When baseball returns to Hinchliffe Stadium, players will retrace steps of legends

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When baseball returns to Hinchliffe Stadium in May, players will be retracing the steps of legends.

The newly restored stadium above Paterson's Great Falls is one of only a few venues that remain from baseball's Negro Leagues era. Exceedingly rare, Hinchliffe is the only stadium that served as a regular home field for a Negro Leagues team left in the Northeast.

The New York Black Yankees played at Hinchliffe for 12 seasons. The New York Cubans played there for two.

Hinchliffe is where the Newark Eagles gave Paterson's adopted son, Larry Doby, a 1942 tryout that helped propel him through the American League's color barrier. It was also where Doby made his name as a teenager playing semipro ball for the Furrey Smart Sets, an all-Black team sponsored by local real estate developer William P. Furrey.

The stadium is a national historic landmark, a rarer designation than Boston's Fenway Park with its place on the federal list of “National Historic Places." Named a landmark in 2013, before work started to revive it, Hinchliffe is also the only baseball stadium in the National Park system.

It has unparalleled lore, with dozens of legends having taken its field.

"There are over 20 Hall of Famers that played at Hinchliffe Stadium," said Brian LoPinto of the Friends of Hinchliffe Stadium. "That says to me that there's a piece of Cooperstown in Paterson."

Story continues below photo gallery.

The best to ever play there was Josh Gibson, LoPinto said, citing a mirroring claim from Doby. The so-called "Black Babe Ruth," Gibson led the Negro National League in runs batted in more often than not. Hinchliffe also hosted his Pittsburgh Crawfords teammates Oscar Charleston, whom Baseball Reference statisticians credit with the second highest career batting average of all time behind Ty Cobb, and James "Cool Papa" Bell, who was by many accounts, the fastest player in the Negro Leagues.

“One time he hit a line drive right past my ear. I turned around and saw the ball hit him sliding into second," Negro Leagues legend Satchel Paige said about Bell, according to Baseball Hall of Fame records.

The list of players in the Hall of Fame who graced Hinchliffe goes on. It includes Martin Dihigo, who is in five national Baseball Halls of Fame, Monte Irvin, Ray Brown, Hilton Smith, Roy Campanella, William "Judy" Johnson, Walter “Buck” Leonard, and Jay "Dizzy" Dean. Dean barnstormed Hinchliffe with his brother Daffy in October 1934 fresh off a World Series win and National League MVP honors.

There are other big names with memorable nicknames: John Henry "Pop" Lloyd, aka “El Cuchara,” Ray "Squatty" Dandridge, Ted "Double Duty" Radcliffe, "Bullet" Joe Rogan, Normal "Turkey" Stearnes, George "Mule" Suttles, Horacio “Rabbit” Martinez and Juan “Tetelo” Vargas, who won the 1943 Negro National League batting title with a .471 average. It is the highest single-season average of all time, according to Baseball Reference.

Fats Jenkins didn't need a nickname. Perhaps the most unheralded two-sport athlete of all time, Jenkins was a high-average leadoff hitter and rangy center fielder for the Black Yankees and others. He was also a star point guard for the New York Renaissance, who in 2021 was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.

Hinchliffe was a stage for some of the best players from the United States and Caribbean in its heyday, but it also held hometown heroes. Madison native Don Newcombe played there for the Newark Eagles before becoming the first Black pitcher to start a World Series game in 1949 and winning the inaugural Cy Young Award along with a National League MVP in 1956. Irvin was born in Alabama but was a four-sport star at Orange High School. Doby, another barrier breaker, moved to Paterson from South Carolina at 14.

A standout athlete at Eastside High School, Doby played both high school baseball and football at Hinchliffe. He was a dynamic pass catcher and runner, according to newspaper reports, but was even better on the baseball diamond. Bob Whiting, a sports columnist for The Paterson Morning Call at the time, named Doby "the best prospect on all the local sandlots" in the summer before Doby's senior year of high school. Later in 1941, The Paterson Evening News called him the standout of the Bergen-Passaic semipro baseball league.

"Unfortunately as far as his big league aspirations are concerned, Doby is colored and will never be given a chance to break into organized ball," Whiting wrote.

Doby played well enough for the Smart Sets to catch the attention of the staff from the Newark Eagles, the stadium's part-time occupants from the National Negro League. Five years later, Bill Veeck, a team owner buoyed by the Brooklyn Dodgers' signing of Jackie Robinson, sealed Doby's place in history. Doby joined Major League Baseball's Cleveland franchise in July 1947, just weeks after Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier. Doby, then 23, became the first Black player in the American League.

Robinson also made history in New Jersey by playing his first game for the Dodgers’ AAA farm team in Jersey City’s Roosevelt Stadium. That stadium was destroyed in 1985. Ruppert Stadium in Newark, where Doby and the Eagles played most home games, was razed in 1967. Princeton's Palmer Stadium, where Jesse Owens held the long-jump record, is also gone. Hinchliffe is the only major athletic stadium in New Jersey that predates World War II.

Hinchliffe barely survived. It fell into disrepair in the 1990s and was condemned in 1997 under the ownership of the local school board, whose public ownership combined with community support for the stadium's preservation kept redevelopment at bay. It wasn't destroyed, but it wasn't maintained. For years, Hinchliffe faded. LoPinto and others, meanwhile, helped spread awareness of the plight in a quest to secure funding for its restoration.

In 2010, the stadium made the National Trust for Historic Preservation's list of America's 11 Most Endangered Historic Places. Three years later, it was named a National Historic Landmark. Since, grants have helped stabilize it. Baye Adofo-Wilson, former Newark deputy mayor, had led the charge to bring it back as co-developer of a $100-million revitalization project in and around Paterson Great Falls National Historic Park.

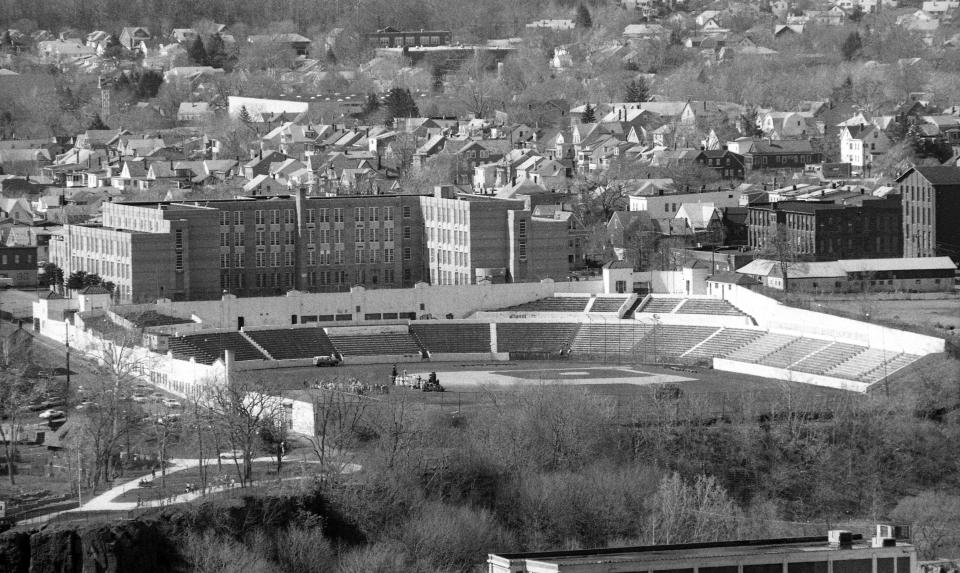

Newly renovated to fit roughly 7,800 fans and host New Jersey Jackals home games starting May 20, the stadium first opened on July 8, 1932. Designed by local architect John Shaw based on plans developed by the Olmsted Brothers landscape architectural firm, it features cast concrete stands set into natural slopes. Shaw's firm was an easy pick for city officials, having previously designed Central and Eastside high schools. The Olmsted Brothers firm had been heavily involved in the development of Passaic County's park system.

Records of organized baseball in Paterson date to the 1850s. Honus Wagner famously represented the Paterson Silk Weavers of the Atlantic League at the end of the 19th century. The Paterson Silk Sox arrived in the 1920s. All the while, the city's teams went without a true stadium of their own. Typically, they played in Clifton. Mayor John V. Hinchliffe would help change that.

Pursuing a multi-sport stadium soon after taking office, Hinchliffe first pitched a site near Totowa. Political pressure led him to pivot, and temporary stands instead went up on the city's Monument Heights site, a cemetery turned park overlooking the historic mill district of east Paterson. It was a trial run for a permanent stadium. It was also a hit. A reported crowd of roughly 12,000 came to witness Central play Eastside in football on Thanksgiving 1930, according to newspaper reports. A few months later, the mayor announced plans for a permanent enclosure. Voters subsequently backed a $217,000 bond issue in spite of the Great Depression.

"There is every reason to believe that the stadium will ultimately be a paying investment financially for the city," Hinchliffe said in his annual mayor's message for 1931. "But the main thing is that we are to have a stadium that will stimulate interest in athletic events and give us a standing in the athletic world even higher than we have now."

Construction started in November 1931 and finished the following June, according to National Parks Service records. The new stadium fit roughly 11,500 but in many ways was similar to the much larger home of baseball's New York Giants, the Polo Grounds. It featured an oblong, horseshoe (or umbrella-handle) shape with a deep outfield and rounded corners. "Hinchliffe City Stadium," named more for the mayor's uncle and former Paterson Mayor John Hinchliffe, quickly became the place to see many of the great African American and Latino players of the era.

"There weren't that many African Americans living in Paterson, yet there was great support for Black baseball," LoPinto said. "That tells me it was about the game, not so much about the color of someone's skin."

The schedule would go far beyond baseball, as promised by Hinchliffe. Boxing was especially big. Jack Dempsey and Joe Louis, literal and figurative boxing heavyweights, would guest referee there in 1943 and 1949, respectively. The state's first sports telecast was captured at Hinchliffe during the 1946 Diamond Gloves championships. Six years earlier, city native and legendary trainer Lou Duva won a Diamond Gloves championship there in the novice welterweight division.

A blend of Spanish Colonial Revival and Art Deco styles, the stadium was designed to prioritize baseball. Still, it was billed as a multi-purpose venue. Football teams, such as the Paterson Panthers, Paterson Giants, Paterson Nighthawks and Silk City Bears, played at the stadium in its opening year, according to National Park Service records. In 1933, Hinchliffe was the site of a silk industry workers' rally. Through the early 1950s, cars and motorcycles regularly raced around a 1/5th-mile oval inside its stands.

There were rodeos, pro wrestling events and soccer games at Hinchliffe. Asbury Park's Bud Abbott and his comedy partner Lou Costello of Paterson performed there, as did Sly and the Family Stone, Duke Ellington and KRS-One.

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Hinchliffe Stadium is where baseball legends once played