‘Beatdown’ by Tulare County Sheriff’s ‘goon squad’ alleged in federal civil rights case

Ramiro Huerta admits he was irate and then some when he repeatedly called law enforcement to complain about squad cars shining searchlights through the windows of his family’s Strathmore home.

All he wanted, he says, was for the lights to go away. What he got instead was the entire uniformed night shift at the Porterville substation of the Tulare County Sheriff’s Office – four deputies and their sergeant – showing up at his home hours later and proceeding to wrestle with him and to hit, kick, and swat him with batons before he was hogtied and carted away in a patrol car.

The results included serious injuries for Huerta followed by resisting arrest and other charges. A jury cleared him of any wrongdoing except making annoying phone calls.

Also resulting from the violent confrontation of April 25, 2017, is a federal civil rights lawsuit against the Sheriff’s Office, an already expensive suit that could go to trial in Fresno this summer or fall.

With considerable evidence on his side, Huerta contends he was beaten by a gang of deputies who wanted to teach him a lesson. Among the evidence, none of the five men was wearing a functional body camera during much of the action.

Huerta, 47, is an openly gay Latino and he believes that may explain why he was assaulted. He is also an unemployed florist who moved to Strathmore to help care for his aged parents. He takes prescription medication for his nerves but they weren’t helping much that evening. He says he reacted at full throttle because he felt like he was under siege.

Officially the visit to his home was a welfare check but it turned into what one former sheriff’s official and one of his lawyers called a “beatdown.”

What happened at Strathmore home the night of April 25, 2017

The lights started flashing around 7:30 p.m. while Huerta and his mother were watching a “Golden Girls” rerun on TV. First Huerta tried calling the Porterville Police Department to complain. Dispatchers there told him they don’t patrol Strathmore. They correctly directed him to the sherifff’s Porterville substation.

So Huerta started calling there, and he kept calling. Over and over. But the lights kept shining up and down his street. He wasn’t getting any satisfaction and was cursing anyone who picked up the phone.

Deputies arrived after 10 p.m., hours after the calls had ended. Huerta and his parents were in bed. The men in brown uniforms banged on the metal security door. Heated dialog quickly ensued, leading to Round 1.

Briefly a couple of body cameras recorded the action as deputies grabbed Huerta. He fell to the floor inside the house and the deputies went with him. He swung and kicked and so did they. Huerta was slugged in the face at least twice. Somehow he squirmed free.

“I managed to make it to the steps,” he recalled during an interview at his home. “I fell to the floor, my mom was standing somewhere, right there. They pushed her onto the couch and shoved the couch to the wall and made more space where they could kick me, baton me some more.”

Huerta managed to get the deputies to leave the house. He closed the door behind them. But they weren’t done.

At the direction of their sergeant, now lieutenant, Ron Smith, they didn’t drive away. Instead they hid in the bushes that surround the house. There, quietly, in the dark, they waited in hopes he would come outside to lock the front yard gate. When he did, they jumped him for Round 2.

The plan, the deputies said in reports and court testimony, was to get Huerta outside so he could be arrested for being drunk in public even though there was no obvious evidence that he was. And when he was lured outside, he went no farther than his front lawn. Few people have been successfully prosecuted for public drunkenness on their own property. His blood was never drawn to be tested for alcohol.

A couple of the deputies were wearing functional body cameras when they arrived. The first round was videotaped. But by the time things got rougher outside, none of them had a working camera, either by design or coincidence. That’s a violation – five violations, actually – of department policy and an issue that will likely loom large in federal court.

Huerta was only wearing a yellow tank top and briefs when deputies handcuffed him, hogtied his bare feet to his arms and carried him to a squad car. They pepper sprayed him because he was kicking and refusing to get into the vehicle. Huerta says he couldn’t get in because of how his hands and feet were shackled together.

His lawyers say Huerta still hasn’t fully healed from the eye damage and is being treated for traumatic brain injury. They say the blows broke one of the bones that protect his eyes.

The county lawyers have disputed that he sustained brain injury.

Huerta convicted only of making annoying calls

The Sheriff’s Office and the deputies tell a different story than Huerta’s, of course, but not as different as might be expected. Testimony from the deputies puts the blame on Huerta but also raises questions about the deputies’ training and motivations.

Their first chance to tell their side came when the county took Huerta to court. Six months after the confrontation, his lawyers filed the federal excessive force/civil rights case. Three weeks later, Tulare County prosecutors charged Huerta with resisting arrest, assaulting officers and making annoying calls. Huerta and his lawyers contend the charges were filed only as a bargaining tool to make the federal lawsuit go away. The county lawyers say they don’t operate like that.

The result was a 15-day trial in Porterville Judge Walter Gorelick’s courtroom. Huerta was convicted only of making annoying calls, a type of charge more likely to lead to a citation rather than arrest. He was sentenced to 40 hours of community service.

Huerta was clearly resisting the deputies but Tulare County jurors, generally regarded as pro-prosecution, apparently found his response reasonable considering the amount of force directed at him.

The deputies have denied they improperly targeted Huerta. They say he might have presented a danger to his elderly mother because he pushed her away from the door shortly after deputies started banging on it. She testified in the criminal trial that her son had never been abusive and she never felt endangered.

Huerta’s mother, Josefina, testified that she kept telling the deputies that it would be better to settle the matter the next day.

Tulare County Sheriff Mike Boudreaux issued a written statement about the Huerta matter in 2017.

“There are two sides to every story,” he told the Valley Voice newspaper in Visalia. “You have heard one side. Our side, which involves a personnel matter, will be heard during litigation.”

“At this time there is no evidence to support the allegation,” the sheriff continued. “Due to the pending litigation, we are unable to elaborate on our position … .”

Boudreaux’s office said in March and again in April that the sheriff will have no additional comment until after the civil trial.

Lack of body cam footage ‘doesn’t look good’

D’efending the deputies has been a complicated task for the county. That’s partly because of the apparent seriousness of Huerta’s injuries and the body camera issue.

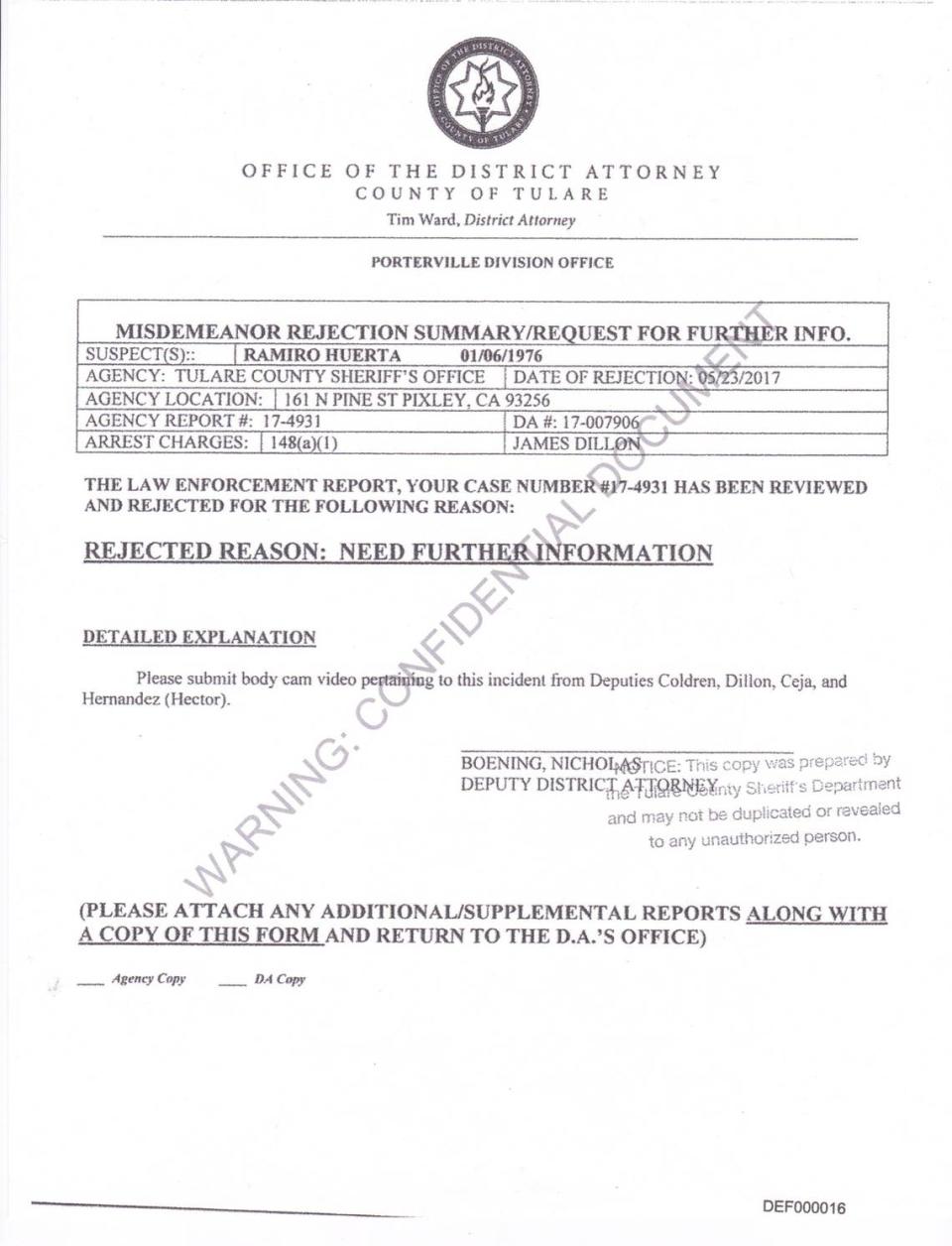

The Sheriff’s Office sent a set of incident reports to the District Attorney’s Office as part of a request for criminal charges. The prosecutors’ initial reaction was to formally reject the request because no body camera footage had been submitted.

During Huerta’s resisting arrest trial, prosecutor Andrew Kosch acknowledged that the lack of body cam footage “doesn’t look good” but said there were innocent explanations.

Huerta’s lawyers have been trying to establish that the deputies were instructed to turn off their cameras before confronting Huerta. The deputies have testified, however, that there were legitimate and innocent reasons for the sparse footage. Those included mechanical malfunction, forgetfulness and a mistaken impression that the action had already ended. Lt. Smith testified in Huerta’s misdemeanor trial that he never told the other men to turn off their cameras.

California doesn’t require law enforcement agents to wear body cameras while engaged with the public but it is the policy of a growing number of agencies to require them. The Tulare County Sheriff’s Office is one of them.

Lt. Smith testified at Huerta’s trial that his own body cam was under repair. He said those were the early days of body cams and getting them to work involved a lot of trial and error.

Body camera technology has improved since then. Smith testified he was skeptical of their value at first but now, “I love them” because the video removes doubt about what occurred.

It could prove significant that one of the defendants in the federal litigation, Deputy Salvador Ceja, was later disciplined for hitting a handcuffed juvenile in Pixley after asking his partner to turn off his camera. Ceja testified in Huerta’s trial that he had simply forgotten to wear his camera on the day of Huerta’s arrest. Ceja is no longer with the sheriff’s office.

Deputy Michael Coldren said he experienced a hardware problem; the connection between his radio and camera had failed. Coldren was later promoted to detective before moving briefly to the Visalia Police Department. He has since left law enforcement.

Correctional Officer James Dillon IV and Deputy Hector Hernandez said their body cameras were functioning early in the confrontation but they turned them off prematurely when they incorrectly thought the action was over. Their cameras captured some of the deputies’ initial contact with Huerta.

Those deputies are defendants in the federal civil rights case along with Deputy Laura Torres-Salcido, who allegedly taunted Huerta over his homosexuality while he was being treated at a Porterville hospital later that night. She has denied that.

‘It was a beatdown,’ veteran sheriff’s official says

An expert witness for Huerta testified at the trial that the deputies blundered by making no effort to deescalate the situation when they arrived at his front door while a couple of body cameras were operational.

“Well, if you watch the body-worn camera, you know, I mean the officers’ conduct was very aggressive and assertive from the very beginning,” said Jeff Noble. Formerly a deputy police chief in Irvine, Noble has been certified as an expert witness in more than 30 trials.

“Officer Hernandez admitted that he called Mr. Huerta a jackass, told him to shut up,” Noble testified. That was shortly after Huerta reportedly used the same term to describe a deputy.

“People don’t comply and they don’t have to comply with our commands,” Noble continued.

Noble said it appeared the deputies immediately chose to make the visit a confrontation rather than a legitimate welfare check.

“It was a beatdown,” says a veteran sheriff’s official, since retired. “It was an ambush.”

That source spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation. He was not there that night but says he heard disturbing descriptions of the encounter from deputies and one of their supervisors.

Sexual identity an issue? ‘Only open gay in town’

Huerta says he thinks he was targeted because he isn’t deferential to law enforcement and possibly because of his sexual identity.

“I’m probably the only open gay in town,” he said. He feels like a lone wolf in Strathmore, population 3,000 or so and declining. Like many San Joaquin Valley farm towns, it has been struggling because of drought, COVID and its high poverty rate. Most blocks in the little business district have at least one boarded-up store.

Huerta has lived there with his parents since 2012. He grew up near the Boardwalk in Santa Cruz, where his parents ran a florist shop. He says he spent many of his high school days hiding from other students.

“I was different,” he said. “I wanted to hide.”

After high school, he moved to Southern California. He worked in florist shops in Huntington Beach and Venice and then owned his own in Malibu.

He lived in Visalia for several years before moving to Strathmore after his sister, Sandra, a high school counselor, died in childbirth. The trauma of it all almost broke his parents, he remembered.

The house is filled with the stuff of everyday life plus his mother’s squawking birds and yappy dogs. Outside, front and back, it’s a jungle, tropical despite Tulare County’s freezing winters. Huerta proudly shows off the foliage.

He’s a fairly big fellow, 6-foot-3 and about 210 pounds though one of the deputies testified that he seemed heavier in 2017. Huerta says he has never been arrested but has had words with law enforcement officers over the years. He said he had some things to say several years ago when deputies ignored his reports of shots fired in the neighborhood.

“I don’t understand their mentality about service,” he said. He also said he doesn’t like the way law enforcement treats Latinos. During the filmed portion of his confrontation with the deputies, he complained that his family was “being treated like wetbacks.”

The federal lawsuit contends that the deputies were taunting Huerta for being gay, name-calling that allegedly continued after he was taken to the hospital.

The lawsuit says that during Huerta’s brief stay there a nurse asked if he was “a top or a bottom.” That’s a reference to homosexual practices.

County officials have denied that Huerta was targeted because of his race or sexual orientation.

The lawsuit alleges that the deputies “mocked Huerta and accused him of ‘hiding behind his mother.’ The officers were clearly there to teach Huerta a lesson. Huerta and his mother were frightened. … (They) informed the deputies and officers that nothing was wrong and that they did not wish to open the screen door as there was no warrant.”

‘Goon squad’ behavior, one attorney contends

After the deputies pretended to leave, the lawsuit continues, Huerta walked into the front yard and was “tackled from behind by an officer who had been hiding in the bushes.”

Other deputies joined in, the lawsuit contends, and Huerta was dragged back into the house where he was “repeatedly punched and kicked in the face by numerous officers with heavy boots. In addition he was struck repeatedly with batons.”

The lawsuit says Huerta was then handcuffed and dragged back outside where he was pepper-sprayed, loaded into the back of a patrol car and beaten some more.

During the annoying-calls trial of Huerta, another of his lawyers, Boris Treyzon, also called the incident a beatdown. He also said he believed it may have been requested by the dispatchers who had taken Huerta’s calls.

Treyzon said the deputies felt they were just doing their job but simply went too far.

“They don’t get to be a goon squad,” he told the jury. “They don’t get to threaten us when we call to complain about what they do.

“They don’t send one officer. They don’t send two officers. They send four officers and a sergeant to check on what they consider to be somebody who maybe … may be under the influence of alcohol and drugs. Not drunk. Somebody in the confines of their home may have taken medicine or consumed alcohol.

“That’s five men with guns, batons, a massive flashlight, (who) showed up at his house hours after he called.”

After almost no treatment at Porterville’s Sierra View Hospital, Huerta was taken to a holding cell late that night. He was released the next morning but didn’t have a ride, so he walked home 13 miles away, barefoot, through the orchards of Tulare County.

Two days later, his father drove him back to the hospital because blood was coming out of his mouth and nose.

Reflecting the importance of the civil case and the potential for a significant judgment, 12 lawyers were involved at last count, five on Huerta’s side and seven representing the county.

Freelance writer Royal Calkins is a former Bee reporter and editor of the Monterey Herald. He writes regularly for the Voices of Monterey Bay website.