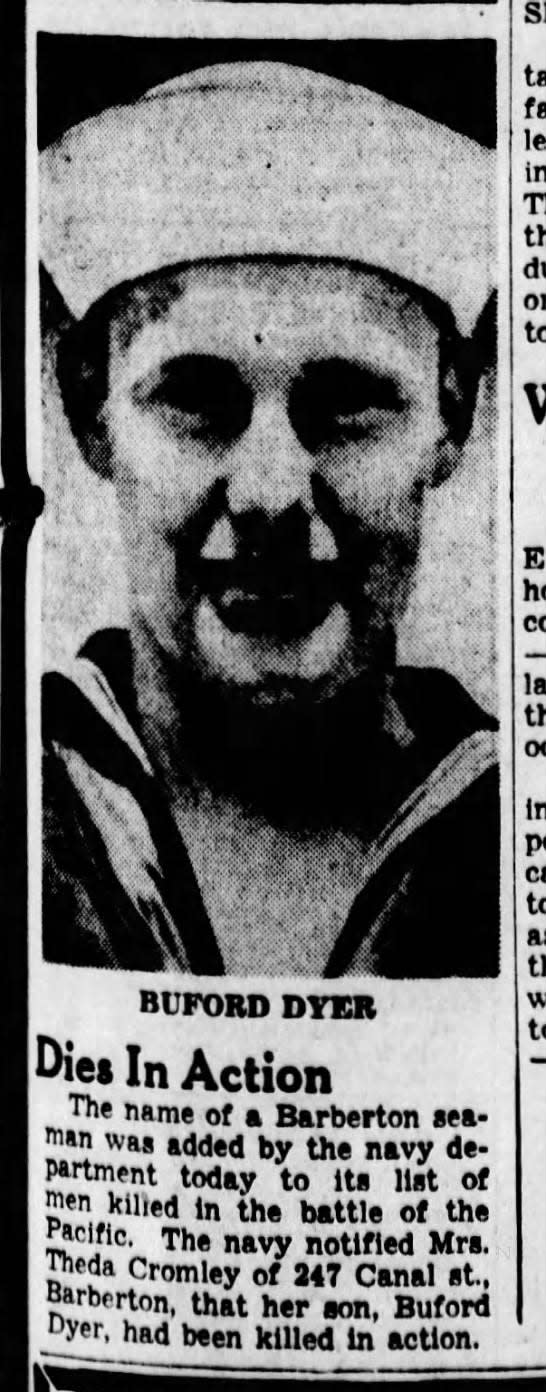

Barberton sailor Buford Dyer: A life cut short at Pearl Harbor 80 years ago

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Eighty years ago exactly, Buford Dyer’s day would have started much like any other, with the young Barberton sailor starting his work early aboard the USS Oklahoma in Pearl Harbor. It wasn't long, however, before the Japanese attack began, just before 8 a.m.

Before the attack was complete, Dyer's ship was destroyed and he, along with hundreds of shipmates, had died. For almost 80 years, the place of his death remained unknown to his family, his friends and the world.

A brewing storm

Dyer entered the Navy on April 22, 1940, in Cleveland just as the U.S. was crawling out of the Great Depression.

The world was at war, but the U.S. remained officially neutral. Then, abrupt and brutal, came what Roosevelt called "a date which will live in infamy."

By the time Dec. 7, 1941, arrived, Dyer would have settled into his duties aboard the Oklahoma. It’s probable he relished the warm Hawaiian weather, thinking about the snow and cold back in Barberton, where his mom and two younger brothers would be preparing for Christmas.

Over the summer, U.S. relations with Japan had worsened, and Dyer would know war was likely. On Nov. 26, U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull had delivered a diplomatic note requiring Japan to give up its territorial goals in China and Indochina and end its pact with Germany and Italy before trade would be restored.

The attack on Pearl Harbor, killing Dyer and hundreds of his crewmates, came 11 days later.

Buford Dyer and the Oklahoma

Any sense of order for Dyer and the other 1,100 sailors aboard the Oklahoma jolted to a jarring end in minutes at about 7:55 a.m. on Dec. 7 as Japanese warplanes descended on Pearl Harbor.

The USS Oklahoma was lined up in "Battleship Row" with six other warships near Ford Island, one of 80 naval vessels in the harbor. Three U.S. carriers, a prime target of the Japanese, were all at sea and escaped the attack.

Using six carriers, 350 planes and five small submarines, the Japanese military carried out the surprise attack. A declaration of war came two hours later.

In the first wave, about 183 planes took part, many attacking with bombs and torpedoes. Because the carriers were absent, the battleships, including the Oklahoma, became the primary targets.

Dyer likely would have been aware of the attack before the first torpedo hit his ship; the crew began participating in countermeasures as U.S. artillery scrambled to fire at the planes. The counterattack gained momentum as the surprise assault continued.

By 8:03 a.m., the Oklahoma and USS Arizona had been badly damaged by torpedo strikes, and the USS Nevada suffered its first hit. The USS California had also been hit and, like the Oklahoma and Arizona, was leaking oil. As the Oklahoma listed, the commander gave the order to abandon ship over the starboard side. It is not known if Dyer heard this order, but it's now known he could not comply.

Five torpedoes had struck the Oklahoma and the ship capsized in 15 minutes, sinking into the mud near Ford Island and trapping many of the sailors, including Dyer, inside. Some were able to escape into fiery waters fueled by leaking oil. A few were rescued from the ship in the days following the attack.

A second wave came about 9 a.m., but by that time, the Oklahoma was lost, along with the Arizona. The two battleships were the only ones damaged beyond repair.

More than 4,500 miles away at home, Dyer’s brother Jhugh “Jay” Dyer listened to news of the attack on the radio. Before the broadcast had ended, the 17-year-old decided to enlist in the U.S. Marines.

Buford Dyer and 428 crewmates were killed. In all, 2,403 people were killed in the carnage.

The next day, the U.S. declared war on Japan.

A son of Barberton

Little is publicly known of Buford Dyer’s life, either in the Navy or before he began his service.

Much of his military record would have been destroyed, according to Sean P. Everette, who conducts outreach and communications for the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency.

"We don’t have any record of his responsibilities onboard," Everette said via email. "Most records in those days were kept on the ship and they were destroyed during the attack."

We do know he was born in Tennessee, according to honorstates.com, which uses government archives and public records to provide information on U.S. service members killed in action.

He was born Jan. 31, 1922.

His was a Seaman 1st Class in the Navy and the son of Dillard Dyer, who died 1934, and Thena Cromley, who remarried after she was widowed.

It is not clear when the family moved to Barberton.

Dyer and his brothers Jay and Chester attended Barberton High School. By the time his mother was notified of his death two months later, his brother Jay had enlisted in the Marines and Chester still attended high school.

Dyer was awarded a Purple Heart, Combat Action Ribbon, World War II Victory Medal, American Campaign Medal, Navy Presidential Unit Citation, Navy Good Conduct Medal, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal and a Navy Expeditionary Medal.

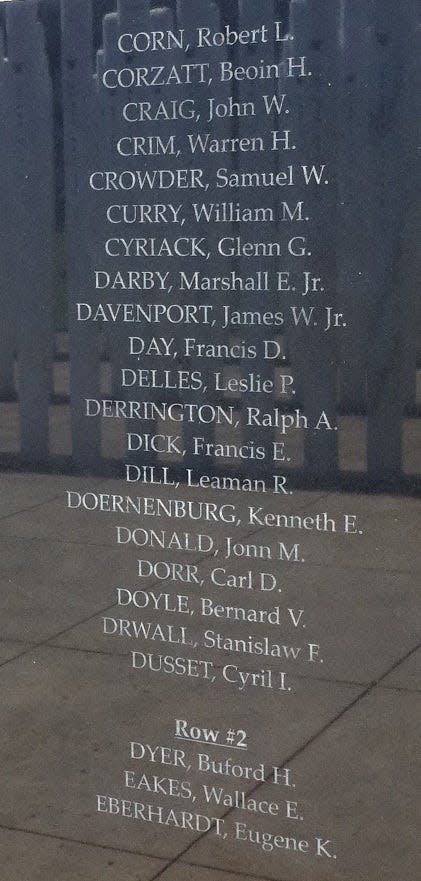

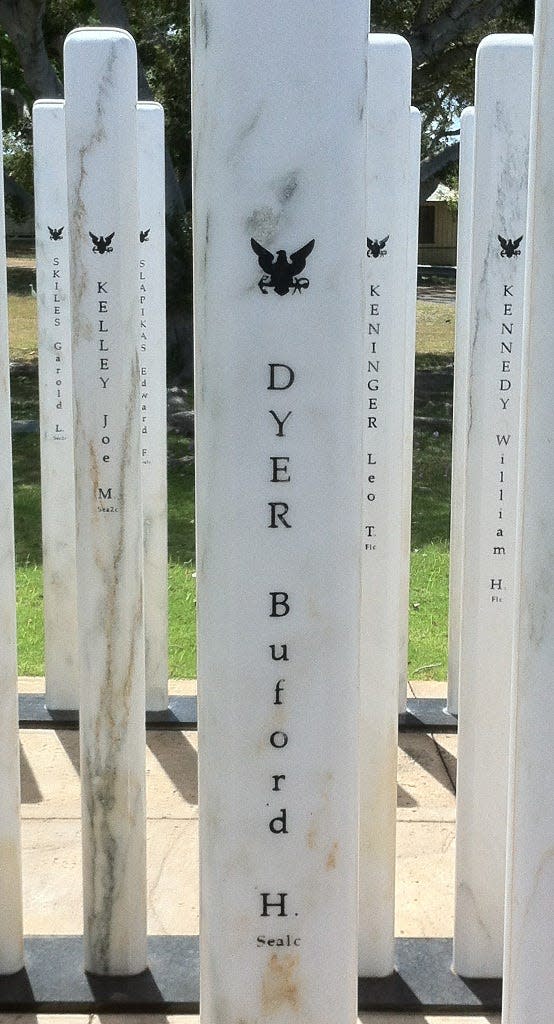

He is memorialized on the Tablets of the Missing at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Hawaii.

Dyer’s mother wasn’t informed of her son’s death until Feb. 17, 1942, and she was told he had been killed “somewhere in the Pacific.”

A newspaper account from March 1, 1942, related that Buford Dyer had written his mother days before the attack.

It was last time she heard from her oldest son.

Dyer’s remains were identified Aug. 5 this year, and he was the 350th crew member of the Oklahoma to be identified by The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency in a 6-year project dedicated to that task.

The remains of 33 sailors were unable to be identified, and they are to be reinterred Tuesday in Hawaii as part of memorial ceremonies.

"We sent these men and women off to combat and they have not returned home," said Kelly McKeague, director of the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, during a media videoconference Monday. "They are unreturned veterans. We have a sacred obligation, a moral imperative with which to do everything humanly possible to find them and to return them to their families."

Further advances in technology could mean they will be disinterred once more to help to identify those sets someday.

But most of the crew members who died that day have been identified, a feat once thought impossible.

Journey to identification can be tedious

The process of identifying remains, especially those as old as Dyer’s, is a high-tech, time-consuming task that requires the DNA of surviving family members.

More: Bob Dyer: DNA might bring World War II pilot home

Local resident Jay Musson is going through that process now in an effort to identify a relative who was a pilot in World War II.

Musson said DNA from three family members as required to identify his relative, and acquiring those samples was not easy.

The process started when someone from the U.S. Army contacted Musson about his relative. His DNA could be used, but tracking down two other family members and perrsading them to participate became a challenge. There were other relatives in Massachusetts, but they were not in a hurry to submit their samples, he said.

“It took six months to get these people to take the test and return it,” Musson said. “I got them to finally do it.”

Every 90 days, Musson said, he receives an update on the identification process. Second Lieutenant Ralph I. Musson served with the 91st Bombardment Squadron, and was involved in the Bataan Death March. He died from malaria in the Cabanatuan Prisoner of War Camp on the island of Luzon on June 30, 1942.

Musson said the experience of having a relative identified after so long led him to research his family history, especially that of Ralph Musson. Although Ralph Musson lived in Massachusetts before his time in the military, he spent vacations with his aunt, who lived in Akron.

Jay Musson served in the Vietnam War, thinking at times that he would not make it home, he said, and that helped create a connection with a family member he’d never met.

“It really hit me: Here’s a guy that’s been forgotten,” he said.

Although a final identification hasn’t been confirmed, Musson said he anticipates it will eventually happen.

"World War II was just so different from today," Musson said. "...There’s nobody to talk to, and the only thing left is records."

Barberton claims one of its own

Dyer’s story and tragic demise hit home with Barberton Mayor William Judge.

“A lot of these fallen heroes were teenagers,” Judge said Friday. “I don’t know if I would have been prepared to go to war at that age.”

On hearing the news about Buford Dyer’s identification and connection to Barberton, the mayor immediately wanted to find a way to honor him. Although details on Dyer’s arrival are still being worked out beyond the April 11 burial date, the mayor is hoping to organize an escort for the fallen sailor to his final destination at Western Reserve National Cemetery. That could include police and the VFW, he said.

“I’m thinking of painting the town red, white and blue,” the mayor said. “… There is great interest and willingness to do something.”

When Barberton resident Roger H Scritchfield heard that Dyer’s remains had been identified, he wanted to do something, too.

Scritchfield, a Vietnam War veteran, is a member of the Patriot Guard Riders, which provides escorts for funerals of members of the U.S. military.

“When you are in the service you have brothers, and now we have sisters,” he said. “The military is a family no matter how bad we liked it or how good we liked it.”

Scritchfield said when he returned home from Vietnam, the country had changed. Protests against the war included animosity toward returning veterans, many of whom were drafted and reluctant to join the military.

“The Vietnam veterans made a pact we would not let the stuff that happened to us when we came home ever happen to anyone else,” he said.

Scritchfield said the Patriot Guard escorts are open to motorcycle riders who have respect for the military and the escorted service member. American Legion and VFW members often join in the escort.

“The Patriot Guard does it, [but] everyone is invited to ride with us and it doesn’t have to be a motorcycle,” he said.

A message from a loved one

Dyer’s name is recorded on the Courts of the Missing at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu, along with the others missing from WWII.

Some details of his service are available on findagrave.com, and members of the site can leave flowers in his name. Messages to the deceased can be included.

Here is a note included with the gift of flowers from a relative Buford Dyer never got to know:

Dear Uncle Buford, For some reason, we were never to meet, but you have been in my life since I was able to understand Pearl Harbor and what it meant. Many tears have been shed in your honor and memory. My dad, your brother Jhugh, spoke of you fondly and always reminisced about your childhood. So you were always a part of my life if only in memories shared. My dad is now with you, so may you both rest in peace. Know that you have never been forgotten and never will be. I honor both you and my dad with the American flag that you both fought for so valiantly. With you always …

— April 16, 2015

Eighty years ago exactly, Navy Seaman 1st Class Buford H. Dyer became a part of U.S. and world history.

Although his immediate family never knew the closure that comes with identifying and burying the remains of a loved one, he is not forgotten.

Staff writer Krista S. Kano contributed to this report. Leave a message for Alan Ashworth at 330-996-3859 or email him at aashworth@gannett.com. Follow him on Twitter at @newsalanbeaconj.

This article originally appeared on Akron Beacon Journal: A Barberton sailor and his death on the USS Oklahoma at Pearl Harbor