The Band’s Masterpiece Turns 50 Without a Touch of Gray

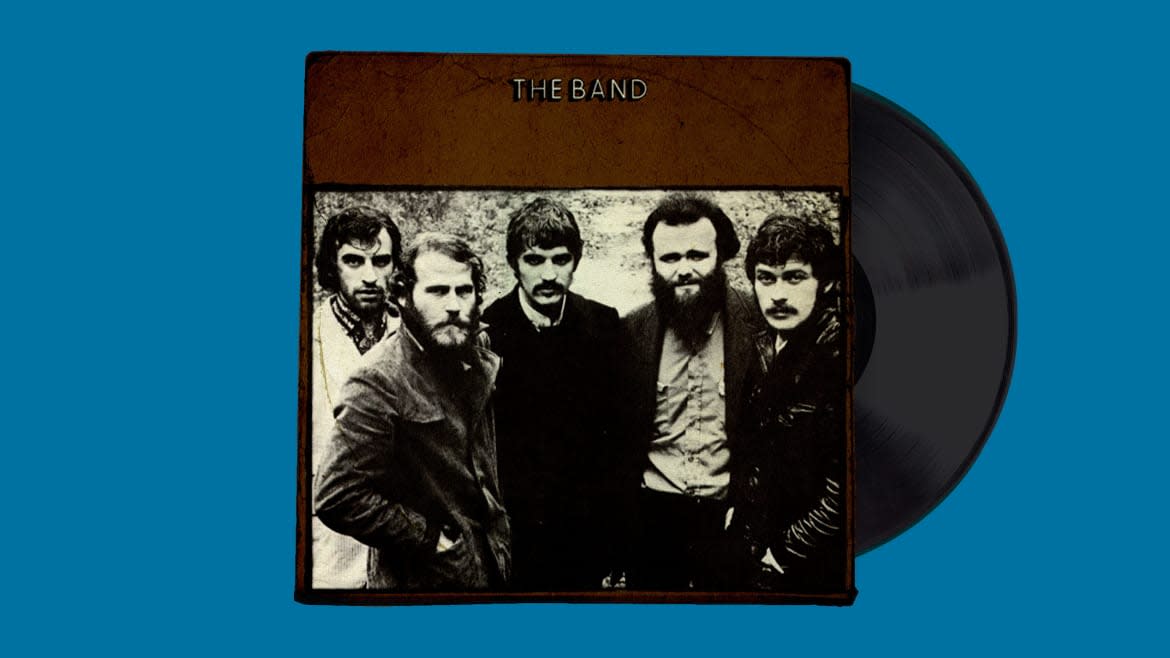

I will not—I swear—be sucked into talking about the profundity of The Band’s Brown Album, which has wound up the record’s de facto title because the original bore no title on its cover, just “The Band,” and because the record jacket was… brown. There’s been more pseudo-profundity spewed about this record than any other I can think of, except maybe Sgt. Pepper. So I’m not going to go there.

I was still a teenager when I first heard the Brown Album, which came out in 1969, half a century ago, and what I liked about them was that they were a rock and roll band that didn’t sound like a rock and roll band. They certainly didn’t sound like kids. They sounded like grown-ups singing about grown-up things (and what teen doesn’t want to be a grown-up?). There were songs about old men who hated being old, and burglars and farmers and defeated soldiers who couldn’t catch a break. Even the love songs sounded messy and complicated, sad and happy and—splitting the difference—bittersweet.

The lyrics were just the icing. It was the music that held me. The way they crafted songs told you they’d listened to every conceivable style and genre, from folk songs to rhythm and blues. In their songs you heard brass bands, the church organ, and those eerie sounds from cheesy sci-fi movies along with electric guitar and bass and drums. They’d soaked it all up and they took what they needed wherever they found it. They weren’t alone in that. If you wanted to be musically hip in the ‘60s, you learned to festishize the past. But no one else sounded like The Band. And no one, not even the members of the group, was exactly sure why that was.

Robbie Robertson on The Band’s ‘Music From Big Pink’ at 50: ‘It Sounds Like The Band I Remember’

In the new documentary Once Were Brothers: Robbie Robertson and the Band, (based on Robertson’s memoir Testimony), which charts the history of the group, Richard Manuel recalls how it felt making their first two records, how confused he was about the music they were creating, how hard it was to define because “there was nothing to compare it to.” And yet it was a kind of blissful confusion because the music made him so happy. “I really liked it,” he said. “I just hope other people do.”

Watching the first half of this new documentary—which covers everything up to the creation of Music From Big Pink (1968) and the Brown Album (1969)—is like inhaling helium. The second half—where they grew apart, and some of them fell apart—is like getting clunked on the head with the helium tank. The biggest casualty of their break-up in 1975 was that intense bond they’d had, not just as friends but as musicians. No group ever had better parity: all of them could play, three of them were terrific singers, and three could write songs. The sound they produced was loose but never sloppy, dense and yet airy, with the veteran precision of a classical string quartet where voices and instruments weave in and out in perfect balance. The sum of the sound was greater than the parts, and those parts were considerable.

Those songs have the specificity of dreams as well as their surreality. We hear all these names: Jake, Annabella, Virgil Caine, Jemima, W. S. Wolcott. But we don’t know much about them. The words and situations are vivid and concrete (“Standing by your window in pain, a pistol in your hand”), but there’s just enough vagueness in the lyrics to force a listener to complete the picture being drawn. Bruce Springsteen puts it well in Once Were Brothers when he says The Band’s music was like nothing “that you’ve ever heard before and it sounds like you’ve known it forever.”

The Brown Album has been in heavy rotation at my house for half a century. It’s got more staying power than almost any other record I’ve ever owned. If time teaches us anything, it’s to be modest about what we cherish, because those things change. Passions come and go. That said, I believe most of us stick with the music we heard when we were young. A lot of it’s habit. But some things do endure. The Brown Album is one of those things.

Americana as a musical genre starts with this album. You can call that a blessing or a curse. I know I have. But truly, there was nothing that sounded like the Brown Album, or Big Pink, before they first appeared in 1968 and 1969.

If you love this album too, go grab a copy of the 50th-anniversary box set edition (new mix on vinyl and CD, along with the usual outtakes and the recording of their Woodstock performance, some promo photos, and a DVD video doc about making the record that’s a lot better than most things like this). Before this set appeared, I would have sworn to you that I was done with box sets. Apparently not. Not when they sound this good.

As soon as I heard a streamed version of the newly remastered version of “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” I reached for my sack of highfalutin critical terms and came right up with: Holy shit!

I won’t say it was like hearing a new song. It was an old song heard anew, like seeing a familiar painting after it’s been restored. It’s the same painting, only more so. Everything about the recording sounded bigger, clearer, with more clarity and space in the music. If anything it sounded more like musicians actually sitting in a room and playing and singing together. When I got my hands on the vinyl version of the whole album, it sounded even better (they’re cut at 45 RPM by the way, and anything will sound better in that format, but this is way beyond the minimum upgrade).

I was happy when I saw my opinion echoed by Robertson in an interview in Billboard (hey, I wasn’t imagining things): “I went back to the original masters with Bob Clearmountain [the genius sound engineer credited with this remix] and we thought, ‘Let’s make this better for now for what we couldn’t do back then. Bob—who is one of the best in the world at doing the stuff—brings up the tapes and he starts to work and do his magic on it. Then I go to his studio, we’re listening to this and we’re like, ‘You can’t do this. We can’t do that. This is like taking a painting and saying, ‘Let’s enhance it.’ We couldn’t do that. What we could do, we discovered, is we can take the original tapes, put it just like it was, but with today’s technology, we can present it with less hum and hiss and things that you got from tape and everything back then, in a more pristine way. You can hear more of the music, more of the air in it, and present it so you’re inside of it more—that we could do.”

The Band made two albums as good as anything in American popular music before the well started to run dry. There are some good songs on the third album, but by then it’s like they’d started believing their own press (that they had laid bare the soul of old rural America, which I always thought was mostly horseshit). But that doesn’t mean they didn’t write a lot of fine songs. They went on to make more albums before they busted up in 1975, but other than the live album Rock of Ages, with those exquisite horn arrangements by Allen Toussaint and performances without equal, nothing as memorable as those first two records ever emerged again. But two great records, records that sound as unique today as they did when they first appeared? You have to tip every hat you own to that score.

Got a tip? Send it to The Daily Beast here

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.