Are Beaufort Co. plantations ‘leisurely’ or racist symbols? It helps to know our history

Most times Hilton Head native islander Alex Brown leaves his house, he drives by graves and a historical marker that bear the names of the men who enslaved his ancestors.

He cringes.

For 220 years, Brown’s family has lived on land that was once the Chaplin Plantation. But even if his neighborhood were called that, Brown would never use the name.

“I don’t tell anyone that I live in Chaplin Plantation,” he said. “I would have a huge problem with that just because when my forefathers were living on that plantation, they did not have the rights and freedom that I currently do.”

More than 100 years after crops withered and slaves were freed, some gated communities in Beaufort County still use the word “plantation” in their names to denote status, safety and, to Brown, exclusivity.

This week, renewed debate about whether this word should be removed from Beaufort County vernacular or chiseled off the communities’ signs coincides with a national conversation and enhanced awareness by white people of police brutality, racism and the history that surrounds us.

At least 4,300 people have signed a petition saying the county’s resorts and gated communities — some populated almost exclusively by white residents — should not be called plantations.

And at least one property owners’ association will take up calls from members to scrub the word from the development’s name.

The issue dredges up a painful past for some and disdain of political correctness for others. Managers of some communities balk at how expensive or intricate removing the word would be. Some say to erase the name erases an important history. Others say it’s nearly impossible to correct 50 years of legal documents.

“For someone to wave their hand and say ‘change the name,’ that is not something that is taken lightly,” Hilton Head Plantation general manager Peter Kristian said. “(Plantation) was to denote a leisurely lifestyle and to recognize the history of the land.”

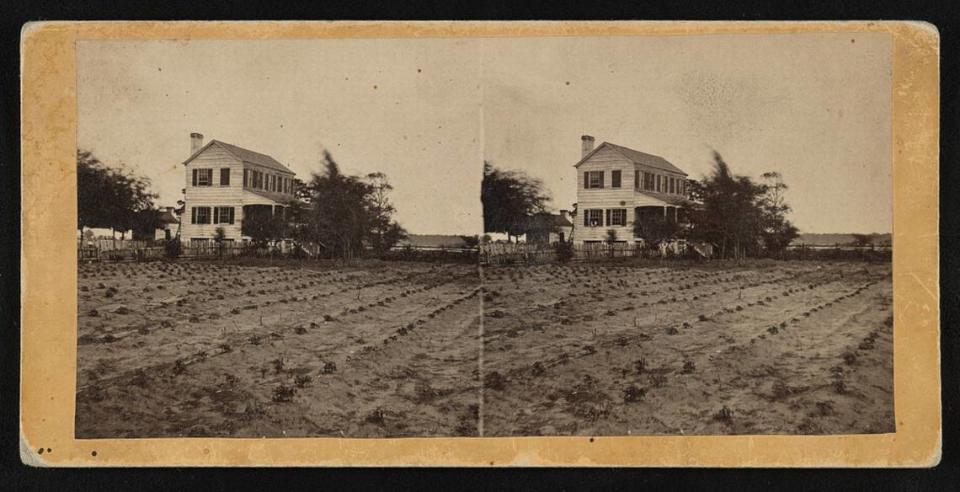

As modern-day million-dollar homes sit just yards from the foundations of plantations that once enslaved hundreds of Black people, who gets to decide what history matters most?

Were Beaufort County communities plantations?

South Carolina was established as an agricultural colony in 1670, and 50 years later, people of African descent made up two-thirds of the colony’s population, according to historical census data.

They didn’t arrive by choice.

Charleston, known as the “Ellis Island of Black America,” was the largest slave port in the United States. For over a century, African people were both shipped into and brought down to Beaufort County to work on rice, cotton and vegetable plantations.

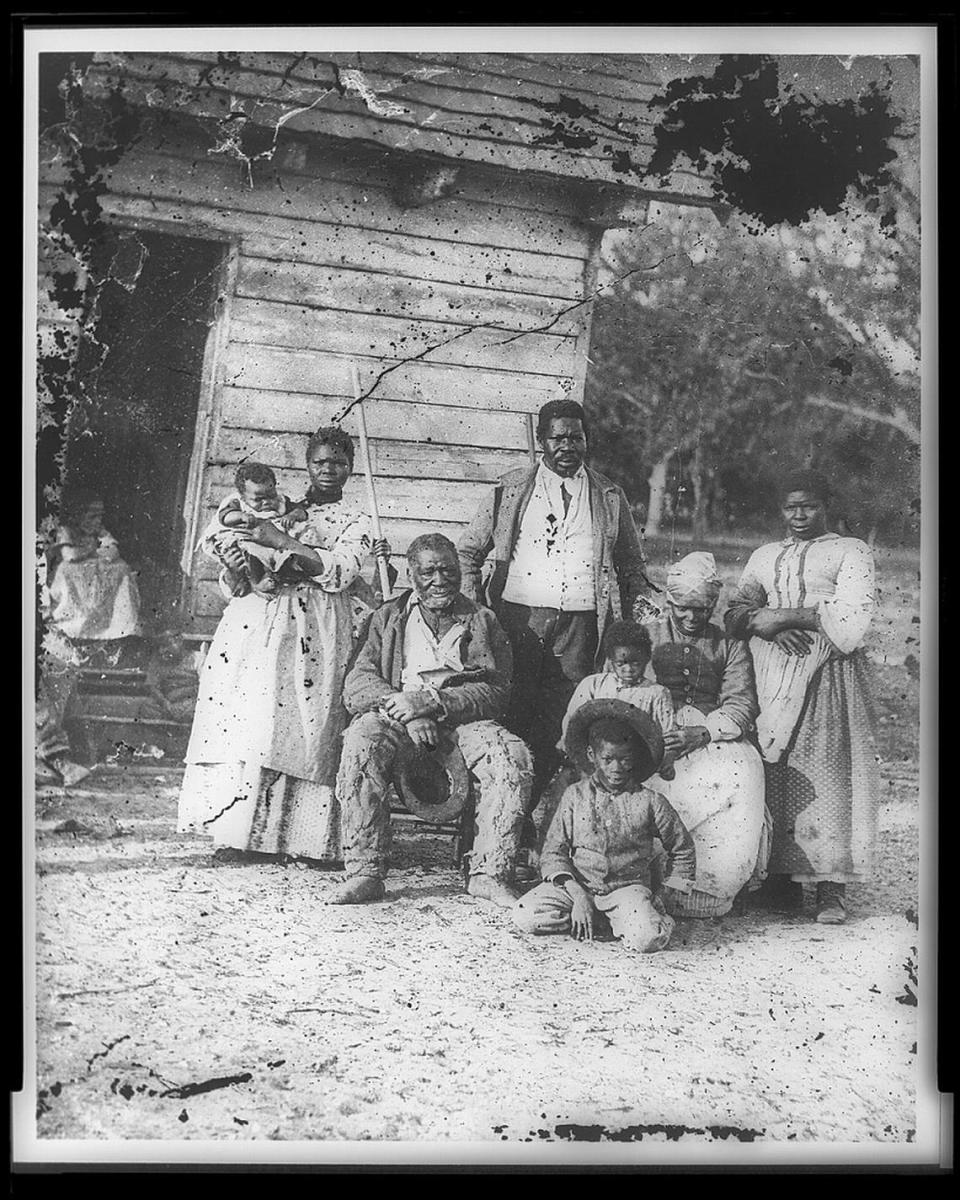

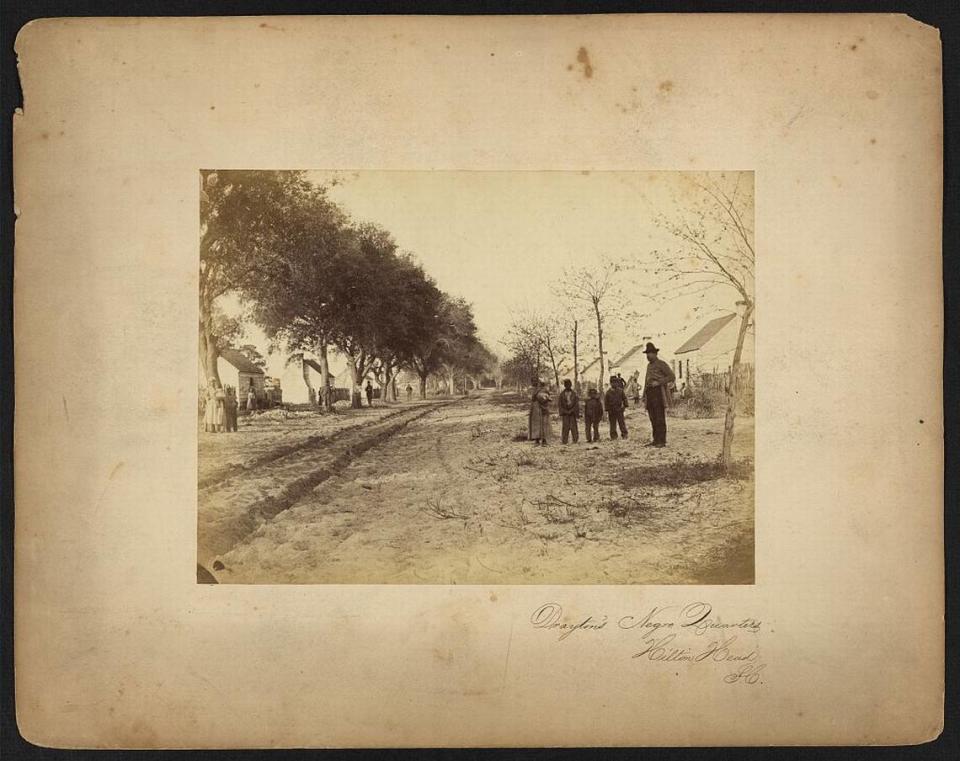

Enslaved people worked long hours in brutally hot conditions, exposing themselves to yellow fever, malaria and cholera. They toiled in knee-deep mud clearing swamps for rice cultivation. Oral histories recorded in South Carolina include memories of physical violence and sexual abuse by plantation owners.

But the plantation system made Beaufort County one of the wealthiest areas in the United States.

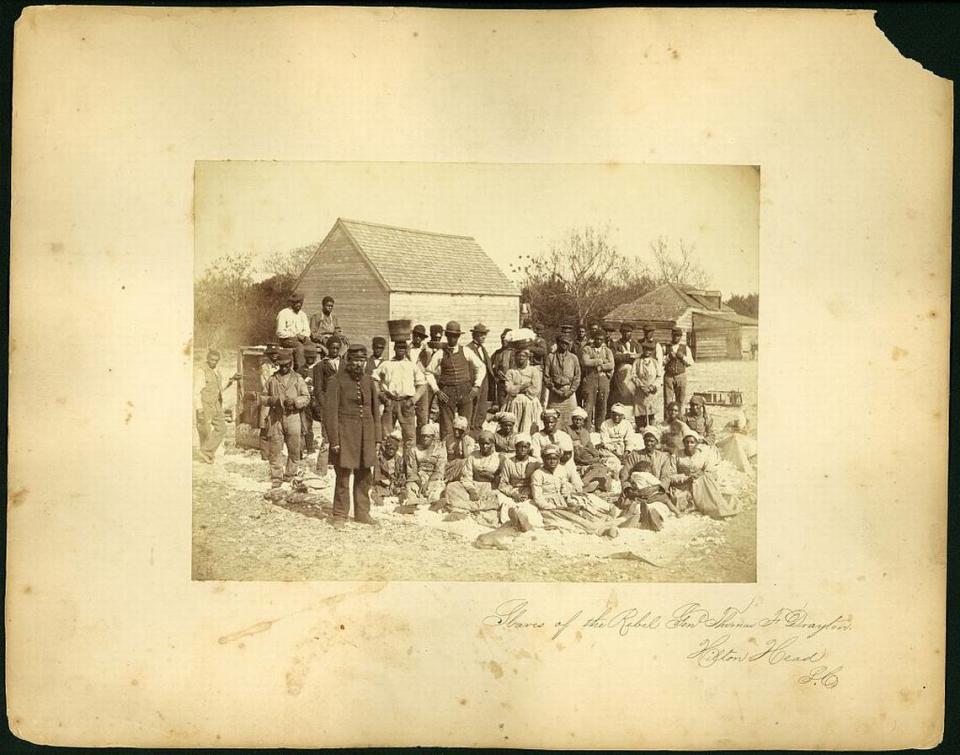

Just before the Civil War, Beaufort was the “Newport of the South.” Then, 81% of the county’s population was enslaved Black people, according to 1860 census data.

While the idea of the “plantation” originated in the extension of English colonial reach, in South Carolina the term was explicitly tied to slavery.

The “planters” were a class of landowners who also owned at least 20 slaves, and the term “plantation” signaled a large farm worked by enslaved labor, according to James Tuten, a historian at Juniata College in Pennsylvania who is a Hampton County native and has studied Lowcountry rice plantations.

“Owning a plantation and being named as a planter or being understood that way in the 18th and 19th centuries in the South absolutely granted you prestige and implied power and economic wealth,” Tuten said.

Some historians refer to Southern plantations as “slave labor camps,” emphasizing the violence and degradation of human rights that took place there.

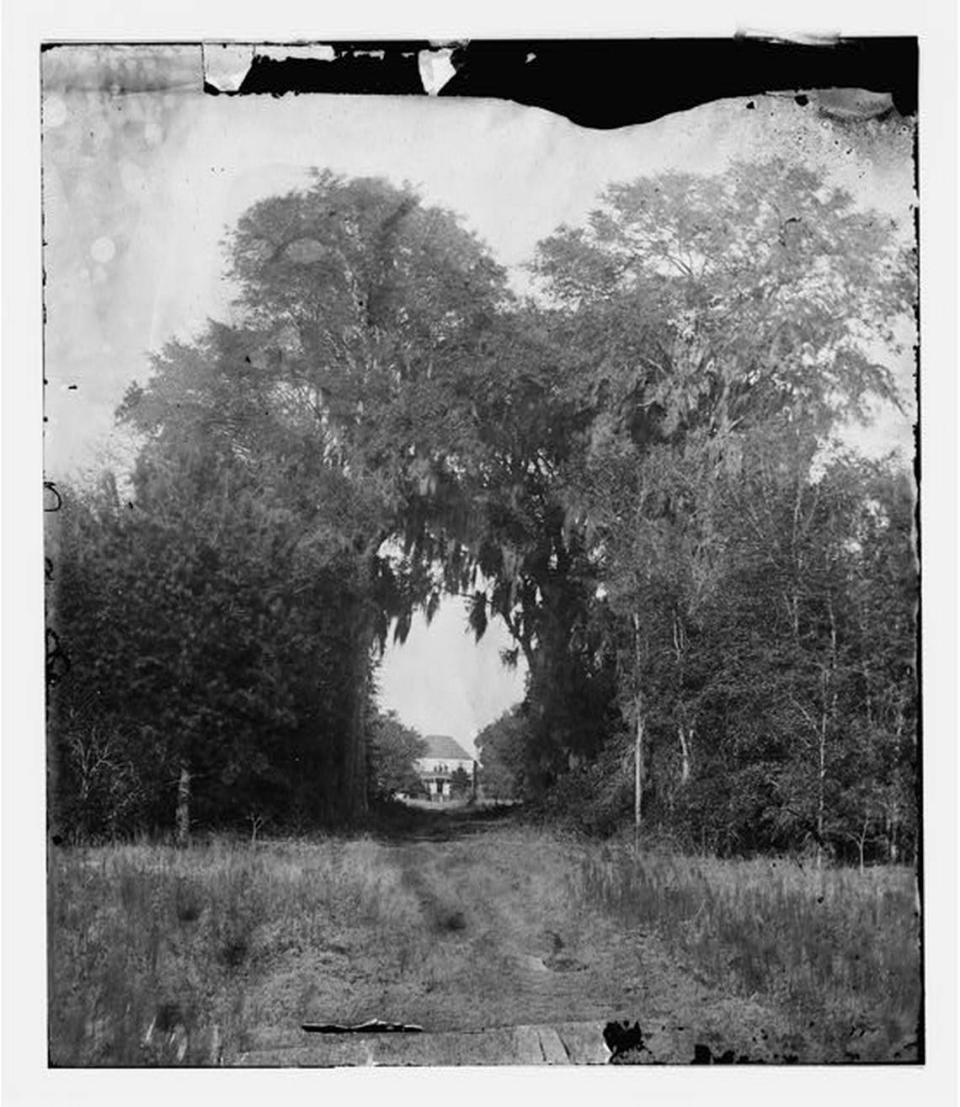

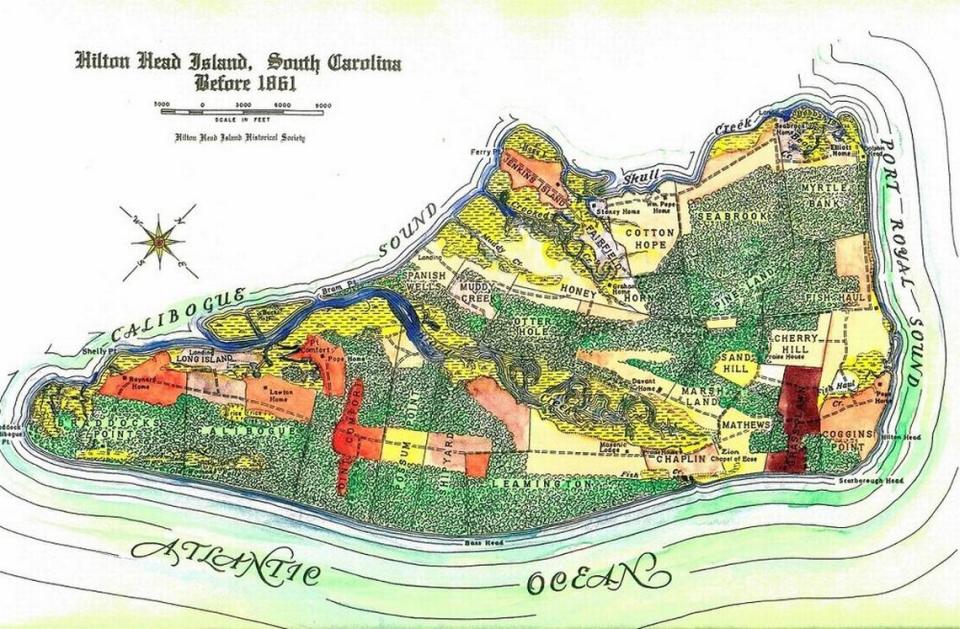

On Hilton Head, plantations changed hands countless times. The Heritage Library’s maps recognize between 20 and 24 plantations owned by 16 families that dominated the island. In many cases, their borders fall eerily close to those of modern-day gated communities.

As Union troops claimed Beaufort County’s Sea Islands, Hilton Head saw the first freedom experiments in the United States. Mitchelville became the first self-governing community for freedmen, and people who once worked the land as slaves became the landowners.

The history of Mitchelville, Gullah-Geechee foodways and language lives on in Hilton Head’s historic neighborhoods, where generations of islanders have fought for sewer connections and freedom to use their land how they please.

Following the turn of the 20th century, “plantation” began to take on a whole different meaning for white people. Gone were the days of planting and domestic service. But even as rice and cotton lost their profitability, plantations kept their allure, often as hunting preserves for well-off northerners.

The modern concept of the “residential plantation” paints planters in positive terms, Tuten said.

“It largely obscures or forgets about slavery, and it emphasizes instead their refined sense of taste,” he said.

Native islander Brown said the word’s meaning changed on Hilton Head when the island’s agriculture industry was replaced “with a new crop” — tourists.

To attract wealthy northerners to the island, Charles Fraser’s Sea Pines Plantation had to stand out with displays of wildlife and gripping promises of southern charm in 1957.

“The word ‘plantation’ then connoted a very different meaning to the audience Charles (Fraser) was talking to,” said Hilton Head Town Council member David Ames, who worked alongside Fraser. “It was a marketing decision on Charles’ part.”

Following Sea Pines’ lead, developers established private communities that now stand on the same soil as Myrtle Bank, Seabrook, Coggins Point, Shipyard, Spanish Wells, Muddy Creek and Braddocks Point Plantations — words that still exist today in the form of neighborhoods and street names.

“What’s left of the plantation is the land, the landscape, and the associated prestige and the pursuit of leisure ... that was always a part of the image to white people of what the plantation was,” said Tuten.

Twenty years after Sea Pines’ establishment, The Island Packet’s founding columnist, Jonathan Daniels, remarked in the newspaper’s pages that the word “plantation,” then excluded from a new sign erected outside Shipyard, “has certainly been overworked on this shore as a euphemism for subdivision or development.”

Selling the plantation

As modern-day neighborhoods are named to evoke ideas of relaxation and safety, the word “plantation” doesn’t embody that idea to Black Hilton Head native islanders.

“It denotes the old labor system: Labor camps where people lived in plantations in comfort and others worked in discomfort,” Gullah community leader and historian Emory Campbell said. “Today’s use of that word … it really brings to mind that period in history.”

And the word sticks out to others.

When Dave and Lavonne Hales arrived on the island from Illinois in 2009 to buy a home in Hilton Head Plantation, they said they were offended to see such a charged word on island signage and marketing materials.

“We moved down here because we thought it was such a beautiful place and people were very nice, but that was just the one thing: the word ‘plantation,’” Lavonne Hales said. “Our family was a little taken aback when we told them where we were moving.”

The couple said they’re organizing with friends and neighbors to lobby their POA board representatives. They want to change the name as soon as possible.

“Hilton Head Plantation is a leader on this island, and it should have been a leader on this issue,” Dave Hales said. “Our general manager and board need to stand up and make the decision.”

Campbell said the Hales’ experience is shared by the millions of people who come across Hilton Head Island’s bridges.

“People come from all over the world here, and given the U.S. history with slavery and segregation, it hits them in the face like nothing has changed,” he said.

Painful past or ‘mountains out of molehills?’

Most of the exclusive communities that bear the plantation name today don’t represent the diversity of Beaufort County.

The census tract covering the southern tip of Hilton Head, inside Sea Pines, is 97% white, according to the latest U.S. Census Bureau figures. The two tracts covering Hilton Head Plantation and Palmetto Hall are 99% and 98% white.

Beaufort County is no longer majority African American, as it was for hundreds of years.

“It is not a pleasant history for us as Black people,” Campbell said of plantation-era South Carolina. “Whether you’re white or Black, I think you’re on the right side of history when you say that word is offensive to human beings.”

Some who have commented on the issue online say they oppose removing the word “plantation” because they see the change as empty symbolism that does little to address structures of racism or change individual behavior.

Also mixed into the over 300 Facebook comments last week on an Island Packet editorial on the subject were commenters who chastised people for taking offense to the word and others who said striking it from the county’s communities is akin to erasing history.

Carol Casey, who moved to Hilton Head from Ohio nearly 40 years ago, said she never felt like she was glorifying slavery when she lived in Hilton Head Plantation.

“History is history, (removing “plantation”) doesn’t change it,” she said. “’Plantation’ doesn’t mean anything bad today, and that’s not what I think they thought of when they were putting together plantations on the island.”

Casey said she “thought about the loveliness of a southern plantation,” when she was deciding where to live.

Her thinking shows how the meaning of the word “plantation” changes throughout history and even among generations. Casey said she disagrees with the removal of Confederate monuments and frequently discusses it with her grandchildren, who see the issue differently.

“They’re just making mountains out of molehills,” she says of young people who want to remove references to plantations on Hilton Head.

What would change look like?

For Beaufort County’s gated communities that have committed to dropping “plantation” from their names, the decision was “just the right thing to do.”

But other community leaders frame the change as a costly task requiring overwhelming support from members — as well as the destruction of a decades-old brand.

The issue last arose in earnest following tumultuous months in 2015 when a North Charleston police officer gunned down Walter Scott, white supremacist Dylann Roof murdered nine African American people during a church Bible study in Charleston and South Carolina officials lowered the Confederate flag from the statehouse after mass demonstrations.

The church shooting, in particular, sparked discussion among board members at the Colleton River Club in Bluffton, then named Colleton River Plantation.

“Like others, it touched our community, and its members,” said Jim Humphrey, then board president.

In a meeting, the POA board discussed whether “plantation” was an essential part of the community’s name and, deciding it was not, committed then and there to remove it, said Humphrey.

“For us, it was just the right thing for our club to do,” he said, adding that members were pleased with the decision.

Other communities have removed the word from their names without much pomp and circumstance. On Hilton Head, Indigo Run Plantation removed the word when it changed ownership in 2000. It became the Indigo Run Community Owners’ Association, a switch leaders said was not very difficult.

“Once the community became self-governed, they incorporated without the name ‘plantation,’” general manager Cary Kelley said. “I’ve managed communities that have changed their name. All it really took is a legal filing.”

Indigo Run did not revise its existing deeds, so while many property owners’ legal documents still list Indigo Run Plantation, the word has not been used in business transactions after 2000 and is not on the community’s sign or in its branding.

The community sits on land once occupied by Otter Hole and Honey Horn Plantations. Information about how many people were enslaved there is not available, but a 1920 map shows a double row of slave houses on Otter Hole Plantation, according to a Chicora Archaeological Survey of Portions of Indigo Run Plantation.

Sea Pines also changed the name of its community to drop the word “plantation.” Town Manager Steve Riley said the company removed Fraser’s original name sometime in the 1980s, when it split to separate commercial and residential entities.

Sea Pines sits on 5,200 acres of land where the Stoney-Baynard, Braddocks Point and Calibogue Plantations once stood. Ruins from the Stoney-Baynard Plantation house still attract visitors to the community. The plantation enslaved 129 people as of 1861, according to the Chicora Foundation Research Series, In the Shadow of the Big House.

In other communities that still use the word, property owners would have to OK such a change, following procedures outlined in restrictive governing documents that demand near-unanimous approval.

“Changing the name of a community like Hilton Head Plantation is not an overnight task,” general manager Kristian told The Island Packet. “It will be a very costly task, too. Hundreds of thousands of dollars.”

Kristian said his community would survey its residents next year to gauge general interest in a name change. If they had a quorum to call a vote, 75% of the community would need to vote in favor to change the community’s bylaws.

To then amend the community’s covenants, a separate vote would be needed in which 67% of the community would have to vote for the change. Hilton Head Plantation achieved this majority in 2019, when the community voted to ban some short-term rentals.

“Hilton Head Plantation is a brand. It’s known throughout the world for the brand; people buy here because of that brand. You’ll need to associate a new name with the brand,” Kristian said. “That is going to be a monumental [public relations] undertaking that would be very costly to the property owners.”

The land on which Hilton Head Plantation sits today was once three plantations: Myrtle Bank, Seabrook and Cotton Hope. Around 1810, the three combined with the Stoney family’s nearby Fairfield Plantation to form Skull Creek Plantation, where 156 people were enslaved in 1832, according to Robert Peeples’ Tales of the Ante Bellum Hilton Head Families.

Palmetto Hall and Wexford, both on Hilton Head Island, also use the word “plantation” on their signs. Neither communities’ administrative staff returned calls about their use of the word.

Bull Point Plantation in Sheldon said in an email that its board was “looking into this issue,” but didn’t comment further. Staff at Brays Island Plantation did not return a request for an interview about the community’s use of the word, and POA board members at Pleasant Point Plantation didn’t return messages sent through their website and passed through an associated property management company.

Two Hilton Head gated communities — Leamington and Shipyard — carry names of the plantations that once stood on the same land, although neither uses the word “plantation” on its signs.

Leamington was owned by the Pope family from 1793 until it was confiscated by the government around the time of the Civil War. Nearby Shipyard, owned by the Fickling family, was named after the family’s ship-building business. Information about how many people were enslaved there is not available.

Elsewhere on Hilton Head, the word “plantation” has been taken off marketing materials but remains in the legal name of some communities.

Residents in Port Royal, known legally as The Association of Landowners of Port Royal Plantation, have brought the issue to their property owners’ association a handful of times in the past seven years, general manager Lance Pyle said.

His community doesn’t use “plantation” on its sign, but all of the documents associated with home deeds and covenants do.

“If somebody’s goal is to eliminate the word ‘plantation,’ you have 50 years of documentation you’ll have to change,” he said. “If someone makes a change going forward, it would be more reasonable.”

Port Royal Plantation was once Coggins Point, Grass Lawn and Fish Haul Plantations, which were owned by the Pope family. The Pope House, built in 1806, was used as the headquarters for the Department of the South during the Civil War. Squire William Pope owned 200 slaves, according to the 1860 agricultural census.

The history of the land may not be top of mind, though. Pyle said that although the community values its war-related relics, such as the Port Royal steam cannon, he was unaware that the community sits on soil once occupied by plantations.

“We’ve looked at our history as our war memorials that are still here,” he said. “That’s the history we are probably most familiar with.”

‘Not going to solve our issues’

Nationwide calls for racial justice and against police brutality following the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police have motivated some gated community residents to take up renaming where they live. Crystal Higginbotham, general manager of Rose Hill Plantation in Bluffton, said a handful of members reached out this week about changing the name.

In the years before the Civil War, James Brown Kirk ran Rose Hill as a cotton plantation, enriching his family and at one time enslaving over 250 people, according to a historical summary published on the community’s website.

The community’s board will take up the issue at its next meeting, she said, and any change would have to be approved through a community-wide referendum. Higginbotham said in 2015 the appetite to change wasn’t strong.

“After the circumstances we’re under right now and the things that have been brought to the surface, people may have a change of heart,” she said.

That change of heart is what many are counting on, but the passion and outrage incited over the word “plantation” is just the start of a larger conversation native islander Brown wants to have about race, inequity and land use in Beaufort County.

“If they remove ‘plantation’ or not, that’s not going to solve our issues,” Brown said. “That does not change someone who feels they are less than another, or someone who feels they are more than another.”

“That’s the root of it that needs a lot of attention,” he added.