Bad Axe in Rural Michigan Was a Hotbed of Hate. Then It Birthed My American Dream.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Nine months ago, in March of 2022, I had $101.99 in my bank account. I was broke and didn’t know how I’d make next month’s rent on my New York apartment. I had maxed out all my credit cards and had yet to contribute a penny to my upcoming wedding, which was set to take place in a few months. Despite these financial anxieties, I knew I would stop at nothing to finish my first feature film that I spent blood, sweat, years, and many tears on (along with all my savings).

This film of mine was also due to premiere at the SXSW Festival in less than 10 days. Bad Axe is the name of the documentary I made during the pandemic about my Cambodian-Mexican American family and the restaurant we’ve owned for over 20 years, called Rachel’s (after my mom). It’s also the name of my rural hometown in Michigan, where the story takes place.

I had sent the film to just about every sales agent and distributor in those days leading up to its world premiere. Most responded, “We love this film, but it’s just far too personal, and we don’t know if there’s an audience for it.” It was gut-wrenching, but my choices were to sell this film or move back home to Bad Axe and work at my parents’ restaurant for a few years to get myself back on my feet.

On Friday, Bad Axe is getting its theatrical release, something I wasn’t sure would ever happen. And, because of that, now I get to tell my story—my family’s story.

I moved back home to Bad Axe from New York in March 2020 with my girlfriend (now wife) to be with family during a very uncertain time. I knew I always wanted to share my family’s story. My parents, in my eyes, are the epitome of the American Dream. My mom is Mexican-American, and my dad is a Cambodian refugee. He came to this country in 1979 along with his widowed mother and five younger siblings, after escaping the Cambodian genocide known as the Killing Fields. While neither of my parents have an education beyond high school, they have more passion and resilience than anyone I have ever met.

In 1998, they decided to move to the Middle-of-Nowhere, U.S.A. (aka Bad Axe) to raise a family and start their own business: a donut shop. They quickly learned that selling donuts for 50 cents a piece in a community with fewer than 3,000 people wasn’t sustainable. Refusing to give up, they flipped the donut shop into an ice cream shop (which also failed) and then eventually into a fully operable restaurant that struggled to stay afloat.

My siblings and I grew up working alongside my parents at the restaurant, helping in any way we could. I’m sure many immigrant families with restaurants can relate to this, but the restaurant was basically our home. As young teenagers, I was the dishwasher; my oldest sister, Jaclyn, was the head cook; Michelle was a waitress; and my youngest sister, Raquel, was the baby, so she spent her days running around the restaurant spreading the love and joy we needed during that time. All of this still wasn’t enough, though.

Rachel's.

My two biggest fears growing up were losing our house and losing my dad. Countless nights were spent listening to my parents fight—always about money and what they would do if we lost the restaurant. Screaming, crying, and yelling: While I did grow up in a loving home, these are the sounds that filled our walls for many nights. As the survivor of genocide, my dad witnessed some of the most unthinkable atrocities during his years of living through a war; this trauma paired with the pressure of supporting our family often made it feel like he was a house of cards waiting to collapse in itself.

My dad had no way of processing his trauma. All of his time was spent working endlessly long hours, raising four children, and doing everything he could to keep the business alive. Even though it felt like we were fighting a losing battle, he was determined to build his American Dream, no matter how impossible it seemed at that time. While all of this was happening in the background growing up, there was another struggle our family had to navigate: Bad Axe.

Bad Axe sits in the thumb of Michigan. It’s a rural farming community with a population that is 97 percent white and has politics that lean heavily conservative. Like many places in America, red or blue, it has its issues with racism. While many people welcomed our family into the close-knit community, I can still vividly remember the instances when I felt like an outcast. At some point in my childhood I’ve been called all the slurs: chink, gook, spick, Jackie Chan, and, of course, have had the infamous, “Go back to China!”

The author's father, Chun Siev.

I always felt embarrassed when these instances took place, but why? I think part of it was that I never spoke out against these individuals. I’d cower, tell my parents, and they would teach me that it was wrong and to ignore it. Deep down, they knew that a 97-lb kid wouldn’t stand a chance on the playground if he spoke up for himself, and that it was safer to ignore it than to fight it.

When I moved away from Bad Axe in 2011 to attend the University of Michigan, I gained perspective on how different small-town life is from the rest of the world. Moving to Ann Arbor was the first time I had the opportunity to experience diversity. It was also around this time that my sister Jaclyn got her first full-time job in the automotive industry. Jaclyn, being the most selfless person I know, took her salary that year and reinvested it into the family restaurant, which was on the verge of foreclosure.

It was the first time my parents had the opportunity to put money into renovations. We removed all the fluorescent lights, swapped dirty square tiles for a classier laminate floor, and put in a beautiful cherry wood bar. Business slowly picked up, and Rachel's started to become the talk of the town. More and more people flocked to our restaurant to celebrate birthdays, first dates, anniversaries, and other special moments. My parents started making more friends, and it felt like our family had become a part of the community. I watched from afar as the restaurant took off, and I began my career working as an assistant in L.A. I was proud. After close to two decades, we finally did it. Our family achieved the American Dream. It was the perfect story that I knew I would one day make a film about.

Jaclyn Siev works in the family restaurant, Rachel's.

When I first picked up my camera in March 2020, it was not my intention to make a documentary. I always loved photographing and filming my family as a means of bottling them in memories. With all the free time I had, there was this instinct that these would be important times to remember. I filmed every day that year, capturing the renewed financial stresses of the pandemic, the racial reckoning of George Floyd, and watching community members turn on us for responding to the call to activism. During all of this my father’s trauma reignited itself from the past. It was about midway into the year when I had realized that our American Dream was at stake now more than ever.

It was almost as if everything we overcame in Bad Axe over two decades found new ways of challenging us. The pandemic posed new financial woes and exposed fears that everything we worked for would be wiped away. My dad felt helpless because Jaclyn had forced him to stay at home where he would be safer, which instead resulted in him having too much time on his hands to sit in his memories of when Cambodia crumbled. And then there was the Black Lives Matter movement.

My siblings and I responded to that call to activism, which resulted in a backlash of its own. Community members who we thought accepted us now turned their back on us and vowed never to support the restaurant again. One even wrote a letter telling us to go back to Cambodia. And the scariest part of all, it was no longer ignorant kids on the playground calling us “gooks,” but actual Neo-Nazis with AR-15s, who hailed Hitler and left us death threats.

During the pandemic and amidst the Black Lives Matter movement the family encountered white supremacists who called the Siev family racial slurs and threatened them with death threats.

I began editing all of this footage together, and the film started to take a life of its own. I had years of pent-up anger against my hometown and decided this would be a film calling Bad Axe out on its shit. Rather than focusing on the personal lens of telling my family’s story, I used news soundbites and visuals that, with a heavy hand, unearthed the political bitterness I had against my home town. I had lost complete sight of the story I always wanted to tell. When I showed that first rough cut to my family, they told me, “You cannot show this to anyone.” We had a long, emotional talk those following weeks, and I pondered the question of why I was even doing this.

When March 2021 rolled around, pandemic life was the new normal. I didn’t have an ending to my film and I still needed to answer that question I was left months to think on. I became private about sharing anything about the film with my family. But then, as seen in the ending of Bad Axe, a miracle happens. It didn’t have anything to do with Bad Axe, the political state of our country, the pandemic, or anything else. Instead, it was a joyous moment that brought me to tears, and gave me hope for my family’s future.

It illuminated what my grandma had all made possible through her sacrifice 40 years ago, when she arrived in this country as a widow with six children. I won’t share what this moment is, because I am hoping you will go and see the film if you are reading this. But it made me remember that I began this documentary to capture my family’s story. I wanted to share their story because of the deep affection and unconditional love I have for them. Bad Axe has given us that bond, which is why that love extends beyond my family to this place where I harbored so much anger for years. So, with this clarity, I went back to the edit bay with an open heart and my family's input. Like everything we’ve accomplished in life up to this point, we’ve done it together.

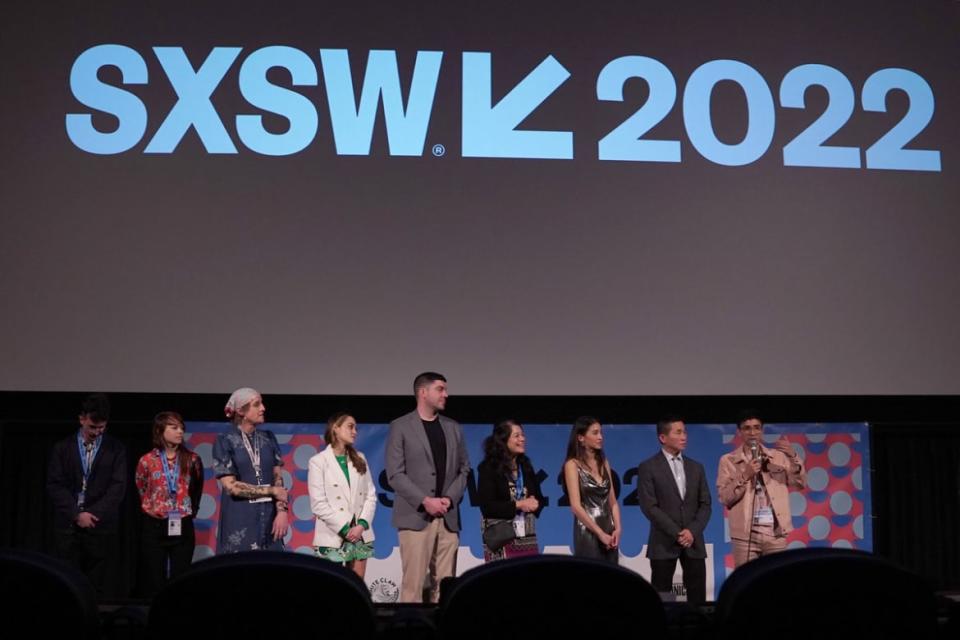

David Siev speaks at the 'Bad Axe' premier at SXSW in Austin.

Those days leading up to our world premiere at SXSW, my lovely fiancée and producer assured me everything would be all right, whether or not we found a way to sell the film. She’s been my biggest cheerleader and my backbone throughout this whole process.

Jaclyn and my brother-in-law, Mike, caught wind of my financial woes and wrote me a blank check. They told me I had earned it and needed to take care of myself. That blank check still sits in my desk today. My family had already helped me get this far, and I didn’t want to place the financial burden of making this film on them. Bad Axe is my American Dream, and I figured if my parents could achieve theirs when they were my age with three kids and a struggling donut shop, I could find a way to accomplish this on my own.

Showing up to that premiere was a dream. Bad Axe received three standing ovations at all of our screenings and won two of the top awards. I had forgotten the stress I was under to sell the film. My family and I soaked it all in. One week later, we sold the film to IFC. I was able to take a deep breath, knowing I could make my rent, pay off my credit card debt, and fully contribute my share to my wedding fund.

(L-R) Chun Siev, Rachel Siev, Jaclyn Siev, Kat Vasquez and David Siev pose at the Critics Choice Association Inaugural Celebration of Asian Pacific Cinema & Television at Fairmont Century Plaza in Los Angeles.

Coming off the high of SXSW, it was time for us to face the town of Bad Axe with our story. The anxiety had been building for months about how the community would respond. A year before this, we released a crowdfunding trailer that became very controversial when community members started to leave negative comments and accuse me of lying about my family’s experience. We invited mainly the crowdfunding donors who had contributed to our campaign, but to our genuine surprise, we received ticket requests from many people in our community who we knew were skeptical.

The tension in the room felt like it lasted hours. When the credits rolled and the lights came on, we received a standing ovation from every person in that room. Audience members, some of whom vowed never to support the film, came up to us after and said, “I am sorry... I am sorry for judging your family and your story before I had the chance to see it for myself.” It was as if they no longer viewed us as being “the other side,” but rather as their fellow humans and community members.

The film needed to come from a place of love to humanize the issues at hand. And because our community started to see themselves as the imperfect people we are, they were willing to have a conversation. That’s the first step to change. Witnessing this dialogue take place before my eyes made me realize there is no ceiling for the power of cinema to create change.

My American Dream is not the same as my parents’. My parents wanted to afford a better life for my siblings and me that they never had. As tough as times were growing up, they always achieved that. Bad Axe is my American Dream. And it is not because the fruits of my labor have afforded me that same stability my parents were always fighting for, but because that’s given us something we did not have growing up—a voice. Sharing our voices and our stories is how we open up the idea of what the American experience is. It’s how we cement ourselves and our identity in this country. My family’s story is as American as any, and to be seen as just as American as any of my neighbors, or anyone in Bad Axe, that is my American Dream.

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.