Battle over Medicare/Medicaid’s failure to cover approved Alzheimer’s drugs

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services is drawing fire for refusing to cover immunotherapy drugs that target early-stage Alzheimer’s disease, although the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved them.

At issue is a decision for aducanumab (sold as Aduhelm), which agency officials have said applies to all future treatments — including those not yet developed — that use monoclonal antibodies and received accelerated rather than traditional approval from the FDA.

That means the lack of general coverage applies to lecanemab (Leqembi) as well as other drugs in the monoclonal antibody treatment class targeting amyloid plaques in the brains of those with Alzheimer’s. The plaques are believed to be significantly involved in development and progression of Alzheimer’s disease.

The National Cancer Institute explains monoclonal antibodies as lab-created proteins that bind to specific targets — in this case, amyloid plaque. They are used against a variety of diseases.

The federal agency has deemed those drugs and future drugs in that class used against Alzheimer’s as “not reasonable and necessary,” which clears the way for the agency to refuse payment. But it’s a finding that confounds Alzheimer’s patients, their families and advocates, as well as many lawmakers and others, experts told the Deseret News.

The agency said it would cover the drugs for patients enrolled in approved federal studies, which advocates say are largely unavailable. “There are no opportunities to join these trials at this point. So it’s a closed door,” said Robert Egge, Alzheimer’s Association chief policy officer.

“We think what CMS has done by effectively denying coverage for this class of treatments is terrible for patients. And it can’t be justified in terms of the science we have today,” Egge said.

“Our basic call to CMS is just to be fair. Usually, a group asks for an exception. We are asking the opposite. Stop making an exception for us. Make the decision based on patients and the science,” he said, noting the decision amounts to saying “this whole class of drugs now and into the future, by presumption, is not reasonable and necessary.”

The backlash has included congressional committee hearings and protests. A bipartisan collection of 74 U.S. House members and 20 senators sent letters to Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra and CMS administrator Chiquita Brooks-LaSure asking that the agency reconsider denying coverage for lecanemab and other monoclonal antibodies. Brooks-LaSure has promised a decision in late June.

Members of Congress have also taken Becerra and Brooks-LaSure to task over the initial decision not to cover the drugs and for rejecting the Alzheimer’s Association’s request to reconsider.

During a hearing of the Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education and Related Agencies in March, Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, told Becerra that “CMS is blocking and acting as a roadblock for patient access to drugs that could be very helpful to them, particularly in the early stages of this devastating disease. I just don’t understand CMS’ misguided and outright unprecedented decision to not cover a whole class of Alzheimer’s drugs. It’s not CMS’ job to second-guess drug approvals. That’s not what CMS is supposed to do.”

Sen. Mike Crapo, R-Idaho, in a Senate Finance Committee budget hearing noted that the FDA’s “accelerated approval pathway has provided a lifeline for countless Americans years before these treatments could come to the market. This administration has taken unprecedented steps to erode this pathway.”

Meanwhile, the Veterans Administration has announced that it will provide the medication to qualified veterans who are 65 and older and in the early stages of the neurodegenerative disease. That raises the specter of a veteran being treated while a spouse in a similar stage of Alzheimer’s could be denied the treatment.

Baffling, heartbreaking disease

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services said more than 6 million older Americans have Alzheimer’s — a number expected to more than double by 2060 without treatments.

As the Deseret News has reported, researchers discovered two decades ago that immunotherapy could remove brain plaques in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s. That finding underpins the development of monoclonal antibody therapies including aducanumab, lecanemab and donanemab.

Alzheimer’s symptoms, though, come from tau tangles, Dr. Norman L. Foster, a neurologist and expert on Alzheimer’s clinical and imaging research, said earlier this year. He said amyloid accumulates outside the nerve cells and changes those cells’ environment so they develop neurofibrillary tangles that interfere with neuronal function.

Because plaque can be detected on positron emission tomography or PET scans a decade or more before Alzheimer’s symptoms appear, the holy grail of Alzheimer’s drug development would be preventing disease symptoms altogether.

While the monoclonal antibodies remove the plaque, experts say patients don’t get back function already lost, so using them early in the disease process is vital.

The FDA approvals of monoclonal antibody therapies specify their use at the early stage of symptoms. But patients have been put in limbo by the centers’ decision as their disease progresses, according to Alzheimer’s Association officials who note that more than 2,000 patients a day pass from that early symptomatic stage to moderate Alzheimer’s, for which no monoclonal antibody therapy is approved.

Critics also note that the decision marks the first time ever that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has said it won’t cover an FDA-approved drug for patients who qualify by diagnosis.

“It’s age discrimination and it’s disease discrimination,” said Jeremy Cunningham, public policy director for the Utah chapter of the Alzheimer’s Association.

The agency disagrees. A centers spokesman told the Deseret News by email, “Because of the early evidence and the immense burden of this devastating disease on the Medicare population, the Medicare (national coverage determination) provides coverage with evidence development to support rigorous studies to help answer whether this drug improves health outcomes for patients.”

He noted that “the (determination) includes a coverage pathway for broader access to these drugs if they receive FDA traditional approval. CMS is committed to being nimble when reconsidering this coverage framework in light of any new evidence related to the clinical benefit of this drug, and we continue to encourage clinicians, patients and caregivers to send us relevant evidence.”

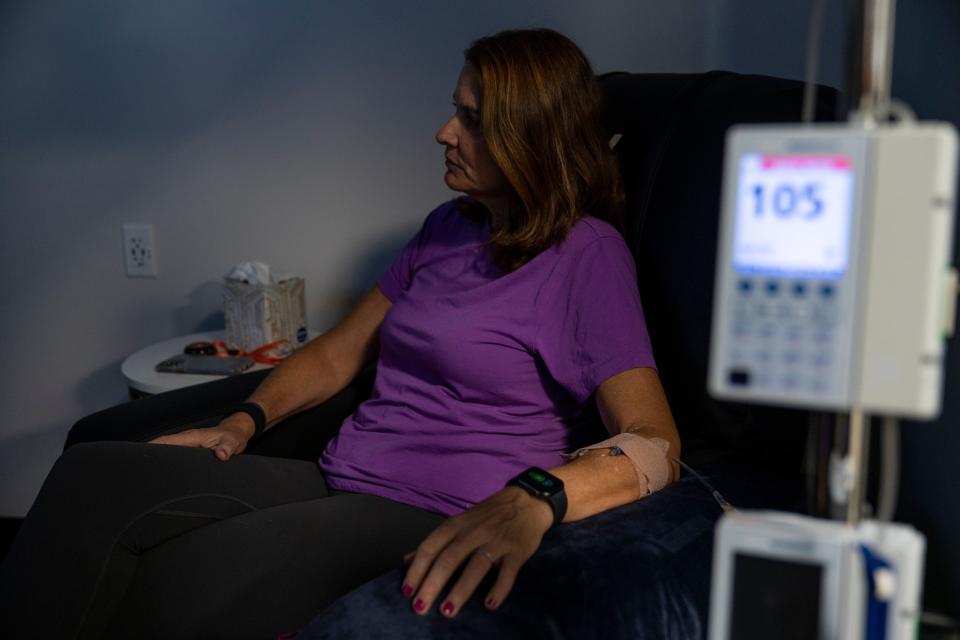

But unless Medicare begins to cover the drugs or patients can find a relevant clinical trial, those with early-stage Alzheimer’s will have to forego treatment or pay out of pocket, as the Tampa Bay Times reported Florida resident Michelle Hall and her husband Doug have been doing. She was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in her mid-50s. They decided to pay for infusions of aducanumab, which the Halls hope will slow the progression of her Alzheimer’s.

Cunningham is among those who say most people with the diagnosis cannot afford to bear the entire cost themselves.

Related

In April, Brooke-LaSure told a congressional hearing that Medicare will cover Leqembi for all patients the FDA finds eligible if the drug receives full approval in July. But as CNBC reported, “the Alzheimer’s Association says access to the drug will remain restricted due to a requirement that patients participate in registries that collect data.”

The association, as well as others, want the agency to drop any registry requirement and treat the drug like any other that’s been approved. Countered Brooks-LaSure, “All that we are indicating is that individuals who are taking the drug, their doctors will put that information in a privately owned registry,” per CNBC. But no registries have been set up and Egge said it’s not the job of “private entities” to do so. Further, access could be restricted for those in rural areas, among others.

Egge and others have also questioned how easy the registries — if created — will be to navigate.

Reason to hope

The monoclonal antibodies treatment class also includes Eli Lilly’s donanemab. Donanemab did not receive accelerated approval because the FDA required a certain number of patients to be in the trial for 12 months. In a clinical trial, the company said the drug had cleared amyloid plaque for many of the patients enrolled before the year mark so the treatment was stopped. The company is now pressing for traditional approval.

Egge said that the recent results of monoclonal antibody trials have been clear and very hopeful.

For instance, Eli Lilly said donanemab showed a 35% to 40% effective rate and nearly half of those participating in the phase 3 trial showed no progression of the disease at the one-year mark. More than half cleared all amyloid plaque at that point, as well, while nearly three-fourths no longer had amyloid plaques within 18 months.

The Alzheimer’s Association considers the immunotherapies a breakthrough that marks the beginning of an era of improvements. While the slowing of the disease progression has only been moderate, drug development is not usually an immediate home run, Egge said. Treatments and cures come in stages, as they have with everything from polio to HIV/AIDS.

The association is calling on people to let their members of Congress know they are upset about the centers’ decision to deny coverage for treatment outside a research study.

And more protests are in the works, including one by the Alzheimer’s Association’s Utah chapter at the state Capitol at 10 a.m. June 21.

No slam dunk

While some suggest Medicare and Medicaid officials want to get out of paying for monoclonal antibodies treatment, which is expensive, others say that’s not the issue and can’t legally be a factor in the centers’ determination.

The Deseret News reported in January that “the class of drugs is not so unique that the agency doesn’t know what to do — or so expensive that it won’t. Immunotherapy for multiple sclerosis is covered though it costs more than $50,000 a year.” Lecanemab’s cost is similar to aducanumab at around $26,000 a year.

Per Cunningham, the $26,000 price tag is a fraction of what Alzheimer’s and related dementias cost — estimated at an average of $41,000 a year for a family that includes someone with Alzheimer’s.

A more likely issue is controversy surrounding aducanumab’s approval. A congressional investigation found “irregularities” in the 2021 approval process. The report said the FDA worked too closely with the pharmaceutical company in putting together the application. Additionally, an FDA advisory committee had recommended against approval. Some have called aducanumab’s power against the disease underwhelming.

Even in the best case, the drugs are not a cure. The reduction in cognitive decline has been modest, some experts told The Wall Street Journal, which also noted some potential side effects. About 1 in 8 of those in the clinical trial of lecanemab, made by Biogen and Eisai, developed swelling and bleeding in the brain.

Monoclonal antibodies are not the only treatments being studied for Alzheimer’s. As the Journal reported, “some researchers are looking into whether traffic jams within endosomes, a type of specialized structure inside cells, or dysfunctional activity of cells called microglia could contribute to Alzheimer’s, among other possible risk pathways.”