Beacon Journal correspondent’s 1945 articles paint vivid portrait of World War II

James S. Jackson didn’t see the worst of battle in World War II. He wasn’t at the front line. He didn’t see anyone get killed.

But he saw enough to decide that there shouldn’t be any more wars.

'I did not touch a gun': World War II veteran, 100, was a conscientious objector honored for valor

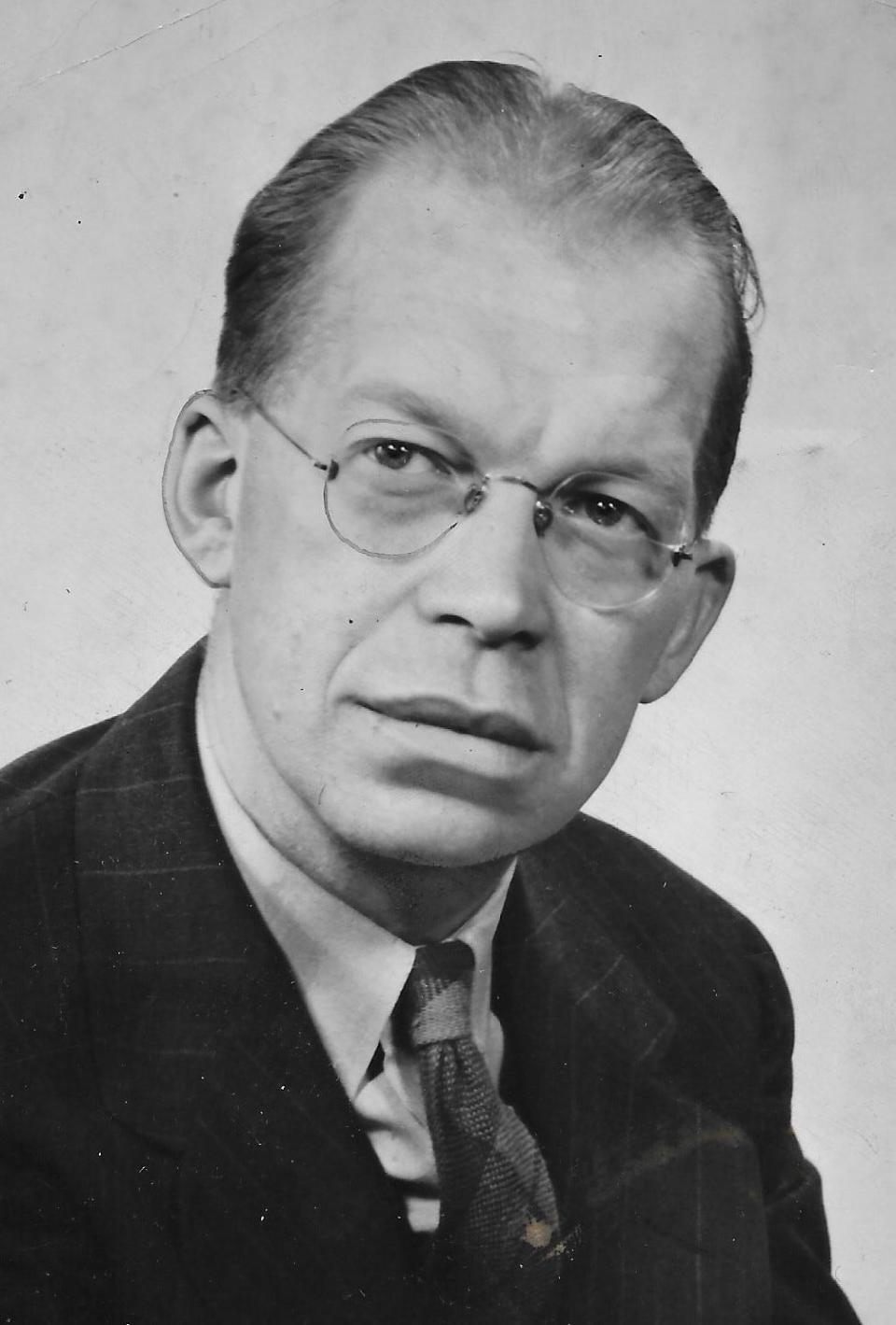

Jackson (1905-1985), associate editor of the Akron Beacon Journal, served as a war correspondent for Knight Newspapers during the spring of 1945 when the conflict was winding down in Europe. His five-week assignment was to report on the use of war products manufactured in Akron, Chicago and Detroit, home to three newspapers in the chain, but the focus widened along the way.

Jackson, who was 40 at the time, was known for writing the “Behind the Front Page” column while his wife, Margot, an Akron librarian, wrote book reviews and later a history column for the Beacon Journal. The couple had three children: John, Mimi and Susan.

Daughter Mimi Jackson Lewellen of Wooster has transcribed nearly 50 of her father’s articles from March-April 1945 into a bound volume. The stories provide a fascinating glimpse of the war through the eyes of a civilian.

Lt. Gen. Brehon B. Somervell, commander of the Army Service Forces, invited Jackson to the war zone. Before the trip, the journalist had to fill out a security questionnaire, take vaccines for typhoid, typhus, smallpox and tetanus, and attend briefings at the Pentagon in Washington, D.C.

War correspondents were required to submit their articles to military censors for clearance. They had to be vague about locations so enemies could not pinpoint the position of Allied forces. Some stories were delayed for weeks as a precaution. The copy was dispatched to Akron via airmail, bomber pouch or other means.

Jackson’s columns started out lighthearted and became increasingly sober.

In a March 16 article datelined “OVER THE ATLANTIC,” he described flying 180 mph at 9,000 feet in a four-motored C-54 plane. He flew from Washington to Newfoundland to the Azores of Portugal.

“I slept just intermittently, possibly because I was anxious to be awake for sunup,” Jackson wrote. “I did wake up in time and it was worth it to see the brightening glow above the solid mass of cotton batting that was below. Finally, the sun burst out in all its yellow glory, far ahead and just a little to the left of us. Soon the clouds began breaking, and occasionally one could glimpse the whitecaps on the sea.”

Following an hour layover in the Azores, the plane flew nonstop to Paris. The entire trip took 28 hours, which Jackson considered remarkably speedy. When he traveled by ship from New York to Glasgow in 1938, it took 11 days.

When Jackson met with U.S. military personnel in Paris, an officer inquired about the flight to Europe.

“Just to think that at the speed you came over, my home is only 36 hours away,” the captain said. “And yet I haven’t been there for two and a half years and I don’t know how much longer it’ll be.”

Fashions in France

One of the first things Jackson noticed in Paris was the clothing.

“Many of the women are dressed with a certain stylishness, yet their clothes never look new,” he noted. “The women’s hats are something out of this world — there seems to be a contest on to see who can erect the highest mountain of fabric. Hair-dos are much the same — straight up from the forehead.”

A strange noise drew his attention to the pavement.

“Apparently, the soles of most women’s and children’s shoes have been made of wood for the last few years,” Jackson wrote. “The sidewalks resound to a constant clack-clack of footsteps.”

The Allies had liberated Paris from German occupation in 1944. The journalist asked a French woman how life had been under German occupation. There was little food, sparse electricity and no heat.

“We just lived,” she said.

When he gave her a tiny bar of soap from his hotel, the woman took a deep whiff.

“C’est merveilleux,” she said.

Jackson rode 120 miles by Jeep over rough roads to Reims in northeast France.

“At first, you feel as though you might fall out all the time,” he wrote. “And you notice all the rattles and jounces. But, in time, you sort of get in rhythm with it, much as a horseback rider must do.”

He saw overturned trucks and burned tanks. Some roads were pounded to pieces.

Jackson rode with Pfc. Jerry O’Wiley, a combat engineer from Texas who had been transferred to courier duty. People today would recognize his condition as post-traumatic stress disorder.

“They said I was suffering from battle fatigue, whatever that is, so they detached me from my outfit and put me on this job," O’Wiley explained. “I was a little jumpy, but I’m getting over it.”

Just then, three planes zoomed overhead.

“If that had happened two months ago, I’d have jumped in the ditch quick,” he said.

Another city in ruins

In the Belgian city of Bastogne, Jackson observed the devastation left behind by the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944.

“After you’ve seen dozens of towns and villages in ruins, Bastogne doesn’t look much different from the others — roofs wide open, houses sliced in half, shell holes through some walls and the mark of machine-gun bullets on others, rubble everywhere and once in a while a citizen pitifully trying to set up housekeeping again,” Jackson wrote.

On Easter Sunday, Jackson had a private meeting with Gen. George S. Patton at his headquarters. Patton coaxed his white bull terrier, Billy, off a leather chair and invited Jackson to sit.

As was customary, the reporter wasn’t permitted to quote the general, but he was allowed to write his impressions of the man.

“He stands erect,” Jackson wrote. “On the left breast of his battlejacket are four long rows of ribbons, proudly worn. His white hair is short and thin. His blue eyes are keen and clear. You wouldn’t think of calling him ‘Georgie’ to his face. But that’s what his men call him.

“The general is keenly decisive. There are no ifs, ands, or buts.”

The fighting had subsided by the time Jackson rode in a caravan toward the Rhine River. It took 90 minutes to travel 2 miles. Bulldozers had cleared a path just enough for vehicles to pass, but debris blocked side streets.

“We wondered how many bodies were beneath the ruins,” he wrote.

Crossing into Germany

Army engineers had built a 1,896-foot steel bridge on dozens of inflated pontoons that had probably been made in Akron. Jackson crossed the river into Germany.

He interviewed former prisoner of war Michael Celuzza, 19, a soldier from Fitchburg, Massachusetts, who had been released days earlier. In five months of captivity, the soldier’s weight fell from 165 to 120 pounds.

“We were always hungry,” Celuzza said. “We had one loaf of bread a day for each six men. Thirty-five of us shared a 2-pound can of meat a day. That was all we had except for what we could scrounge.”

When U.S. forces drew close, German guards hid the prisoners in a tunnel with nearly nothing to eat, he explained. Finally, the guards gave up and set the captives loose.

Jackson witnessed when Celuzza reunited with his brother Vincent, 26, a surgical technician. The two men hugged each other and jumped for joy at a field hospital.

The rolling hills of Germany reminded Jackson of Pennsylvania — except for the craters from artillery shells and muddy ruts from tanks.

“In a little town where I stopped for mess, a dead German soldier lay on a sidewalk,” Jackson reported. “He had been shot, I was told, as he tried to sneak out of a cellar where he was hiding. The sight of his body was strange enough to a newcomer to the battle area, but even more strange was the fact that civilians and soldiers were passing by constantly and paying no attention to it!”

Most German soldiers in the region had given up with little resistance, he noted. A few hid in the woods and fired shots when U.S. vehicles passed. It was only a matter of time before they surrendered, too.

At a roundup point, Jackson said he got a good look at Adolf Hitler’s “master race.”

“They were a motley lot — young and old, erect and stooped, mostly small and wearing a dozen different types of uniforms,” he wrote.

They were hungry and cold after hiding in the hills. One soldier was a 16-year-old boy who had been in the service for three weeks.

Sprawled on the ground was a dead Nazi covered in a coat.

“He is not a pretty sight,” a sergeant told Jackson. “He sneaked into this town last night and tried to get some food. He failed to stop when one of our men challenged him and he got shot through the head.”

The debris of war

For 24 hours, Jackson rode across Germany with a three-man crew on an M19 motor carriage pulling a 10-ton trailer loaded with 24 tons of large caliber shells for the front line. They had covered only 125 miles in one day.

“Through the narrow streets of demolished villages we pushed our way as sullen citizens glared at our death dealing cargo,” Jackson wrote. “In almost every mile of countryside there was the debris of war, burned-out tanks, upside-down trucks, dead horses, smashed pillboxes, slit trenches, empty wire spools, helmets, gas masks, shell casings, gun mounts and one dead German.”

Heading the other way were trucks filled with prisoners, liberated laborers and refugees. They waved to the Americans.

Jackson watched in a town square as Germans read a newly posted proclamation.

“To the people of Germany,” U.S. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower wrote. “The Allied Forces serving under my command have now entered Germany. We come as conquerors, but not as oppressors.”

Jackson visited two field hospitals in tents. Patients, many who had been liberated from German labor camps, arrived by ambulance and left by airplane.

“In a world that is all men — mostly dirty — it is something of a shock to see the trim and pretty girls who are nurses in these hospitals,” Jackson wrote.

He interviewed Capt. Eva Mazur, chief nurse from Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, about the working conditions.

“The first couple of nights, we didn’t get much sleep because those big guns would keep going off and throwing shells right over our heads,” she said.

Conditions were rough at the hospital, but she wasn’t complaining. She couldn’t imagine serving anywhere else.

“I’d be afraid I was missing everything in life if I weren’t up here,” Mazur said.

At another hospital, Jackson visited the bedside of a soldier who had been shot in the chest by a sniper.

“When do I get out of here?” the soldier asked.

“Better stick around a while,” Maj. Stanley O. Wilkins replied.

Outside the tent, the major told the reporter: “That boy’s hurt worse than he thinks. But his spirit, like that of so many others, is wonderful. He insists that he’s got to get back to his regiment.”

Return trip to Ohio

Jackson’s assignment ended about a month before May 8, 1945, V-E Day, the date that Germany officially surrendered.

Returning to Paris, he began to prepare for the trip home. He shared a ride from the airfield with a fellow American.

“Where are you from?” he asked.

“Akron, Ohio,” Capt. Alvis E. Isner replied.

The two agreed to meet for lunch the next day at a Paris hotel. On the way to meet Jackson, Isner bumped into Lt. William P. Bebout, a Lambda Chi fraternity brother from the University of Akron.

Three Akronites in one place? What were the chances?

The return flight to the United States took more than 30 hours.

Jackson’s war stories continued to be published after he was back in Ohio. Some of the delayed articles finally received clearance from censors.

In one of his last war columns, he described what he had witnessed during five weeks in France, Belgium, Luxembourg and Germany.

Wars cost too much, he declared. The oil, steel, coal, wood, chemicals and labor could have gone to make people live more comfortably instead of being used to kill and maim them.

He lamented the “broken bodies and twisted minds” that would keep some people from ever living normal lives again. He noted the heartbreak of separation and the mental anguish of uncertainty.

And the greatest cost of all was the terrible loss of life “for so many million men, women and children who had no personal quarrel with anyone — who asked only to live in peace but were ruthlessly deprived of their very right to exist.”

Jackson had a brief glimpse of war, but he had seen enough.

“This is only part of the story,” he concluded. “The men who have been overseas for lengthening years, the men who have been wounded, the parents, wives and children who have waited at home; those whose sons and husbands won’t come back — all those know better than I why there mustn’t be another war.

“I had just a small taste on a spoon.

“But now the words mean more than they did before:

“THERE MUST NOT BE ANOTHER WAR!”

Mark J. Price can be reached at mprice@thebeaconjournal.com.

Paying tribute: Memorial Day 2022 events planned throughout Greater Akron

Local history: Hollywood star David McLean, who played Marlboro Man, was an hombre from Akron

This article originally appeared on Akron Beacon Journal: Beacon Journal correspondent’s 1945 articles offer glimpse of WWII