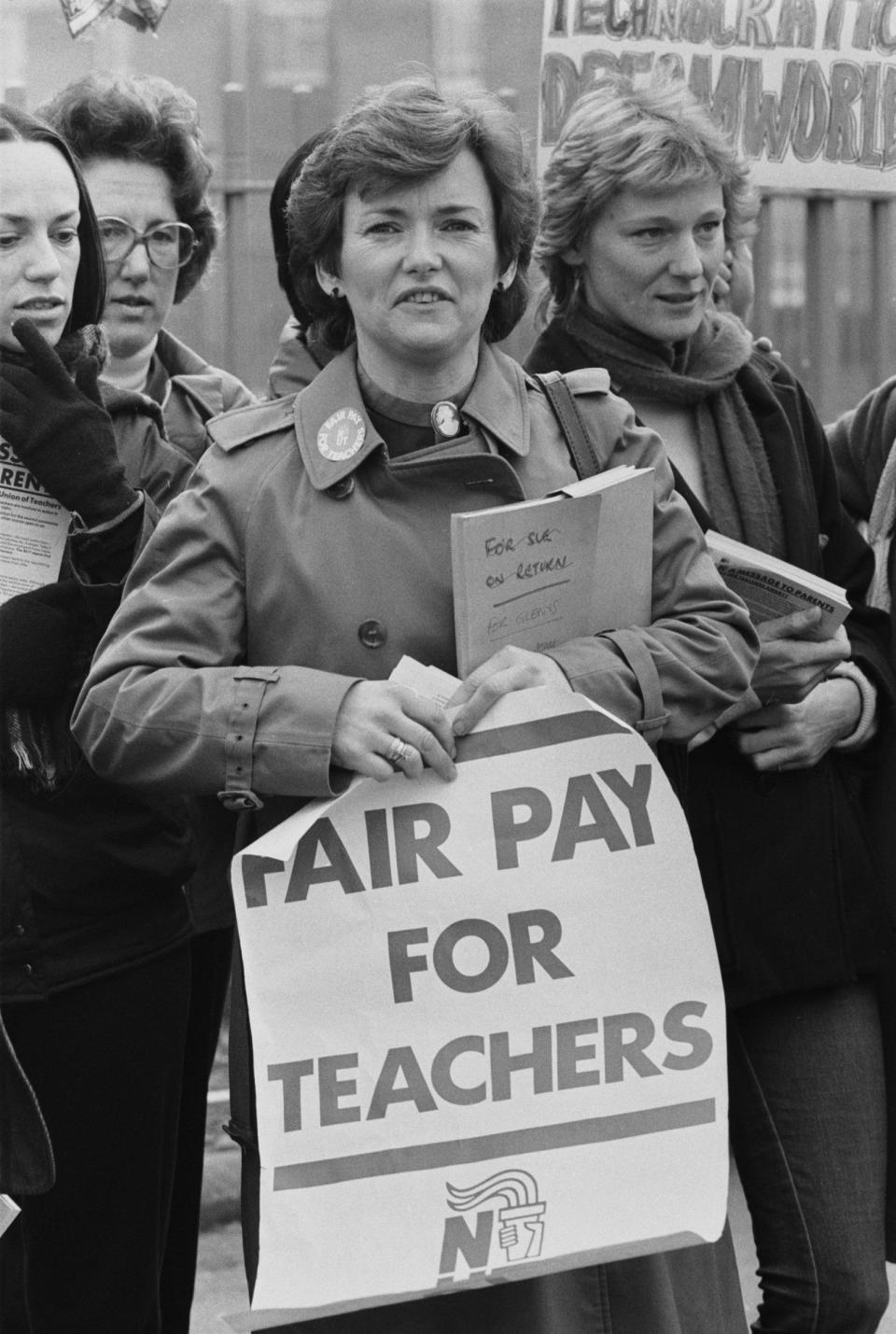

Glenys Kinnock, formidable wife of Neil who became an MEP and minister – obituary

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Baroness Kinnock of Holyhead, who has died of complications of Alzheimer’s disease aged 79, was the wife of Neil Kinnock, the Labour leader who became a European Commissioner, and a formidable member of the European Parliament, a Foreign Office minister under Gordon Brown and a high-profile campaigner for the developing world.

Elegant, radical and gregarious, Glenys Kinnock was the ideal consort for an ambitious but impulsive politician trying to revive a party that had alienated most of the electorate. Widely reckoned the brains behind her husband, she provided the driving force for his career and a secure family life, and he responded with lasting adoration.

Although they took almost every decision affecting him together – she even drove him to hospital for his vasectomy – both strenuously denied that she was Labour’s real leader. On the campaign trail and at party conferences she took a step back, but once elected an MEP in 1994 she showed her strengths, especially in campaigning to end poverty in sub-Saharan Africa.

During Neil Kinnock’s nine-year leadership which revived Labour’s fortunes but could not oust the Conservative government, Tory critics scorned his wife as an “eminence rouge”. She might have remained a “conscientious remedial teacher” living her political life through her husband had he not peaked so early; he was barely 50 when he gave up the leadership.

Almost uniquely for a political wife, Glenys Kinnock pursued an agenda of her own without embarrassing her husband. There were suspicions that she held him back from ditching Labour’s commitment to unilateral nuclear disarmament, but when Neil Kinnock let his CND membership lapse in 1991, so did she.

Nuclear disarmament had been her “life’s passion”. She joined CND at 16, before the Labour Party, and in the movement’s last flowering in the 1980s took a leading part in mass rallies and joined the “peace women” at Greenham Common. Her unilateralism tailed off into a moderate if persistent feminism.

Glenys Kinnock was a passionate opponent of apartheid. She refused a gold wedding ring lest the metal originate from South Africa. And when she paid the first of many visits to Africa with her husband in 1985, she made a point of visiting a school in Tanzania run by the then-outlawed African National Congress; The Daily Telegraph’s correspondent was excluded.

That same visit triggered her passionate concern for the developing world, when she met women who had walked for days to a hospital in Addis Ababa after childbirth had gone wrong. She went on to form the development lobbying group One World Action and play leading roles in War on Want – from which she resigned in protest at alleged financial mismanagement – and Unicef. She became a popular speaker at United Nations conferences on women’s and development issues.

Her campaigning against apartheid was rewarded in the election of Nelson Mandela as South Africa’s president in 1994, with the Kinnocks on hand as EU observers. She supported Nicaragua’s Left-wing Sandinistas with equal enthusiasm, only to see them eclipsed at the polls. Politically correct she may have been, but she moved with the times; Welsh Labour old-timers reproached her for shopping at Sainsbury’s instead of the Co-Op.

Glenys Kinnock shouldered with deep sadness but some style the defeats Labour suffered with her husband at the helm. That of 1987 was no surprise despite her sparkling performance on the campaign trail and in Hugh Hudson’s “Kinnock video” which briefly fuelled Labour euphoria; she held back from hiring a furniture van for the move to Downing Street.

John Major’s victory in 1992 was a shock, although she had never quite assumed Labour would win. She said the moment her husband conceded “was hard. I didn’t care about myself or anything else. I just felt for him.” But after a gloomy barbecue for his staff at their Ealing home, she helped him pick up the pieces.

Before long, Europe beckoned them both. Glenys Kinnock got there first, elected to the European Parliament for Wales South-East in 1994 by 124,247 votes, a record for a British election. Her husband’s subsequent appointment as a Commissioner meant their rebasing from London to Brussels, though always maintaining their ties with Wales and their interest in domestic politics. From 1999 she was one of the MEPs for Wales as a whole.

Co-opted to the parliament’s Development Committee, she urged a near 50-fold increase in EU development aid, and denounced human rights abuses in China, Nigeria, Rwanda and Burma, which she visited in mufti. She became vice-president of the African, Caribbean and Pacific/EU joint assembly.

Days after she left the Parliament in 2009, Gordon Brown appointed her Minister for Europe, with a life peerage. She held the portfolio for just four months, devoting much time to the unsuccessful campaign for Tony Blair to become the EU’s first president.

That October she took ministerial responsibility for Africa. Reunited with her favourite causes, she was particularly concerned at the Sudan’s disintegration into a renewed civil war. On Labour’s defeat in May 2010, she moved to the back benches.

Although she was the most loyal of wives, Glenys Kinnock considered her husband too much of a daredevil. His habit of persuading RAF pilots to take him into a power dive, or hanging out of aircraft dropping supplies to famine victims, led her to christen him “Biggles”. When he deserted her for the cockpit during one long-haul flight, she observed: “Neil wants to be a pilot when he grows up.”

Yet she was not above taking risks herself. Her narrowest scrape came in 2000 when she and the Conservative MEP John Corrie were among international mediators shot at in the Solomon Islands. Escaping, their aircraft attracted a hail of bullets. She remarked: “I heard a noise, but I didn’t know it was gunfire”; to Corrie it was “very hairy indeed”.

One frightening experience she shared with her husband: in 1988 when, arriving unannounced from Mozambique at a Zimbabwean air base, their entire party was locked in a tin hut by over-zealous security guards. Neil Kinnock gave the heavily-armed man in charge a dressing-down; a fawning apology from Robert Mugabe followed.

Glenys Elizabeth Parry was born at Roade, Northamptonshire, on July 7 1944. Her father, Cyril Parry, was a railway signalman and Labour activist who moved the family back to his native Holyhead when she was three. A Welsh speaker, she attended Holyhead High School before going to Cardiff University, where she met Neil Kinnock. Her first words to him were: “Are you the man from the Socialist Society?”

Their relationship had an unpromising start – she helped him home drunk from their first date – but they ran the society together for three years and she helped to engineer his election as Students’ Union president. Contemporaries named them “the power and the glory”.

She went on to teach in secondary, primary and special schools, first in South Wales and later in Brent, continuing part-time throughout her husband’s rise in the Labour Party. She also became an accomplished writer and broadcaster in support of her favourite causes.

When her husband’s successful “No” campaign against Welsh devolution in the late 1970s led extreme Nationalists to kick their front door in, she insisted they move with their young children to London. They settled in Kingston, then moved to Ealing to avoid the 11-plus, which they strongly opposed.

Glenys Kinnock founded One World Action (originally The Bernt Carlsson Trust) in 1989, after Carlsson, the UN’s Commissioner for Namibia, was killed in the Lockerbie disaster.

She was also a leading light in Saferworld, Drop the Debt, Parliamentarians for Global Action, the Burma Campaign UK, the Medical Foundation for the Victims of Torture, the National Deaf Children’s Society, the International Aids Vaccine Initiative, the National Breast Cancer Coalition, Crusaid, the Elizabeth Hardie Ferguson Trust, VSO, Britain in Europe and the British Humanist Association.

She was president of Coleg Harlech, and vice-president of the University College of Wales, Cardiff from 1988 to 1995. Her husband received his life peerage in 2005; she retired from the Lords in 2021.

Married in 1967, the Kinnocks had a son – Stephen Kinnock MP, married to the former Danish prime minister Helle Thorning-Schmidt – and a daughter, Rachel.

Glenys Kinnock, born July 7 1944, died December 3 2023