New Baseball Hall of Fame member was first pro Black player. And he played in Galesburg.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Editor's note: This story was originally published in 2021. We are republishing it ahead of Bud Fowler's Hall of Fame induction on Sunday.

One of newest inductees into the National Baseball Hall of Fame was a second baseman/outfielder for a Galesburg a minor league team that in 1890 played its games at Willard Field on the Knox College campus.

His name was Bud Fowler, and he's recognized as the first professional Black ballplayer.

Fowler joins Buck O’Neil, Gil Hodges, Minnie Miñoso, Tony Oliva and Jim Kaat as the new baseball hall of famers as chosen by a pair of veterans committees on Dec. 5. The six newcomers will be enshrined in Cooperstown, New York, on July 24, 2022, along with any new members elected by the Baseball Writers’ Association of America.

This was the first time Fowler, O’Neil and Miñoso had a chance to make the Hall under new rules honoring Negro League contributions. Last December, the statistics of some 3,400 players were added to Major League Baseball’s record books when MLB said it was “correcting a longtime oversight in the game’s history” and reclassifying the Negro Leagues as a major league.

More: How Bud Fowler's Hall of Fame baseball career was ruined after racist revolt in Binghamton

Fowler played with numerous minor-league clubs over two decades, including the 1890 season in Galesburg. He played for more clubs and in more games in the minors than any other Black player before the 1950s, hitting .308 in more than 2,000 at bats in organized baseball.

Minor league baseball started in Galesburg in 1890, and Fowler — who was nearing the end of his professional baseball career — played in two different stints for Galesburg teams that season.

As a member of the Galesburg team in the Central Interstate League, Fowler played in 27 games, hitting .322 with six doubles, three triples a pair of home runs and seven stolen bases. According to Baseball Reference, the Central Interstate League in 1890 consisted of the following teams: from Burlington Hawkeyes, Evansville Hoosiers, Galesburg/Indianapolis, Peoria Canaries, Quincy Ravens and Terre Haute.

The team disbanded, but reformed as a Sterling/Galesburg/Burlington (Iowa) team in the Illinois-Iowa League later in 1890. In 36 games, Fowler played in 36 games, hitting .314 with 11 doubles, a pair of triples and 14 stolen bases. According to Baseball Reference, the Illinois-Iowa League in 1890 consisted of the following teams: Aurora, Cedar Rapids, Dubuque, Joliet, Monmouth, Ottawa, Ottumwa and Sterling/Galesburg/Burlington.

Fowler's induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame was especially satisfying for many baseball historians, including Joe Williams, co-chair of the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR's) Overlooked 19th Century Base Ball Legends Committee.

"The evolution and growth of both 19th century baseball research and Black baseball research shed light on Fowler's importance to the history of the game," Williams said in an interview with The Register-Mail.

"First, as being the first Black ballplayer in professional organized baseball, and then for his play over his career and the several roles he played in organizing clubs and leagues. He was a pioneer and trailblazer. You cannot tell the history of baseball without Bud."

Fowler joins Grover Cleveland Alexander (1909) and Sam Rice (1912) as baseball hall of famers who got starts playing minor league baseball for Galesburg teams.

In his 2013 book "Bud Fowler: Baseball's First Black Professional," Jeffrey Michael Laing described how Fowler ended up in Galesburg.

After spending the winter of 1889-90 in Toledo, Bud Fowler signed with Evansville (Indiana), but his contract was sold before the season to Galesburg (Illinois) of the Central Interstate League. Since the Illinois club was using an infusion of $1,000 or more to boost civic morale, management pursued the African-American infielder in a manner that reflected the community’s desire to have a first-rate ball club: “Second baseman Fowler, who has been wintering in this city (Toledo), has joined the Galesburg, Ill., team. Galesburg purchased his release from Evansville, paying $500, Fowler getting a share of the purchase money.”

Brian McKenna of SABR offered this insight on Fowler's 1890 season in Galesburg.

He hit well for the club, batting .322 in 27 games. On May 2 in Galesburg’s home opener, Bud knocked six hits in seven at-bats, scoring five times in a 31-5 win over Peoria. Three days earlier, he knocked a home run “which created a good deal of enthusiasm.” The Sporting Life noted, “The visiting club fielders move back when Taylor, Al Weddige and Fowler go to the bat.” Galesburg disbanded around the turn of June and Fowler caught on with Sterling (Illinois) of the Illinois-Iowa League during all of July.

After his first game with the club on July 1, the Sterling Evening Gazette couldn’t contain its delight in having the new player: “Our new second baseman, Fowler, caught the crowd by his field work, and put-up the finest game at second (base) ever seen here. … Fowler ran out into center twice and took flies away from (center fielder) McCann to the latter’s disgust, but in the eighth made the play of the year by going back of short and getting a fly which made the third out and saved two runs from going over the plate. He must have run 120 feet and the crowd gave him a big recognition of the successful effort.” Fowler rejoined Galesburg in August, now refinanced and reorganized in the IIL, and finished with Burlington (Iowa) through franchise relocation in the IIL. In 36 games in that league he hit .314.

Laing wrote in his book that as the country suffered through a deepening economic crisis and segregation became the accepted social order, Fowler found his opportunities to play in integrated organized baseball severely curtailed after the 1890 season.

Baseball Reference reports Fowler's career spanned from 1878 to 1895.

"Fowler's time in Galesburg was brief like many of his stops over his long career," Williams said. "His time with the team showed he was a star player and his April 30th home run that "created a good deal of enthusiasm" proves that not everyone in attendance was against a Black ballplayer playing with white ballplayers."

Born John W. Jackson Jr. in Fort Plain, New York, on March 16, 1858, Fowler’s family moved to Cooperstown — located about a half hour from Fort Plain — just a few years later. According to village historian Hugh MacDougall, just 28 Black people lived in Cooperstown at that time, and Fowler attended school primarily alongside white children. His father was a barber and in later years Fowler followed in his footsteps to help supplement his income.

McKenna noted Fowler's nickname was "Bud" because that’s how he referred to everyone.

Forever Legends.

Minnie Miñoso. Buck O'Neil. Bud Fowler.

Congratulations on being inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame! pic.twitter.com/cChV8rRbSZ— Negro Leagues Baseball Museum (@NLBMuseumKC) December 6, 2021

Fowler's player profile on the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum website explains how he was able to play for so many years.

In the early days of baseball there was no official color line, and he played in organized baseball with white ball clubs until the color line became established and entrenched. However, his stays were almost always of short duration despite his playing ability-probably because of the race factor. In 1887 he was dropped from Binghamton of the International League and was forbidden to sign with another International League team.

The profile went on to say:

In 1909, with Fowler in failing health, several attempts were made to play a benefit game for the ailing baseballist, but the efforts all proved unfruitful and the game never materialized. Less than three years later, the "real first” Black professional baseball player died of pernicious anemia after an extended illness, just eighteen days short of his fifty-fifth birthday.

In August 1893, he again played in Galesburg, this time for an independent team under manager Belden Hill.

“I am not surprised that Fowler made his way through Galesburg and the region," said Raymond Doswell, vice president/curator of Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, and a 1990 graduate of Monmouth College. "He traveled extensively across the country as a talented, sought after player.

"There were Black and white players like Fowler who would play short stints and partial seasons for many amateur or minor league teams in the early part of the 1900s. Historians have credited him as the ‘first Black professional’ player, noting the transition in the sport from amateurism to professionalism on regional teams looking for the best talent.

"In an age of segregation, Fowler proved his athletic value through his travels, starting for black and white teams. His success ultimately set the stage for all Black professional teams and the eventual establishment of the Negro Leagues.”

More: Raymond Doswell to discuss Negro baseball leagues

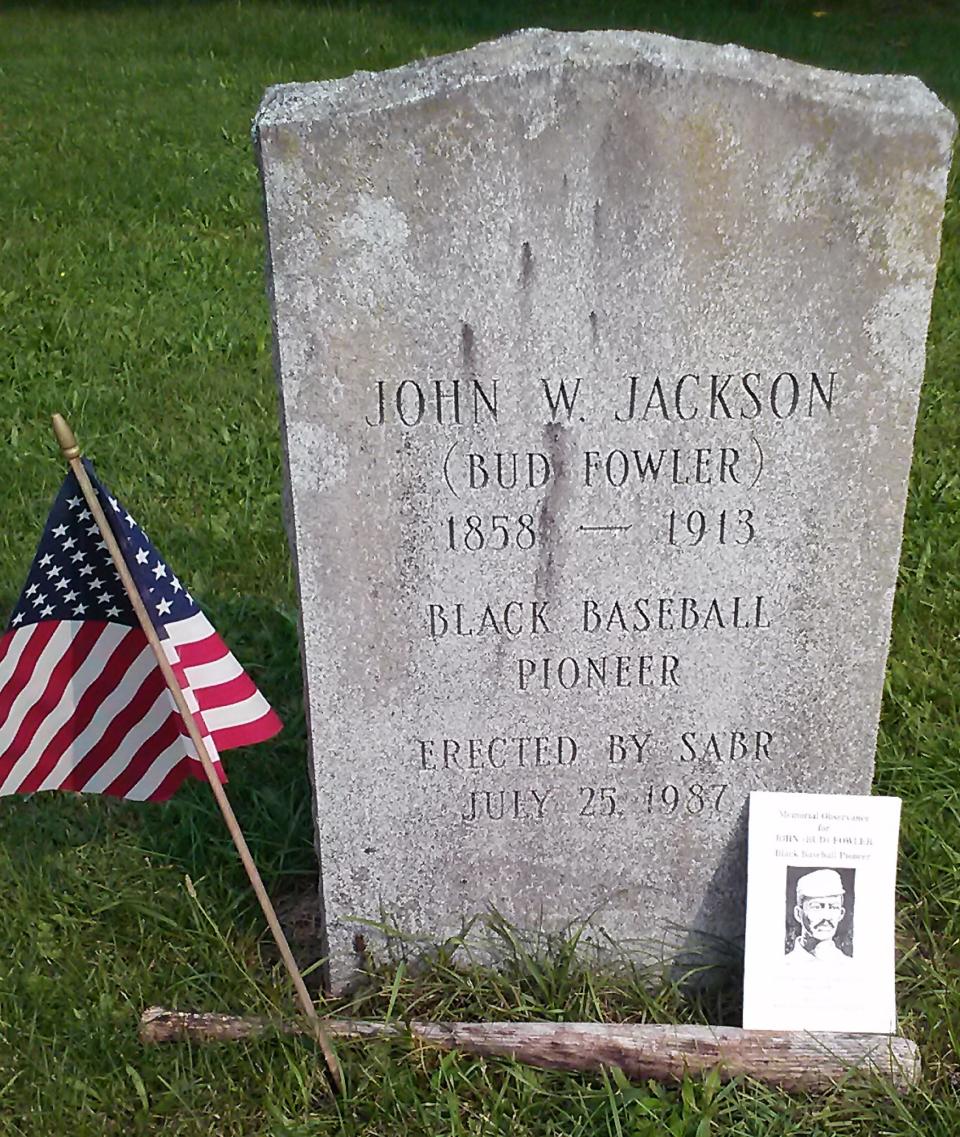

His grave in Frankfort, New York, went unmarked until the Society for American Baseball Research placed a memorial there in 1987.

"Fowler's election was long overdue, but it no longer matters because he is finally a Hall of Famer," Williams said. "When I visited his grave in 2016 I promised him he would be a Hall of Famer and that is now a reality. I look forward to seeing his plaque on July 24, 2022, after the induction ceremony."

Bud Fowler’s Cooperstown ties run deep: He grew up in the village and was honored in 2013 when the street leading to Doubleday Field was dedicated as “Bud Fowler Way.”

Now, he’ll take his place in the Hall of Fame.https://t.co/9ItPS5VqMZ | 📷: Milo Stewart Jr. pic.twitter.com/z9fRJ7qGgl— National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum ⚾ (@baseballhall) December 6, 2021

Here's what others are saying or have said about Fowler:

"Only the Ball Was White," 1970, by Robert Peterson. For the next 25 years (after his debut in 1878), Fowler barnstormed around the country, from Massachusetts to Colorado, playing wherever (Black) players were permitted. He played in crossroads farm towns and in mining camps, in the pioneer settlements of the West and in the cities of the East. These were the years of growth for the minor leagues, the foundation stones for organized baseball, and Fowler performed in several of them. He was the first of more than 60 (Black players) who were in white leagues before the turn of the century, when baseball’s leaders began to think of their structure as organized baseball in capital letters and when the long night of total exclusion lowered for the Black man.

Jay Jaffe, FanGraphs: Bud Fowler was Black baseball’s original pioneer, its first acknowledged professional, with a career that’s believed to have spanned from 1878 to 1904. An exceptional hitter, pitcher, and fielder who could play any position (sometimes catcher, but mainly second base), the 5-foot-7, 155-pound righty was believed to be of major league star quality, and is recorded as having hit .308 in over 2,000 at-bats in 10 seasons of organized baseball. Alas, the color of his skin and the prejudice that followed prevented him from ascending to the majors. Playing on integrated teams before the color line was fully entrenched — even captaining some — he traveled a hard road, unable to stay in one place for long before the objections of teammates or opponents forced him to move on, even given his considerable talents; by his own count, he played in 22 different states plus Canada. In the latter stages of his career he became one of the game’s first significant Black promoters, involved in forming leagues and teams.

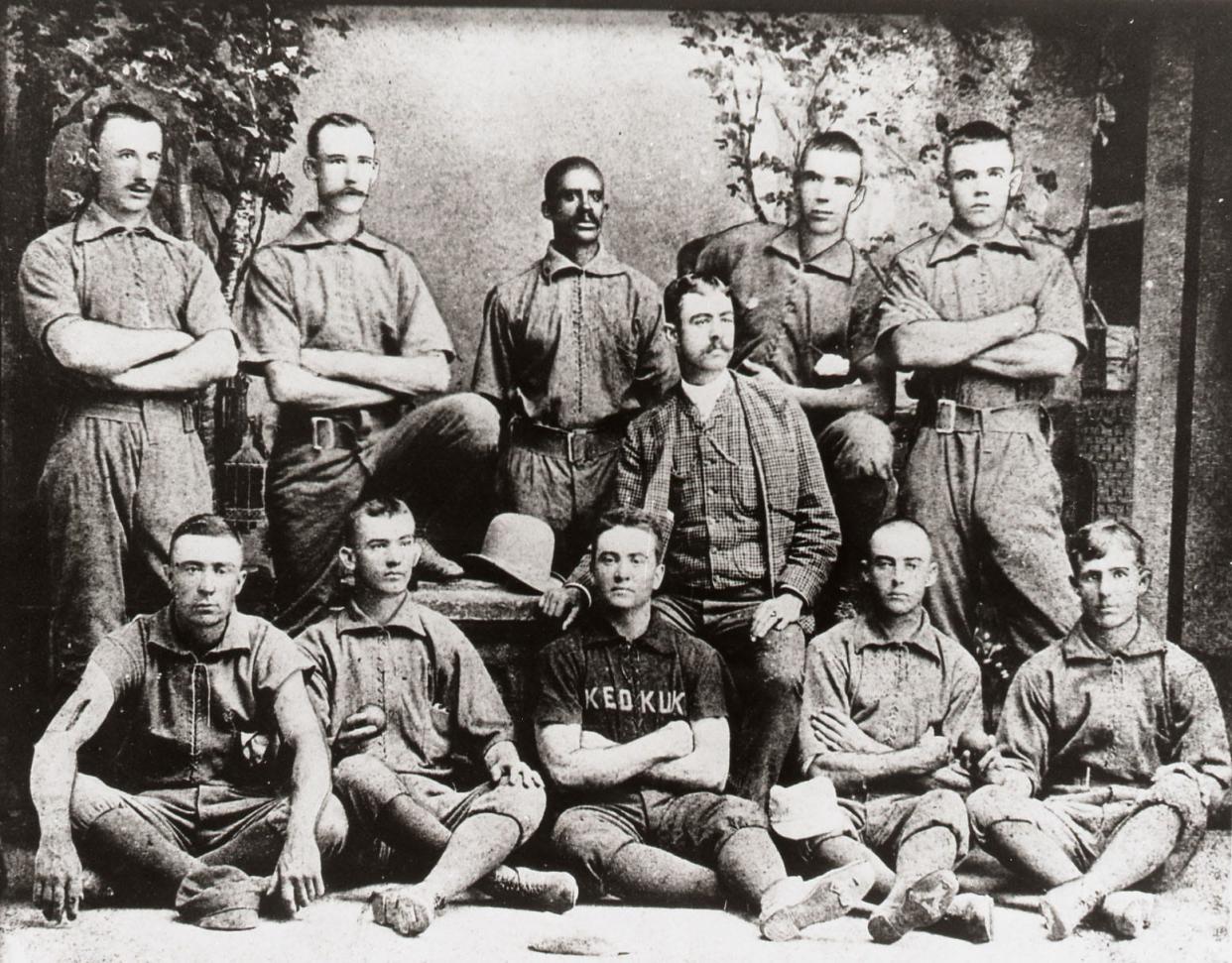

National Baseball Hall of Fame: The color of Fowler’s skin forced him into a more nomadic career than his white contemporaries. He manned second base for the Keokuk Hawkeyes in Iowa, appeared in the Colorado State League, signed with the Topeka Capitals, returned east to star for the Binghamton Crickets, ventured to Indiana to play for the Terre Haute Hoosiers, traveled Southwest to join the New Mexico League, represented Greenville in the Michigan State League and led the Nebraska State League in steals. All told, historians estimate he played for more than a dozen leagues throughout the course of his career, while Fowler himself claimed to have played on teams “based in twenty-two different states and in Canada.”

“For 16 years he was a pitcher and for 12 years a second baseman, and he never wore a glove, taking everything that came his way with bare hands. He was considered the equal of any man who ever covered the position,” wrote the Berkshire Eagle in 1909.

Benjamin Hoffman, New York Times: Words like “pioneer” and “trailblazer” are often used to describe Fowler, and on (Dec. 5) he added a new title: Hall of Famer. Fowler is part of a six-person class that was elected by a pair of committees asked to review players from baseball’s past. Of the six players, he has the least name recognition, but his exclusion has long been viewed as a mistake by baseball historians.

While Buck O’Neil, a player and manager for the Kansas City Monarchs, and Minnie Miñoso, who played for the New York Cubans at the start of his career, were the first players from the Negro leagues to be elected to the Hall of Fame since 2006 — and the first to be elected since several Negro leagues were recognized by Major League Baseball last year as having been major leagues — Fowler’s career predated most of those organized Negro leagues. Much of it came before the white major and minor leagues effectively barred Black players in the late 1880s.

This article originally appeared on Galesburg Register-Mail: New Baseball Hall of Fame member was first pro Black player. Played in Galesburg.