Bass anglers in Georgia might be surprised to learn where their catch originated

Correction: This story has been updated to reflect how DNR employees extract eggs from female fish, and the size of the fish when they are sent to other hatcheries.

Georgia's rivers and estuaries are filled with fish of all sizes and colors from giant sturgeons to little minnows. But what many Georgia anglers may not realize is that while their favorite fish live in the state's rivers and lakes, that may not be where they came from.

During the spring season, Georgia Department of Natural Resources-operated hatcheries throughout the state spawned millions of fish popular with Georgia anglers to ensure stable populations in the state's rivers, lakes and ponds. Each hatchery has a couple of species it specializes in and works within the network of hatcheries to send fish all over to grow up and ship out to bodies of water for stocking.

For Atlantic striped bass, hybrid striped bass and white bass, each fish gets its start in the same place, at the Richmond Hill fish hatchery just off Highway 17 near Savannah.

At the lake: Access to day-use area at Thurmond Lake closed to a sinkhole

More fishery management news: Shrimpers and scientists collaborate to study parasite worsened by climate change

A system of support

There are several reasons natural production isn't sustainable for these type of bass. Along with humans fishing, habitat degradation from pollution, disturbances, development, poor water quality and damming can cause fish to spawn fewer offspring. Some watersheds, like the Savannah River, also have predators that can cut down local rates of reproduction.

For a sustainable population, and ample opportunity for the state's anglers, the DNR stocks fish to keep populations at healthy levels.

The Richmond Hill hatchery has been raising striped bass in Georgia since the 1960s. The hatchery's fisheries biologist, Alex Cummins, said through trial and error they've found that the Oostenala River, a tributary of the Coosa River near Rome, Georgia has the striped bass — also known as "stripers" — which produce the most young.

Spring is the boom season for the hatchery's work, according to Cummins. There is a tight window for spawning and for many species, just two days' worth of spawning fulfills the DNR's stocking goals for the entire year. The bulk of the springtime isn't handling adult fish and working with eggs, but waiting for the fry to get large enough to ship off to grow even larger in other hatcheries or to send to their final bodies of water in the wild.

The entire inland population of Atlantic striped bass and the hybrid bass, which do not reproduce naturally, are dependent on the Richmond Hill hatchery.

Environment at the capitol: See which environmental bills in the Georgia General Assembly won't become law

Bird news: Georgia's elusive nocturnal bird: conservationists' search for the chuck-will's-widow

From hatchery to water, fish provide lifelong passion for anglers

"I became obsessed with stripers about 10 years ago," said Pete Semaan. He runs Blue Water Charter Co., taking anglers on inshore fishing trips in coastal Georgia. But on his own time, he's all about stripers.

Despite knowing of the Richmond Hill hatchery, he had no idea his favorite fish were all spawned nearby. He's spent years near-obsessively pursuing his passion for stripers in local waters. At one point when he first started he said he fished the Ogeechee River sometimes three times a week for the striped bass, the one watershed in the state that Cummins said that stripers do repopulate naturally.

"There's just something about when they hit that lure, it's such a hard hit and a hard fight," Semaan said. "If I went all day and only caught one it was a huge success."

And for him, that was part of the allure. Semaan said that he found stripers to be elusive and he's never quite figured them out. It tested his skills, making him try different strategies and tactics to reel in the catch.

When you hold them up to the sun, Semaan said they shine blue and green with bold lines on their side. They are beautiful and strong, and Semaan said he has immense love and admiration for the fish.

How it's made: a look into fertilization and hatching

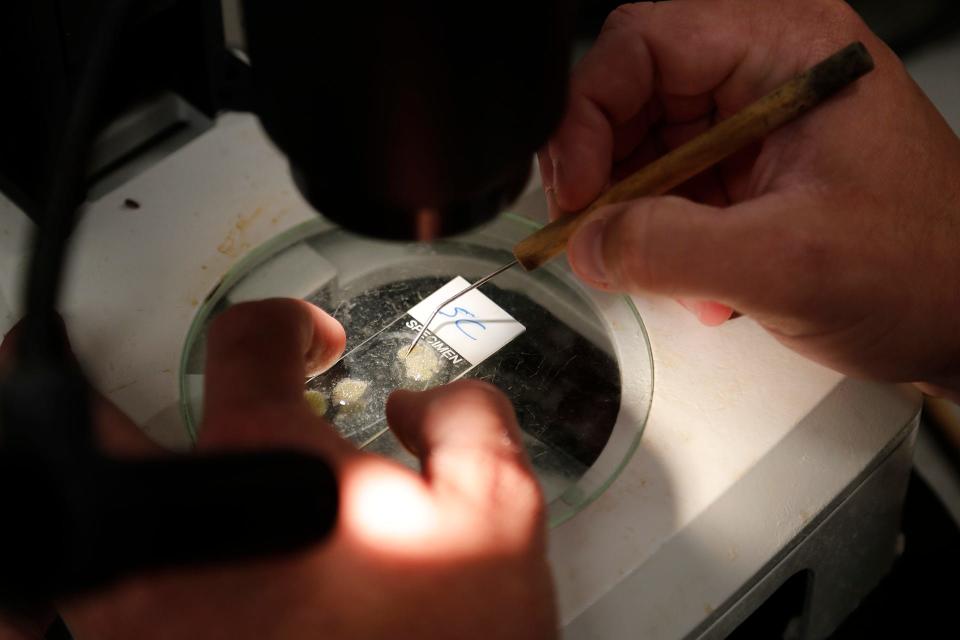

The DNR's fish hatchery is cool and moist, with cement temporary holding tanks in orderly rows throughout the building. Cordoned off from each other, different fishes paddle around while the DNR employees check the females to see if their eggs are ready.

"We have about a 30-minute window to get the eggs out of these fish," Cummins said. Egg development is divided into six stages. When the fish come off the truck, they are classified and receive a growth hormone that kick-starts the eggs' ability to fertilize. Employees have to keep a close watch, taking samples and monitoring the eggs' status to get the timing just right for fertilization.

Clad in waders, DNR employees scoop the fish out when it's time to fertilize. At this point in the season, Cummins said, the fish are ready to reproduce. The process doesn't require cutting any fish open. They are stunned with electricity, and for females, DNR employees strip the eggs from the female's vent, the place on its body that removes waste and extra water. For males, the employees palpate the fish's underside, doing the same as they do with the females so the fish excretes its semen from its vent.

Richmond Hill doesn't have the space to raise all the millions of fish they produce to stocking size, even with expansions in recent years to have 31 production ponds and three other ponds dedicated to kid's fishing events. The small fish are sent to other DNR hatcheries to grow to "fingerling" size, roughly an inch long. Other DNR hatcheries often send fish around once they reach that size, the hatchery sends them out to other DNR hatchery facilities to grow to "stage two," 6 to 8 inches long. From there, the DNR stocks them statewide.

Marisa is an environmental journalist. She can be reached at 912-328-4411 or at mmecke@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Savannah Morning News: Richmond Hill DNR fish hatchery spawns striped, white and hybrid bass