Barry Garron, longtime critic who wrote about TV and radio for The Star, dies at 72

On August 9, 1990, Barry Garron placed a container of homemade chocolate chip cookies in his car, trekked out across rural Kansas and presented them to Christopher Walken.

It was a side quest The Star’s then-television critic happily took on for a friend and colleague who was a big fan of the Hollywood star. Garron was traveling to meet Walken and Glenn Close for interviews in Melvern Lake, roughly 100 miles southwest of Kansas City, on the set of the made-for-TV movie “Sarah, Plain and Tall,” a Hallmark production based on an award-winning children’s book.

“Anybody else, I wouldn’t have asked. Because they would have thought it was crazy,” said Dru Sefton, a friend and former Star copy editor, who asked Garron to make the delivery on her behalf. “But, of course, Barry said, ‘Well, of course I’ll bring him cookies for you.’

“That was Barry,” she added. “I feel so honored and lucky to have been able to work with him because he was one of a kind. He was a gem.”

A celebrated journalist who cut his teeth at The Star and spent nearly a quarter-century here, Garron was known professionally as a well-sourced Hollywood reporter and, for a time, president of the TV Critics Association, with a vast knowledge of television and its industry.

On Thursday morning, Garron died in a rehabilitation facility in suburban Phoenix, where he moved from Los Angeles six years ago, after long battling with illnesses, according to family. He was 72.

Born on Sept. 2, 1949, in Chicago, Garron grew up in the residential Rogers Park neighborhood on the northern edge of the city. He began his journalism career as a young man at University of Illinois-Chicago, where during his freshman year he started working for the student-led publication, his brother David Garron, 75, said.

“He enjoyed it so much that he said he wanted to pursue a career in journalism,” the elder Garron recalled, adding: “He enjoys writing and he’s a very good writer. Anybody that plays a word game with him is going to lose.”

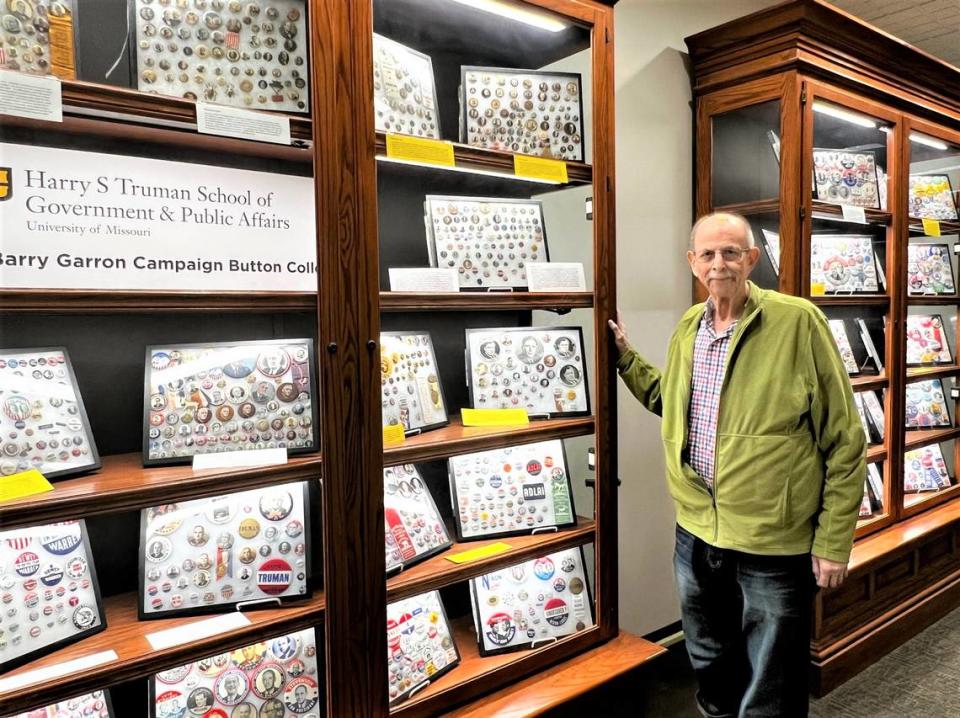

The following year, Garron transferred to the University of Missouri-Columbia, where he earned degrees in political science and journalism in 1971. He also had a passion for politics, his brother said, and amassed a large collection of presidential campaign pins, which he donated to Mizzou. It was named after him and his late wife, Sandi Garron.

Early stops along his career path included stints in Columbia and upstate New York. In 1973, Garron joined the ranks of The Star, first as an education reporter, and when the opportunity arose to become the paper’s TV and radio critic, he took it.

Though he hailed from Chicago, Kansas City became his home for much of his adult life, his brother recalled. Growing up the brothers worked as vendors at the old Comiskey Park, where the White Sox played, but the younger Garron adopted the Royals as his favorite baseball team when he moved here. It was also where he married his wife, Sandi Garron, and where the pair raised their only daughter, Rachel.

As a writer for The Star, Garron shared the news of all the big television series that were coming to the living room screen, often spending hours watching bad shows so others didn’t have to. He was known to produce snappy headlines as he picked winners and losers from a Kansas City point of view.

Also on display were his quick wit and, sometimes, a dry sense of humor. Regarding the “Sarah, Plain and Tall” movie starring Walken and Close, for example, Garron wrote that one could argue Close was neither “plain nor tall” and noted Walken, known at the time for portraying “psychotics and villains,” was now playing “a warm and caring father.”

“Here, amid the prairie grass, the flies and the chiggers, Glenn Close and Christoper Walken have been acting in a tender story about love and loneliness,” Garron wrote in his report.

Though he enjoyed doing it, the job was one he took quite seriously, evidenced in part by a vault-like collection of tapes he received from studios for reviews that he kept in his suburban Kansas City home, said Robert Butler, another former Star reporter, who recalled seeing Garron’s setup in the 1980s.

“He had this world-class collection of all the first episodes of all these TV series literally filling his basement,” Butler said, adding: “He took television seriously and he saw that VCR tape as a bit of history. It was an important document in his line of work.”

In 1997, Garron left The Star and moved to L.A., a place he had already spent a lot of time, joining The Hollywood Reporter as its chief critic. He had that job until 2006, he said in an alumni interview with Mizzou, then continued until recently to work as a freelance reporter, including for The Hollywood Reporter.

Despite moving out west years ago, Garron’s connection to and memories of Kansas City never faded, his brother said. Only last month the pair were in town seeing the sights, including a stop by the newspaper’s old office building downtown.

For the friends he made here, the memory of Garron never faded either.

On that day back in 1990, after his trip to the Kansas movie set, Garron made a second delivery — to his friend and colleague Sefton. It was a note with a brief message, signed “Chris Walken,” that she still keeps to this day.

“Thanks for the cookies,” it read.

In addition to his brother David, Garron is survived by his daughter Rachel Dain and son-in-law David Dain; sister-in-law Myrna Garron; grandchildren Sierra Dain and Alisa Dain; and his dear friend Gloria Laurent, with whom he lived for many years. Services and a memorial were being arranged to be held in early July in Phoenix.