Baker: Recalling efforts made to track the plight of turtles

“Geezo-Pete! We needed three men and a fat boy to handle that’n!”

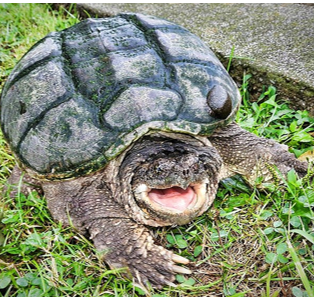

I silently hoped I wasn’t the fat boy, but I knew what the head field biologist meant. We’d just fixed a radiotelemetry transmitter to the top shell of a seriously unhappy snapping turtle that had blundered into the trap we’d set out in her pond earlier that day.

Turtles don’t have any teeth, but the upper and lower jaws of the aptly named snapping turtle are like a matched set of steel-edged letter openers that could easily shorten a fellow’s selection of digits, and this one had given it a good go.

Animal emotions: Ken Baker: Do animals grieve like humans?

While one of us struggled to keep the snapper on the lab bench, my job had been to hold a bent piece of wire hardware cloth over her head to block her repeated efforts to sever one or all of our limbs. But my eyes mostly were fixed on our instructor, who was demonstrating how to fix a radio transmitter the size and shape of a 9-volt battery to the animal’s carapace (upper shell).

Snapping turtles are primarily aquatic, spending most of their lives hunting fish, amphibians and any small bird or mammal unlucky enough to get within striking distance of its surprisingly long and flexible neck (the source of its species name, Chelydra serpentina). Trying to fix an expensive transmitter to its slime-covered shell would have been a non-starter.

So instead, the biologist used a piece of coarse grade sandpaper to scrape a small patch of slime from the top of its carapace and down into the shell’s dry, bony tissue. He then epoxied the transmitter onto the bare spot and coated it over with several layers of a polyurethane lacquer.

Art, naturally: Meet Your Neighbor: Megan Bee finds inspiration for music in the natural world

Efforts included tracking a snapper for a week

For the next week, we tracked the snapper’s movements within the pond using handheld antennas connected to receivers that picked up the little “ping” sounds the transmitter on her back sent out to the world.

Some 30 years later, one of my own students and I spent a good part of one summer tracking the movements of several Eastern box turtles using a similar radiotelemetry technique, but this time through a stinging nettle and poison ivy-rich deciduous forest instead of an algae-covered pond. Since box turtles aren’t aquatic, we didn’t have to sandpaper the dry carapace before affixing a much smaller transmitter.

The high-backed (rather helmet shaped), yellow-blotched carapace of the Eastern box turtle, Terrapene carolina, is familiar to most folks who have spent much time roaming the deciduous woodlands of the eastern states..

And yet not so familiar as it had been several decades ago.

Turtles around the world are in decline

Turtle abundances around the world are in general decline. The plight of some species, like the leatherback and loggerhead marine turtles have been widely publicized and led to broad support of conservation efforts, especially those designed to protect their ocean shore nesting grounds.

But many freshwater and terrestrial turtles have also seen steep declines in abundance over the past several decades. A report published earlier this year comparing the results of a five-year survey (1978-1982) of box turtles in a southeastern Pennsylvania forest with a six year survey (2015-2020) in the same forest found a 71-74.1% decline in population over the 40 years of the study.

Similar box turtle declines have been reported in Maryland (77% over 40 years), Delaware (75% over 34 years) and Indiana (47% over 20 years). On the other hand, a ten year study of 39 locations across North Carolina published in 2021 found no notable changes in box turtle numbers at any site. It is unclear why that study’s results differed so strongly from the conclusions of most other surveys.

What is clear is in most of its range, box turtle population declines are triggered by fragmentation of their forested homes, vehicular strikes, removal as pets and harassment by off-leash dogs — all of which are related to increased human activity in or near their woodland habitat.

Although snapping turtle populations generally are considered in fairly good shape, increasing road traffic has also become a serious problem for them, since females move inland — commonly quite far from the stream or pond they normally inhabit — to lay their eggs.

Climate change is an enemy of reptiles

And then there’s climate change, the special enemy of reptiles.

Most turtles, all crocodiles and alligators, and some lizards have “temperature-dependent sex determination.” Above a certain threshold temperature (typically during the middle third of an egg’s development period) most hatchlings will be female; below a somewhat lower temperature, most will be males.

Research suggests an increase of as little as 2 degrees F in average temperature during egg development can lead to population sex ratios that are heavily skewed toward females. It’s noteworthy that the planet’s average surface temperature has increased by about 1.8 degrees since the late 1800s.

By choosing where and how deeply a female buries her eggs, she can control nest temperature to some extent. However, it’s not known if turtles’ nesting behavior is adapting to observed climatic changes or, if not, what that might mean for the reptiles’ long-term survival.

Ken Baker is a retired professor of biology and environmental studies. If you have a natural history topic you would like Dr. Baker to consider for an upcoming column, please email your idea to fre-newsdesk@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Fremont News-Messenger: Adventures accompany trailing the plight of the snapping turtle