Baker: Lichens found to be entire ecosystems in miniature

It’s been estimated that some 20,000 species of lichens cover 6 to 8% of the planet’s land surfaces, even though referring to the existence of even one species of lichen is just plain crazy talk.

In 1869, Swiss botanist Simon Schwendener published his “dual hypothesis” on lichens, in which he suggested that lichens are not single organisms, but a compound of a fungus and an alga.

Crazy talk. Virtually all lichenologists of the day gave him hell for his trouble, because it was obvious that all the well-known, readily identifiable forms of lichens were individual organisms. Even the renowned English fungus biologist, Beatrix Potter (yes, that Beatrix Potter), politely commented, “You see, we do not believe in Schwendener’s theory.”

Lichens found to be an example of 'symbiosis'

But he wasn’t crazy. By the turn of the century, lichens had come to be viewed as the poster child for the newly minted ecological concept of “symbiosis,” the intimate collaboration between individuals of quite different species to the benefit of both.

What was nuts then and remains so today is the scientific practice of calling such an association — partnership may be the better term — of two completely different organisms a species. And yet that’s the way it’s done. By convention, lichens get the same Genus species name as the fungal component of the lichen.

Does this cause problems? Interminable. Consider a species of fungus that can form a symbiotic partnership with three different species of algae. Each of the three resulting lichens will have a different physical appearance and ecology from the other two, and yet all have the same scientific name as the fungus.

But it’s worse than that.

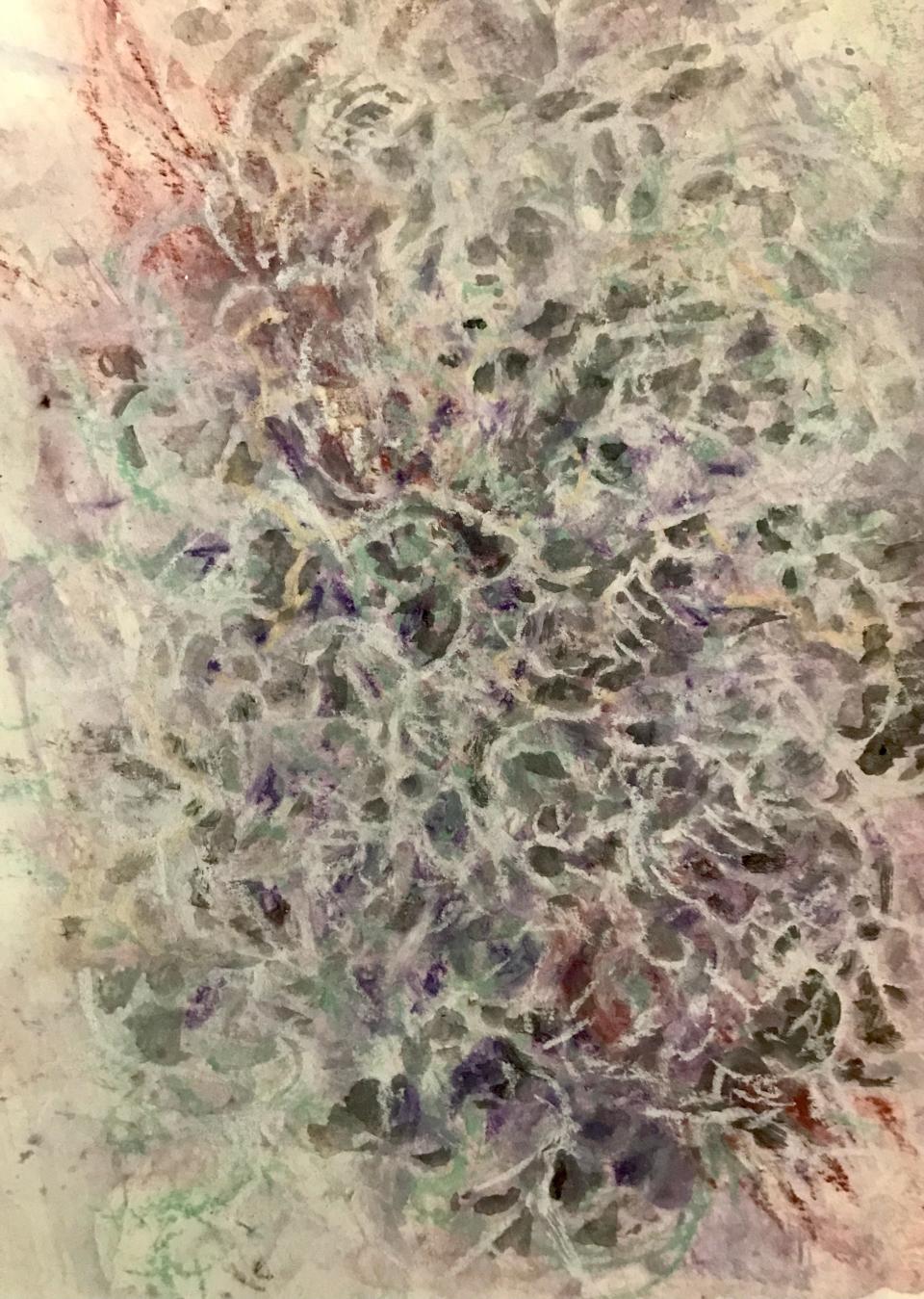

In the early 1900s, lichens were understood as composite “organisms” in which a network of fungal threads (hyphae) provide a safe haven for numerous single-celled algae. In return, the photosynthesizing algae provide the fungus with carbohydrates it can’t manufacture.

In addition to sheltering the algae, the meshwork of hyphal threads capture moisture and nutrient-laden dust from the air which both organisms require, leading to the neat outcome that the resultant lichen can live in environments where neither of the two partners could survive alone.

Lichens are found all over earth

Indeed, there are few places on earth where some form of lichen isn’t found. Lichens are the dark brown patches of scum spreading across the asphalt shingles on the roof of an old, dilapidated shed. They are the marmalade orange crusts blotching boulders facing the Arctic Ocean along the coastline of Canada’s Ellesmere Island, and the otherworldly leafy or branching structures adorning tree branches and trunks in both temperate and tropical rainforests.

By the mid-20th century, it was discovered that in especially moist environments, certain fungi will form lichens with photosynthesizing bacteria (Cyanobacteria) instead of algae, requiring the invention of some new terminology. The lichen’s fungus is referred to as a mycobiont, and its photosynthesizing partner, the photobiont, which is also called either a phycobiont if it’s an alga or a cyanobiont if a bacterium.

However, the basic idea of one fungal species and one photosynthesizing species per lichen remained the same, and that was certainly what I taught in my Introductory Biology courses for almost 40 years.

But on July 26, 2016, a research paper by a University of Montana lichenologist, Toby Spribille (now at the University of Alberta) and colleagues, made the cover of Science, probably the most respected scientific journal in the world. To say his work shook things up would be to put it mildly.

Spribille found that fungus-algae lichens from across six continents all contained a certain form of yeast cells that appeared to be crucial members of the partnerships. Since then, further work by his team and others have found stable groups of bacteria and yeasts associated with every group of lichens.

“Some have more bacteria, some fewer; some have one yeast species, some two or none. Interestingly, we have yet to find any lichen that matches the traditional definition of one fungus and one alga.”

So it’s falling out that lichens are not an organism, not a symbiotic relationship between one fungus species and one algal or cyanobacteria species, or even a trio of one mycobiont, one photobiont and one yeast.

Lichens referred to as an example of a holobiont

Lichens are entire ecosystems in miniature, what many biologists are now referring to as an example of a holobiont, a diverse assemblage of organisms that behaves as a unit.

Another classic example of a holobiont is a human being, with our 10-100 trillion symbiotic bacteria directly impacting our digestion, metabolism, immunity, developmental processes, and brain functions.

Here’s mycologist (fungus biologist) Merlin Sheldrake addressing the philosophical implications of where our expanding studies of holobionts are leading us: “If the word cyborg — short for cybernetic organism — describes the fusion between a living organism and a piece of technology, then we, like all other life-forms, are symborgs, or symbiotic organisms.”

Ken Baker is a retired professor of biology and environmental studies. If you have a natural history topic you would like Dr. Baker to consider for an upcoming column, please email your idea to fre-newsdesk@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Fremont News-Messenger: Research on lichens changed our thinking about biology