Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis: what’s fact and what’s fiction?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Playing Elvis Presley in the new Baz Luhrmann-directed biopic, there’s no faulting Austin Butler’s precision-perfect stage performances. See him belting out Suspicious Minds in Las Vegas – every hip-swing, every lip curl, each flurry of moves is perfectly observed and recreated. Elvis lives.

But how real is Luhrmann’s biopic overall? Looking at the trailer alone, Elvis historian Billy Stallings said the film is “not for us Elvis purists” and it will likely “make you mad”.

The film tells the story of Elvis’s life and career – told through the prism of his tricky relationship with devious, divisive manager, Colonel Tom Parker (Tom Hanks). Is it true to life? Or are the facts all shook up? Here’s what Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis gets right and wrong about the King of Rock ‘n’ Roll.

How big was Elvis’s debt to black culture?

As a child in Tupelo, Mississippi, Elvis runs around with a Shazam-style lightning bolt around his neck (unlike the jumpsuits, it’s a fictional adornment – though young Elvis really was a lightning bolt-emblazoned Captain Marvel Jr).

After peering into a down-and-dirty juke joint — where blues legend Arthur Crudup sings That’s All Right – Elvis attends a gospel revival tent.

Elvis really did grow up within the black community and saw Crudup play in juke joints. The revival scene – a Luhrmann-esque moment in which Elvis fuses the concept of blues and gospel and sexuality, like a spiritual awakening – is also based on fact.

According to childhood friend Steve Bell, Elvis would lose himself among the revellers. A preacher once told Bell to “leave [Elvis] be. He’s with the Spirit”.

The film reiterates Elvis’s deep connection to black culture (Elvis expressed some white guilt, commenting on how That’s All Right, his debut single, didn’t get the credit it deserved until he “goosed it up”).

But Elvis’s other major musical influence – country – is largely ignored, portrayed as profoundly uncool next to rhythm ‘n’ blues.

Did Elvis’s manager schmooze him on a fairground ride?

Hanks’s Colonel Parker first sees Elvis perform at the Louisiana Hayride in 1955 – the real-life musical showcase on which Elvis initially made his name.

Colonel Parker biographer Alanna Nash noted that Parker's real introduction to Elvis is a mystery, though it’s true that – as seen in the film – he began appearing at Elvis’s gigs, lingering in the shadows. Elvis in the film even wears a historically accurate pink-and-black suit (less accurate, according to Billy Stallings, is the shade of Elvis’s pink Cadillac – not Elvis Rose pink).

Luhrmann invents a typically lurid scene, in which Parker schmoozes Elvis at the fairground – atop a Ferris wheel and in a hall of mirrors – a nod to Parker’s carnival worker roots (though he'd given up the carny life by then).

The real pivotal meeting between Parker and Elvis happened at a café in Memphis, where Elvis and his guitarist, Scotty Moore, met the Colonel properly for the first time. Elvis’s group had received a standard rejection letter from Parker’s booking agency just three weeks earlier.

Was Elvis as modest as he claimed?

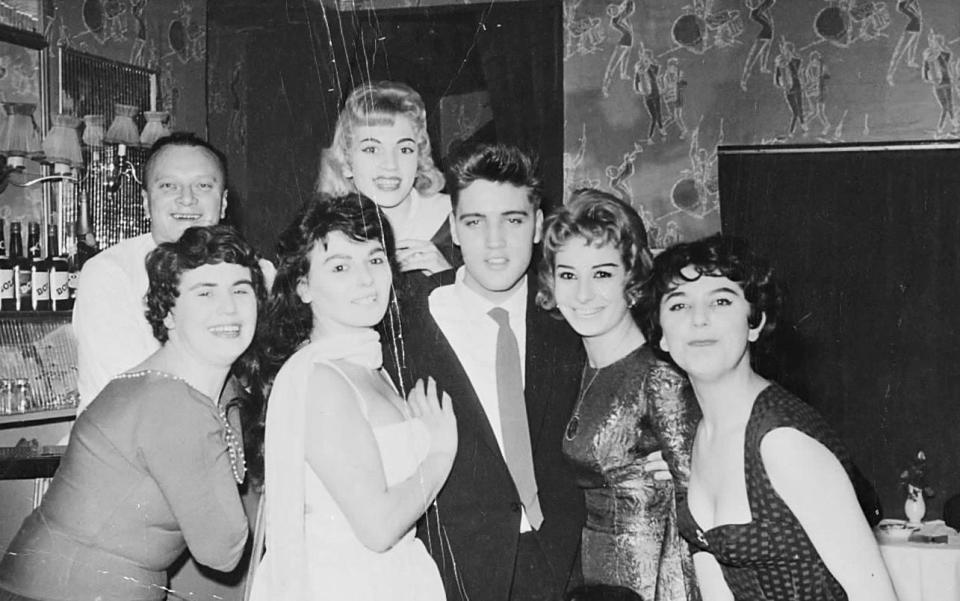

As seen in the film, Colonel Parker didn’t watch the soon-to-be King; he watched the audience – in this case, the primal, convulsive reactions of women. It’s little wonder that the film gets this detail right: Elvis’s neat supernatural power over girls. Elvis was packing out dive bars with excitable girls way before Parker showed up.

“In towns where he’d had radio exposure, it was a very frenzied type of reaction,” said Elvis’s former manager, Bob Neal. “The girls were screaming, jumping up and down and passing out.”

In May 1955, at a concert with 14,000 fans in Jacksonville, Florida, Elvis joked that he would see the girls backstage, causing a riot. A stampede of sex-hungry fans chased Elvis into the locker room, forcing Elvis to scarper on top of the showers as they literally tore his clothes off.

Also correct is that Elvis didn’t know what the excitement was about at first. In the film, the band tells him, “It’s the wiggle!” Elvis once said: “The first time that I appeared on stage... I really didn't know what all the yelling was about. I didn't realise that my body was moving. It's a natural thing to me.”

How evil was Elvis’s manager ‘The Colonel’?

That’s ultimately the hook of the film, which questions whether Parker drove Presley into an early grave. “I did not kill Elvis,” he says. “I made Elvis!”

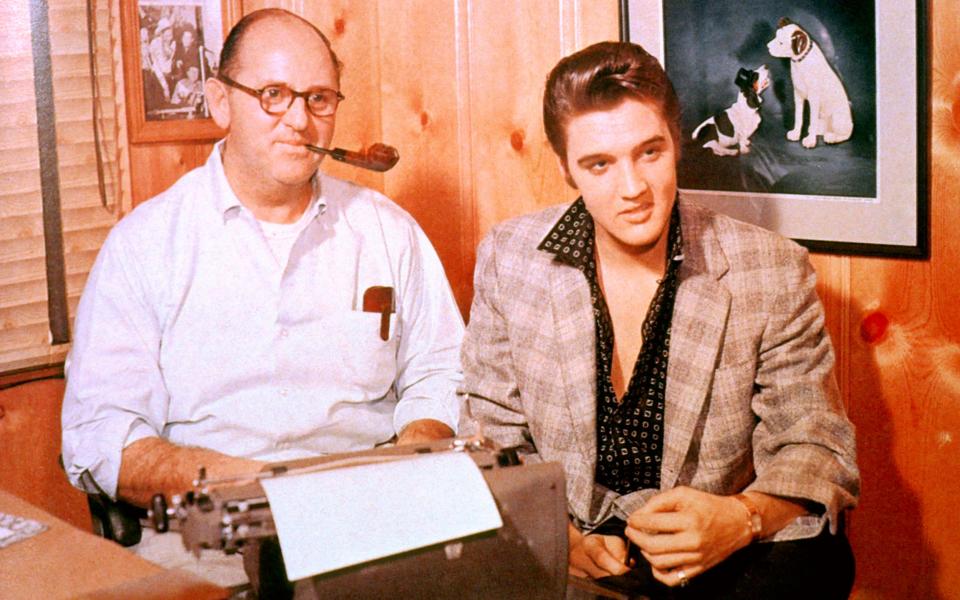

The Colonel is played as a panto villain. Hanks – beneath grotesque prosthetics – talks with a pronounced, cartoonish Euro-accent, much stronger than Parker in real life.

As seen in the film, Parker was a merchandising genius – he even sold “I hate Elvis” badges to monetise Elvis’s detractors. “At a time when most managers did little more for their artists than book concert dates, Parker perpetually figured out new ways to exploit his star,” wrote Alanna Nash.

It’s also correct that he exerted huge control over Presley’s film contracts, TV appearances, and personal life.

The film claims that Parker took 50 per cent of Elvis’s earnings. Parker’s original deal was for 25 per cent commission, but he found increasingly creative ways to take a bigger cut – up to 50 per cent or even more.

Four years after Presley’s death, a judge ruled that Parker’s compensation was “excessive” and ordered Presley’s estate to sue him for alleged fraudulent business practices.

How criminal was Elvis’s wiggle?

Both on screen and in real life, Elvis’s hip-swivelling sexuality caused controversy – a moral panic over his pelvis’s potential to corrupt America.

In one sequence, Elvis plays a concert in Memphis and is warned by officials to not wiggle his hips. Police surround the stage but the rebellious Elvis can’t help defying authority: he wiggles those hips regardless and causes a near-riot, almost getting himself arrested.

The film actually conflates two real-life concerts from 1956: one in Memphis on July 4 and another in Jacksonville on August 10.

There was indeed a big police presence in Memphis – police, firemen, and shore patrol, in fact – but they were keeping fans in order, not arresting Elvis for being too sexy. Elvis did leave in a squad car though, for his own safety. Elvis had riled up the fans so masterfully that it was, according to biographer Peter Guralnick, “a moment of unmitigated triumph”.

It’s true, however, that in Jacksonville (where he’d previously caused a riot) a judge effectively banned him from wiggling his hips. The real Elvis was more restrained than Luhrmann’s version. Rather than wiggling his way into legal trouble, Elvis mocked the judge (who was in attendance) by wiggling just his little finger, which still sent the girls wild.

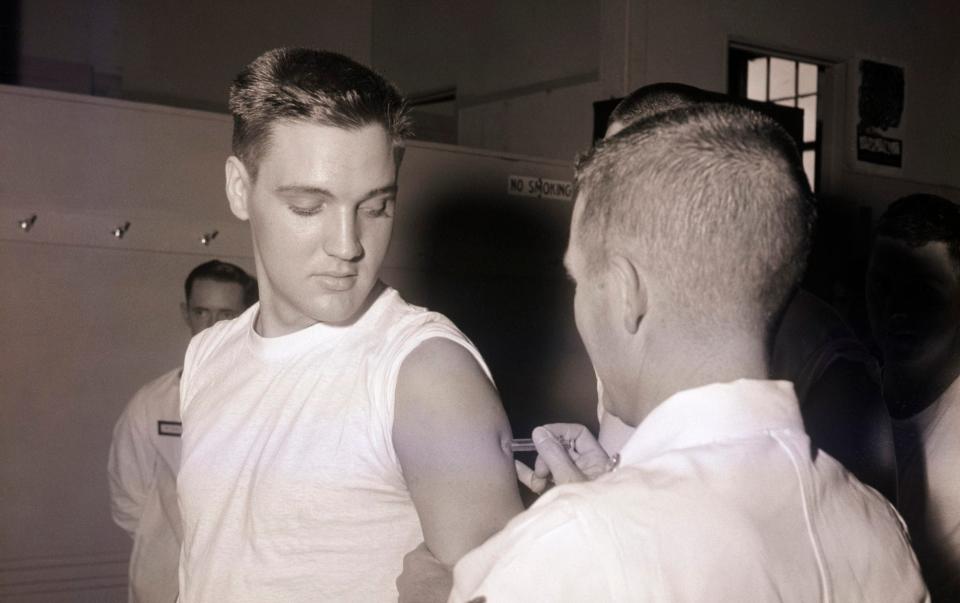

Was Elvis drafted into the military?

In the film, Colonel Parker sends Elvis to serve in the army, stationed in Germany, as a penance for Elvis’s scandalous, riot-fuelling hip-swivelry.

In truth, Elvis was drafted. Peter Guralnick’s Elvis biography, Last Train to Memphis, describes how the armed forces were pitching suggestions for how Elvis could be used, including a special “Elvis Presley Company”.

But the Colonel persuaded Elvis to serve like a regular joe – for the sake of good PR.

According to Alanna Nash, the Colonel was actually scheming in the background. It was inevitable that Elvis would be drafted, so the Colonel wrote to the Pentagon, requesting Elvis be put in the Special Services entertainment division. But Parker didn’t really want Elvis singing and dancing for the troops – the Colonel would make zero commission.

At the same time, Parker leaked a story to Billboard magazine saying that Elvis would join Special Services – which was news to Elvis when he opened the magazine.

It was all a ruse: to get Elvis to cut a deal with the draft board and serve as a regular soldier. “When he got out two years later,” wrote Nash. “He would be visibly tamed, transformed into a pure symbol of America, a clean-cut god for the masses. No more would he personify the music of a subversive and dangerous subculture, led by wild deejays high on pills and payola.”

Was the Colonel a murderer?

Luhrmann’s film correctly shows how Elvis wanted to play concerts overseas, but Parker always prevented him. The suggestion is that because Parker was not really a Colonel, but an illegal alien from the Netherlands, he can’t leave the country.

The film doesn’t flesh out a more sinister story: that Parker – real name Andreas Cornelis van Kuijk – had allegedly murdered a woman in his hometown of Breda and fled to the US.

The story came from an anonymous tip off to a Dutch journalist, and there was indeed an unsolved murder in Breda the month van Kuijk left for the States.

Todd Slaughter, a friend of Parker’s in later life and president of the UK fan club, doubted that Parker was capable of it. “I really don’t think there was a murder in him,” Slaughter said. “He was a noisy character, but I don’t think there was any brute force within his psyche at all.”

Did Elvis really want to be the next James Dean?

One fantastical element surrounds the 1968 “Comeback Special” that marked Elvis’s return to live performing. It began as a Christmas special, though TV producers talked Parker out of the Christmas theme.

In the film, however, Parker is adamant that the show be Christmas-themed so he can sell Elvis-branded gifts and baubles, forcing Elvis and the producers trick the Christmas jumper-wearing Colonel into thinking the festive theme will go ahead.

One invented scene sees Elvis and the TV producers meet by the Hollywood Sign, where – in a symbolic moment – they conspire to make Elvis culturally relevant again. Elvis says he wants to be like James Dean, which was true – he wanted to be taken seriously as an actor and would quote entire scenes from Rebel Without a Cause.

It’s also true that Elvis saw reports of Robert Kennedy’s assassination during the production of the ’68 special. What’s played down is the fact it sent Elvis into a bit of a spin. Following the JFK assassination, Elvis had become a conspiracy nut – ironic considering the later conspiracies about Elvis faking his own death.

Did Colonel Tom Parker really hoodwink Elvis into paying his debts?

Luhrmann labours the link between the Suspicious Minds lyrics and Elvis’s life situation (about as subtle as a gyrating pelvis to the face). Elvis is not only grounded in the United States but stuck in a Las Vegas residency – where he plunges, as in real life, into a sweaty, paranoid mess.

According to the film, Parker trapped Elvis in Vegas’s International Hotel as a means of paying off his own gambling debts – a clandestine deal that Parker writes down on a napkin.

It’s true that following Elvis’s first performance – an explosive, triumphant night in Elvis history – that Parker sat with Alex Shoofey, president of the International, and scribbled the terms of a handshake deal on a table cloth: $1 million for eight weeks per year, for five years, plus a holiday in Hawaii for the King.

Shoofey later said that Parker could have asked for more, or a sliding scale, but didn’t. Why? Alanna Nash suggested that it could have been for Parker’s own gain: all the lavish perks he enjoyed from their long stays at the casino, or the bosses “forgiving at least a portion of his mounting casino losses”. Parker’s gambling habit, wrote Nash, had become a “ferocious beast”.

Alex Shoofey described how the Colonel’s gambling was good for “a million dollars a year”. Others said more – up to $100,000 per night – meaning that every dollar that the casino paid for Elvis, the Colonel put back on the tables.

Who was the real ‘Dr Nick’?

Also lingering in the shadows is Dr Nick, who is summoned to administer some dodgily-prescribed pick-me-ups. At one point he sticks a collapsed Elvis with a needle so the King can leap back up and perform.

The real Dr Nick was George C. Nichopoulos, who worked as Elvis’s doctor for 10 years – until Presley’s death in 1977 – providing all kinds of uppers, downers, laxatives, and shots. Beginning as Elvis’s doctor in Memphis, he went on tour and attended shows in Vegas. Elvis once accidentally shot him in the chest (barely a scrape) while fooling around with a gun.

Dr Nick was later demonised by some fans – even receiving death threats – but he managed Elvis’s out-of-control drug addictions and supply. He even gave Elvis specially-manufactured placebos. And when Dr Nick wasn’t on hand, Elvis had no problem finding shady doctors who would happily dish out drugs.

Still, between 1975 and 1977, Dr Nick prescribed Elvis 19,000 doses. After Elvis’s death, a tribunal board found him guilty of overprescribing and suspended him temporarily. In 1980, he was charged with abusing his licence but acquitted. He was eventually stripped of his licence in 1993.

And what about Elvis’s dark side?

The film is also notable for what it leaves out. Elvis’s wife, Priscilla (Olivia DeJonge), is just a fleeting presence, while the story skirts around the troubling fact that Priscilla was just 14 when she first met Elvis, who was 10 years her senior.

Indeed, Luhrmann’s film has little of the filth beneath the spangly jumpsuits: no stories of other teenage girls; no reports of forceful, voyeuristic sex; no junk food binging or fat Elvis; no meeting President Nixon and slating The Beatles; no incontinent Elvis in adult nappies; no overdose-induced comas; and certainly not the full extent of his health and drug problems.

Perhaps that’s all being saved for Luhrmann’s four-hour cut.

It’s no surprise that the film tells the glossy version of the Elvis legend. The Elvis estate gave Luhrmann permission and the film has been praised by Priscilla and their daughter, Lisa Marie.

There is a thematic truth, though. As Colonel Parker says, “Without me, there would be no Elvis Presley.”

Elvis is in cinemas now