When It Was the Beatles’ World and We Just Lived in It

The story of the Beatles did not end happily. Break-ups are seldom cheerful. But it was not, as some of us thought at the time, the end of the damn world.

Craig Brown tells that story in 150 Glimpses of the Beatles, from the early days to 1970, when the four members of the band went their separate ways. But what Brown does best is remind us why the split did seem at the time—to Beatles fans at least—like the end of everything.

I don’t know if Brown’s is one of the best books written about the band because I’ve never managed to finish a book about them, but it’s one of the best books I’ve read on any subject in a good while.

With a handful of exceptions (the autobiographies of Keith Richards and Count Basie, Nick Tosches’ book about Jerry Lee Lewis), I’ve never been too interested in books about bands or musicians, even ones I like. I picked up Brown’s book because I’m a huge fan of his last book, 99 Glimpses of Princess Margaret. I had never been much of a royals fan either, but I thought, well, I’ll try a glimpse or two and see how it goes. In no time, Brown hooked me for the whole ride. He did it again with the Beatles.

Brown is not, as you may infer from the word “glimpses,” a straight biographer. He’s more of a literary collagist, scouring old news accounts and more conventional Beatles books, drawing on the experiences of his own childhood, searching for the odd anecdote or illuminating incident that hasn’t been told to death and then stitching all these stories into a roughly chronological sequence.

The Beatles’ Secretary, Good Ol’ Freda, Breaks Silence in Exclusive SXSW Interview

What amazed me right off, especially given that I’m no expert on the lives of these men, was how much of the story I knew before I began reading. If, like me, you were a child edging into adolescence when the Beatles became famous, you’ve had these people in your life forever, not like kin but certainly not strangers. Without even trying, you know at least the vague outlines of their personalities (prickly John, professional Paul, etc.) and the major turns of their lives (Apple records, the Maharishi, Yoko). Knowing about the Beatles was like knowing about the O.J. Simpson case: You didn’t have to read the news or watch TV to keep up; on the contrary, you couldn’t escape the details if you tried (I once rode in a Dublin taxi driven by a man with a seemingly encyclopedic knowledge of all things O.J., and an unquenchable desire to share.)

Clearly, this could make for a boring read, if even I knew a lot of the story going in. But this is where Brown’s cleverness and originality make all the difference. For example, instead of the usual biographical slog through the band members’ childhoods, he takes us along as he tours the childhood homes of John and Paul, which are now under the protection of the National Trust and restored to look as they did when the Beatles were boys (there’s absolutely nothing original or genuine about the furnishings, but you can’t have everything). Brown’s tours of these homes quickly degenerates into hilarious combat between the tourist and his tour guides, a husband and wife with decidedly proprietary notions about “secret” Beatle facts that only they know and can share—but which Brown points out are widely available on the internet. The result is a win-win: you get a look at recreated childhood environments that, however unlikely, incubated genius, and you also get a good loony dose of the covetous, possessive, doctrinaire nuttiness that afflicts so many keepers of the flame in Beatle land.

Brown begins and ends his book with the Beatles’ manager Brian Epstein, and this is entirely apt, for while he does not say so explicitly, Brown implies, correctly I think, that before and after Epstein, the Beatles were adrift.

At the outset, he chose their clothes and haircuts and issued them printed directions on behavior and decorum, and all four Beatles, even John, meekly followed orders. Not much changed from the day he met them in 1961 until his death by overdose (ruled accidental but pretty clearly suicide) in 1967. Epstein was their rudder. Not himself creative, he seems to have understood creativity, and he gave them the room they needed to grow. The day Lennon heard that Epstein had died, he would later recall, “I knew that we were in trouble then. I didn’t really have any misconceptions about our ability to do anything other than play music… I thought, ‘We’ve had it now.’”

It was a eulogy more for the band than the manager, but it proved accurate. Within three years, the Beatles would break up, and the road to the break-up, post Epstein, was the dark mirror to their gleaming, inexorable ascent with him at the helm.

The secret to Epstein’s success was that he was as much a fan as a manager: He loved the Beatles as much as we all did and in much the same way.

“Everything about the Beatles was right for me,” he said in a 1964 interview. “Their kind of attitude to life, the attitude that comes out in their music and their rhythm and their lyrics, and their humor, and their personal way of behaving—it was all just what I wanted. They represented the direct, unselfconscious, good-natured, uninhibited human relationships which I hadn’t found and had wanted and felt deprived of.” I think practically every kid I knew growing up felt exactly the same way.

Paul McCartney, George Harrison, John Lennon & Ringo Starr of the Beatles, taking a dip in a swimming pool, 1964.

Brown succeeds because he’s not trying to write a definitive Beatles biography. Instead, he recreates what it was like to live through Beatlemania, whether you were a besotted teen or a skeptical adult. This is a hard thing to convey to anyone born after the ’60s, because while all four Beatles still walked the earth after the break up, and even though their music would become an unshakeable part of the culture, the sense of seismic change, the sense that you could not escape them—that all went away pretty fast. And it’s that nearly indescribable craziness that Brown brings back to life so vividly.

The history of the Beatles, that is, the history of the group, is not a tragedy, but it is a story where their most intense joy is largely front-loaded. On Jan. 17, 1964, Brian Epstein burst into the band’s suite at the George V Hotel in Paris and said, “Boys, you’re number 1 in America.” The single in question, “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” would sell a quarter of a million copies in three days and go on to sell 5 million copies in the U.S. The night they heard the news from Epstein, the Beatles bounced not only off the walls but every other surface in their hotel suite as well, including a bed where they wound up in a celebratory pillow fight and threw Ringo in the air for good measure.

Brown ends Glimpse 38 with the slightly melancholy question, “Would they ever again be so deliriously happy?” The answer, as even the most inattentive Beatles fan knows well, is probably not.

Call this a cut-and-paste book if you must, but that’s a hideously reductive judgment. Yes, Brown has read his way through countless biographies and news accounts, culling details and rearranging them in his mosaic retelling of the band’s career. But he is no hack, and he knows just where to position himself between his source material and the reader. He is less like an Ed Sullivan, an impresario showcasing acts, and more a Joseph Cornell, the artist famous for his vitrine-like boxes that magpied disparate elements (old photographs, tiny ladders, rubber balls) and from them constructed dreamy, surreal little realities as unsettling as they were entrancing.

Brown may not be one of those change-your-life writers, but I can’t think of anyone else whose books provide more fun per page.

“The Beatles shone so brightly that anyone caught in their beam, no matter how briefly, became part of their myth,” Brown writes, and he makes his point by going down a number of rabbit holes (if this whole book could not be called a collection of rabbit holes) to showcase the fans, the performers with whom the Beatles shared a stage, the narc who tried so zealously to bust them but wound up more Inspector Clouseau than Inspector Javert.

Fan letters are low-hanging fruit to any self-respecting biographer, but while Brown may be shameless, he also has taste and he only picks the best fruit.

What It Was Like to Watch the Beatles Become the Beatles—Nik Cohn Remembers

Dear Ringo,

YOU ARE THE HANDSOMEST MAN IN THE WORLD, EXCEPT FOR MY FATHER.

MY FATHER IS HANDSOME TOO, IN AN OLD WAY.

Love,

Norma A.

Denver, Colorado

Dear Beatles,

I told my mother that I can’t imagine a world without the Beatles, and she said she could easily.

Loyal forever,

Lillie K.

Fairbanks, Alaska

Dear Beatles,

Please call me on the Telephone. My # is 629-7834

If my mother answers, hang up. She is not much of a Beatles fan.

With love from,

Maxine M.

Cleveland, Ohio

Dear Beatles,

I am a loyal fan. I have every one of your records and I don’t even have a record player.

Love, Donna J.

Portland, Maine

Dearest John,

I would like a lock of your hair. Also, a lock of hair from George, Paul, and Ringo. You know you have plenty of hair, so you can spare one lock each for me.

With love,

Sylvia M.

New York City

P.S. Please write the name of the person on each lock, so I will know who the lock of hair belongs to, as it is hard to tell when it is not on a person’s head.

Had she gotten her wish, Sylvia M. might be considerably richer today: in 2016, a lock of Lennon’s hair was auctioned for 35,000 pounds.

Hair, of course, was always integral to the Beatles’ story and sometimes, in the case of fights between parents and children, the story. Hair was certainly the obsession for Madame Tussauds: “September 1968 marked the fifth time in four years that the technicians felt obliged to update the Beatles’ waxworks to allow for their ever-changing appearances; three months later Paul grew a beard, and they had to start the process all over again.”

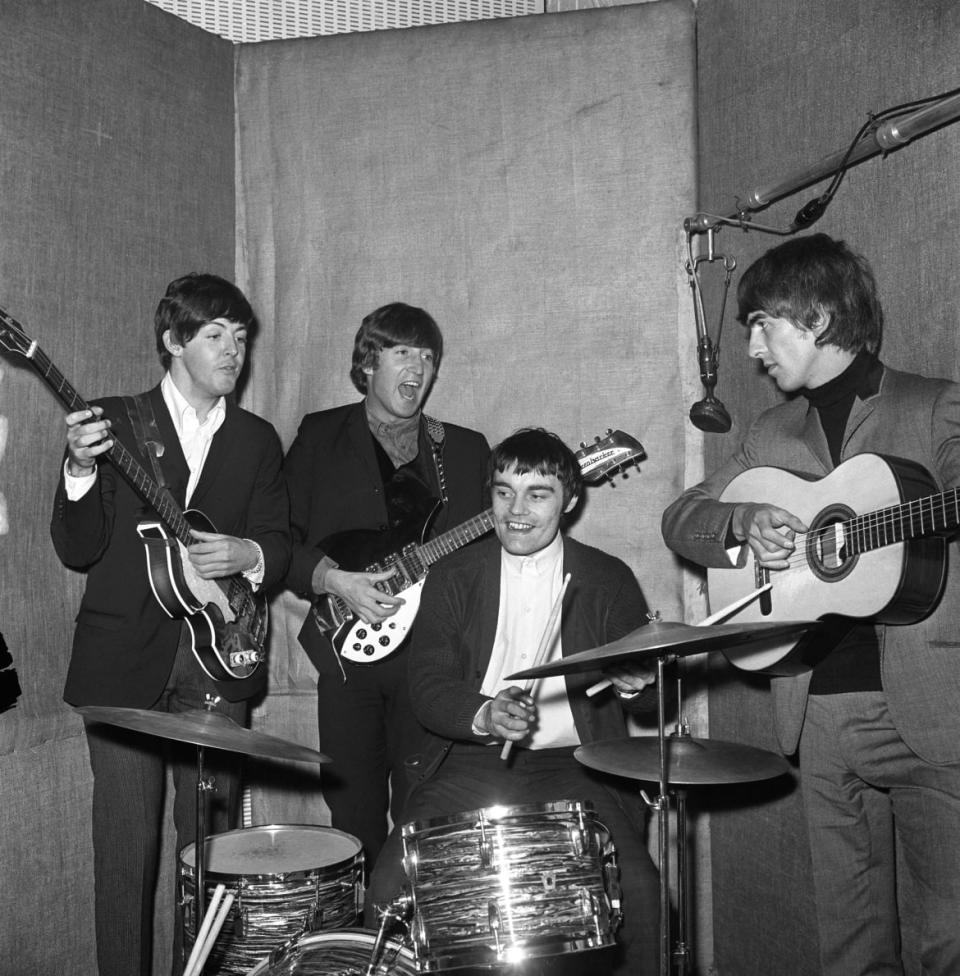

Of the supporting players profiled by Brown, none is sadder than Jimmie Nicol, the drummer who joined the band for a few days on a 1964 world tour while Ringo recuperated from a tonsillectomy. Nicol had been obscure before he got a call from George Martin inquiring as to his immediate availability, and to obscurity he returned once his temp gig was done, although not without a futile attempt to jumpstart his career on the basis of having been, however briefly, a Beatle. He recorded a few singles, they failed to chart, and slowly, painfully, Nicol returned to the shadows. In a 1965 Daily Mail interview, he complained that sitting in for Ringo “was the worst thing that ever happened to me. Up to then I was feeling quite happy, turning over 30 to 40 pounds a week. I didn’t realize that it would change my whole life… But after the headlines died, I began dying too.”

Being one of those journalists who head for the losers’ locker room after the big game, Brown uses the occasion of the Beatles’ appearances on The Ed Sullivan show to profile one of the hapless acts that shared that famous bill.

Mitzi McCall and Charlie Brill, a young comedy act, came on near the end of the show, right before the Beatles’ second appearance. Stoked for weeks at the thought of making their debut on the Sullivan show, McCall and Brill realized that the sophisticated comedy routine they’d rehearsed for weeks was DOA as soon as they stepped on stage. Performing for an audience of teenage girls who had not come to see them, they bombed. And they knew it even as it was happening. Or, as Brill put it, “We were up there for two years.”

Drummer Jimmie Nicol, 24, who is filling in for Ringo Starr after he collapsed during a photographic session at Barnes Studio.

Unlike Jimmie Nicol, McCall and Brill were singed but not incinerated by their close encounter with the Beatles. Eventually they got their career back on track, although it did take their agent six months after the Sullivan show before he phoned.

And the immediate aftermath was agony. To recuperate, they headed down to Miami Beach, where two weeks later, as they were walking to their car one night, a limousine pulled alongside. “Inside were the Beatles, there for a second appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show, which was being recorded at the Deauville Hotel.” John Lennon recognized them and asked, “What are you doing here?”

“Escaping from you,” they replied.

Hardcore Beatle fans may be annoyed by this sideshow stuff, but I would argue that the sideshow is integral. The Beatles did not exist in a vacuum, and they did change everything they touched, and by everything I mean all of us who lived through their time together as a band, but also musical taste, fashion, hair length, even spirituality (meditation might be the common practice it is today without the Beatles, but they certainly were the ones who goosed it onto the main stage). We were all part of the story. Some of it was silly, some of it was dark, but most of it was oddly and unexpectedly magical. Before reading this book, I would have said you had to be there to understand it, but Brown has brought it all back and made it available to one and all. In much the same way that the Beatles musically recreated, eulogized, and forever preserved the real Penny Lane in song, 150 Glimpses of the Beatles lets us relive what it was like to happily share the planet for a few years with a band like no other before or since.

OK, not happy for everyone: Harry Bioletti, the barber “showing photographs of every head he’s had the pleasure to know” in “Penny Lane,” was not much of a fan, at least not once the men whose heads he’d once barbered when they were the Quarrymen started letting their locks go long: “I’ve taken their pictures down,” he said in 1967, when “Penny Lane” was released. “Such hair is bad for trade. I’m not disloyal, but business is business. I encourage plenty off the top in my shop.”

Got a tip? Send it to The Daily Beast here

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.