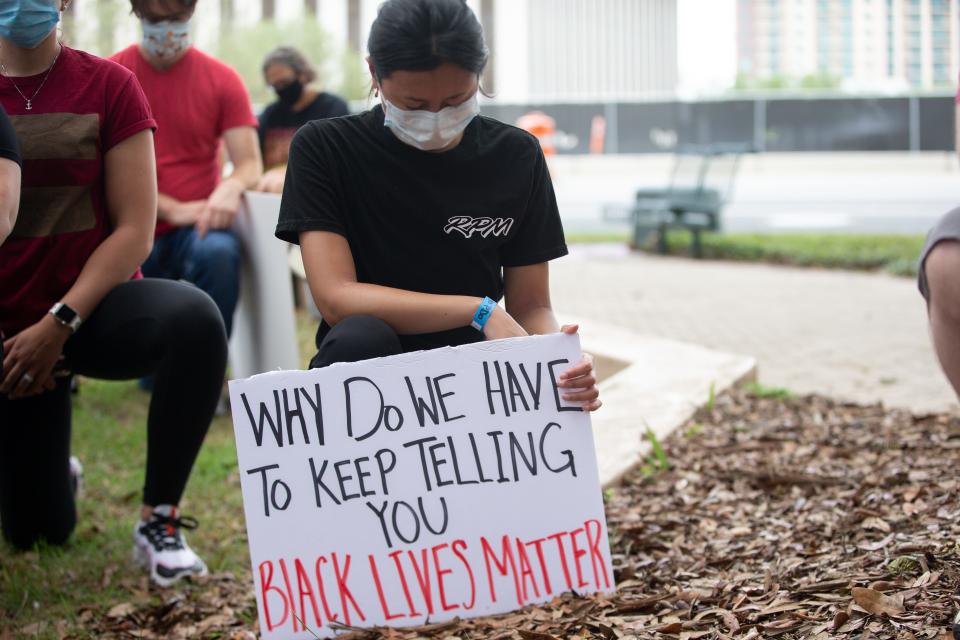

Floyd, an African American man, died in police custody on May 25, 2020, in Minneapolis. His death sparked widespread protests and renewed discussions about systemic racism and police brutality.

Pizzo also recalled standing near the wreckage of the June 2021 Surfside condominium collapse, watching parents trying to get past first responders to get to their kids.

“Certainly it was not unreasonable, however painful, to ask people to stay back for their own safety,” Pizzo said.

Constitutional concerns

Opponents, however, worry the legislation would prevent citizens documenting misdeeds by police in the line of duty. Some point to the cellphone video of the police murder of Floyd, which helped spark a racial justice movement.

During a recent committee meeting, Jasmine Burney-Clark of the Black-led Florida voting rights organization Equal Ground questioned whether, if the murder happened in the state under this measure, the police officer who killed Floyd would have been convicted.

“If you were 14 feet away, the obscurity of being able to record what actually happened and present that as evidence in court would probably not have rendered the verdict,” Burney-Clark said.

Derek Chauvin, the Minneapolis Police Department officer who was recorded kneeling on Floyd’s neck, was later convicted of second- and third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter.

While police body camera footage was used in the trial, the police department described Floyd’s death as a “medical incident.” That was before 17-year-old Darnella Frazier’s cellphone video shook the nation.

Travis Cains, a friend of Floyd's from Houston, where he grew up and lived for many years, said the community needs to be able to hold law enforcement accountable.

“(Frazier) was real close,” he told the USA TODAY Network-Florida. “If it wasn’t for her, Chauvin wouldn’t have been convicted.”

Abdelilah Skhir, policy strategist for the American Civil Liberties Union of Florida, pointed out there are already laws against interfering with law enforcement. He said the bill did far more than its title suggests.

“A distance-based ban is not a reasonable restriction on the (First Amendment right) to record police; it’s a nullification of it,” Skhir said during a recent committee meeting.

“Denying citizens the right to oversee and scrutinize the work of public officials is an attempt to silence and criminalize those who speak up for what they believe is right, which is a core aspect of our democracy.”

Bobby Block, executive director of the First Amendment Foundation, said the legislation was too broad and vague. He believes it will likely get overturned in court if it's enacted.

“What does ‘intent to impede, threaten or harass' mean? What activities is that?” Block said in an interview. “It’s vague. It’s open to discretion.”

The bill defines harassment as engaging “in a course of conduct directed at a first responder which causes substantial emotional distress in that first responder.” Block said that’s vague, too.

“One person can find your presence there emotionally distressful. Another person cannot care,” he said. “The traditional role of journalists is challenged by this law but so is the right of individuals in their First Amendment capacity to film and photograph what takes place in the public.”

Block pointed to how a federal judge last year ruled against an Arizona law that criminalized knowingly recording police officers 8 feet or closer if the officer tells the person to stop.

Bill sponsor say it doesn't affect recording

Sen. Bobby Powell, D-West Palm Beach, asked Avila during Wednesday's floor session if a police officer could find someone holding a phone as causing “emotional distress.”

Avila said he didn’t believe so. He maintains his Senate bill doesn’t affect video or audio recording.

“There needs to be a buffer in order to give enough space ... but to your question, this bill does not have anything to do (with) or prohibit or cause anything that would limit that ability of someone to report,” Avila said.

“Right now, it is a constitutional right for anybody to be able to do that,” he added. “To the bill itself, there is nothing that pertains to any of that."

A Senate Rules Committee staff analysis of the bill reads that a "criminal offense does not appear to be violated if the person to whom the warning is issued is within the 14-foot zone but the person does not have the required intent (to impede)."

Powell, and every other lawmaker on the Senate floor Thursday, voted 'yes' on the bill.

State watchdog reporter Ana Goñi-Lessan contributed. This reporting content is supported by a partnership with Freedom Forum and Journalism Funding Partners. USA Today Network-Florida First Amendment reporter Douglas Soule can be reached at DSoule@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Tallahassee Democrat: Lawmakers preliminarily approve no-go zone around first responders