'They behave like barbarians': Ukraine's chief war crimes investigator sees few prospects for reconciliation with Russians

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

KYIV, Ukraine – As Russia has escalated its use of imprecise Soviet-era missiles against civilian infrastructure, Ukraine's top legal official said she doesn't see how ordinary Ukrainians and Russians can reconcile until Moscow "asks for forgiveness, pays reparations to the state" and ensures "all its war criminals are in prison."

Prosecutor General Iryna Venediktova was speaking exclusively to USA TODAY from her office in Ukraine's capital, where she is coordinating the work of hundreds of Ukrainian and international war crimes investigators and specialists. Her aim is to hold Russia's military and senior officials accountable for alleged indiscriminate missile strikes and shelling, civilian assassinations, torture, sexual violence, repeated assaults on hospitals, and denial of food, water and humanitarian aid.

Four months after Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine, in a major escalation of a war that began in 2014, many cities across the country are still being pounded daily by Russian air and sea strikes, rocket artillery and cluster munitions.

But last week, Russia appeared to step up its bombing campaign and carried out especially deadly assaults on civilian targets.

On June 27, a Russian missile struck a busy shopping mall in Kremenchuk, in central Ukraine. At least 20 people were killed. Two dozen people are still missing. That same day, Russian forces shelled central areas of the eastern city of Kharkiv, killing five and wounding 22. Three days later, at least 21 people were killed when Russian missiles hit a residential apartment building and two resorts near Odesa, Ukraine's port on the Black Sea.

Authorities said Russia fired outdated missiles that lack precision on the Kremenchuk mall and in Odesa.

Venediktova, 43, is from Kharkiv, a predominately Russian-speaking city in eastern Ukraine.

"I have a Russian last name. I know many people there. And I know that many ordinary Russians seem to support (President Vladimir Putin's) policy to kill ordinary Ukrainians," said Venediktova, a former law professor. "For me, it's been a shock to see this, and a really big question is: How is this generation (of Russians) ever going to look Ukrainians in the eye after all these actions? They behave like barbarians."

Venediktova insisted that her remarks should be attributed to "Iryna Venediktova the Ukrainian citizen, not Iryna Venediktova the prosecutor general," a job broadly equivalent to that of the U.S. attorney general.

"The pattern of Russia's military behavior (throughout history) is ... brutality," she said, adding she believed Thursday's attack on Odesa "looks like revenge" after Russia's military abandoned its positions on Snake Island, a tiny rocky outcrop off the coast of Odesa that has become a symbol of Ukrainian resistance.

Oleksiy Goncharenko, a Ukrainian parliamentarian who chairs Odesa's regional legislature, said there is "a lot rage about Russians."

"We are absolutely furious with them, and for many of us there is a presumption of guiltiness, not innocence, as far as Russian war crimes go," he said. "And if they want to be cleared of this they should take a position. They need to publicly say: 'I am against this war and these atrocities.' Only if Russians start doing this can we start talking with them again."

Goncharenko said he will travel to Washington in mid-July to give war crimes testimony at a congressional hearing.

Biden on Ukraine: Biden vows U.S., NATO allies will stand with Ukraine 'for as long as it takes'

Accusations against Russia, which denies war crimes

Russia denies targeting civilians and rejects claims of war crimes despite a large and growing dossier of physical, visual and verbal evidence. Russia's military has long been accused of targeting civilians in conflicts in Chechnya, Georgia and Syria, as well as in Crimea and the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine.

Soviet soldiers were notorious for engaging in brutalities on civilians during and after World War II. These included rape, civilian murders and plunder. Millions of Ukrainians died in a famine engineered by Josef Stalin's government in the years leading up to that war.

Ukrainian history: What is the Holodomor? A brief history of the deadly famine in Ukraine many call genocide

Looks like a huge fire burning here in #Kharkiv tonight after an apparent Russian missile strike. Photo sent to me by a fireman on the scene now pic.twitter.com/ZBN4XBNYp9

— Kim Hjelmgaard (@khjelmgaard) June 28, 2022

Given state censorship, biased pollsters and the Kremlin's efforts to control domestic perceptions of the conflict, it's difficult to gauge what ordinary Russians really think about Putin's unprovoked war in Ukraine. But survey data released in early June by the Levada Center, perhaps Russia's only remaining independent pollster, found that 77% of Russians back the war despite widespread accusations of war crimes against its military and Ukrainian claims that about 35,000 Russian soldiers have perished.

At least 4,700 civilians have been killed since Russia invaded Ukraine on Feb. 24, according to the United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, though the actual civilian death toll may be far higher.

Over the weekend, Russian forces captured Lysychansk, the last city in the Luhansk region in eastern Ukraine that was still under Ukrainian control. President Volodymyr Zelenskyy vowed to take back the area with the help of heavy weaponry.

As many as 10,000 war crimes in Ukraine

Virtually every major Ukrainian government department is involved in documenting suspected war crimes, including its border control, local and national police, military and domestic intelligence agencies, interior ministry, defense department and a broad array of specialized security and emergency services. Ukrainian civil society groups and networks of domestic and foreign volunteers also are collecting information.

Ukraine wants to try the majority of war crimes cases in its own courts, though some higher-profile cases could wend their way to the International Criminal Court in the Hague, Netherlands, which claims universal jurisdiction for war crimes.

Several European countries have opened their own separate investigations. The U.S. Justice Department may seek to prosecute suspected war crimes cases involving the killing or wounding of U.S. journalists in Ukraine, Attorney General Merrick Garland announced during a visit to Ukraine on June 21, when he met with Venediktova.

Venediktova told USA TODAY that each day in Ukraine the number of war crimes cases is increasing by a "huge number," and the total number of cases has now likely exceeded 10,000. More than 100 suspects have been identified, most of them low-ranking Russian soldiers. Six cases have already been tried.

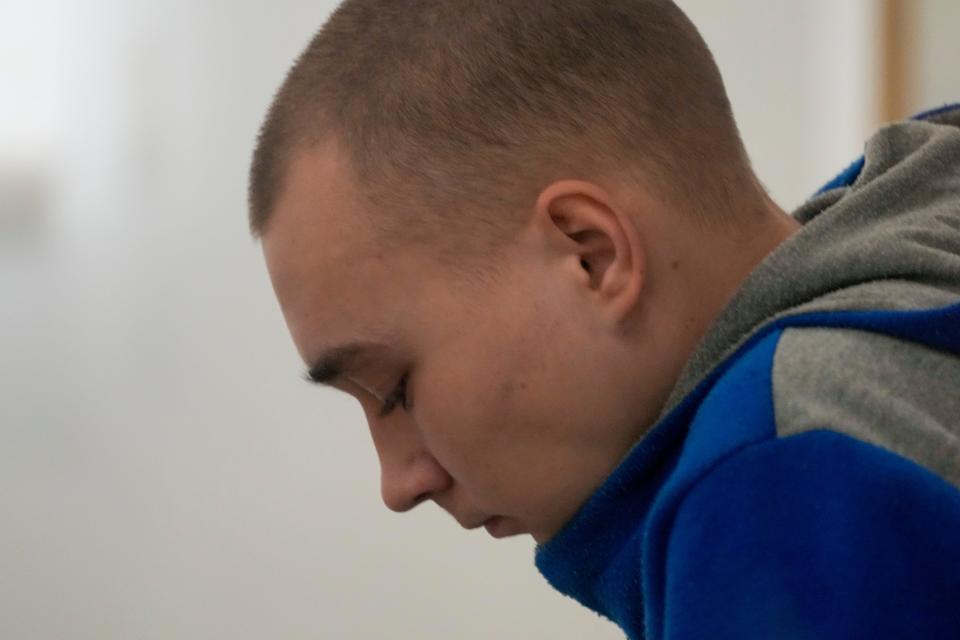

Army Sgt. Vadim Shishimarin, 21, the first person to go on trial, was sentenced to life in prison for killing Oleksandr Shelipov, 62, in the northeastern village of Chupakhivka on Feb. 28. Shishimarin fired his Kalashnikov at Shelipov through an open car window, killing him as he walked his bike on the sidewalk and talked on the phone.

Venediktova said Ukraine also will eventually seek to prosecute more than 600 top Russian officials – cabinet ministers, senior military commanders and propagandists – for the "crime of aggression," an international statute recognized by the ICC, though not the U.S., that says it is a crime to invade, attack, annex or bomb another country. These proceedings would almost certainly take place "in absentia," meaning the accused would not physically stand trial because they are in Russia.

Russia's veto power on the U.N. Security Council means the international organization can't establish a formal tribunal, but the U.N. is investigating suspected human rights abuses in Ukraine.

She said it's possible some Russian war crimes suspects in Ukraine could be swapped for Ukrainian prisoners of war held by Russia, and she expressed concern over the prospect of yet-to-be-discovered atrocities in Russian-occupied territory.

Hunting to kill Russians?

Maj. Gen. Kyrylo O. Budanov, the chief of Ukraine's military intelligence, told USA TODAY late last month that Ukrainian operatives have already started hunting to kill Russian military personnel they believe are responsible for war crimes in Ukraine – "torturers," as the Ukrainians call them.

"Amid the fog of war sometimes the Russians cannot clearly differentiate if a person just died in a battle or if there's been a targeted assassination," Budanov said. He said such operations also have taken place inside Russia, successfully targeting midranking Russian officers.

Venediktova in the interview said she had no knowledge of such operations. She also expressed surprise over the idea that they could be taking place.

She has been Ukraine's prosecutor general since March 2020. Since the war's outbreak, she has been constantly on the move, visiting suspected crime scenes, meeting with high-level foreign officials and appearing on TV. Flanked by her security detail, she is often seen in a bulletproof vest and army green fatigues.

Venediktova was appointed by Zelenskyy to help reform an office critics say is plagued by inefficiencies, and several of her predecessors were removed from the role under clouds of suspicion connected to corruption allegations in a country that has struggled to shake off perceptions of graft in public life.

Exclusive: Ukraine's top military spy says U.S. fighters could be released in swap

She is the first woman in Ukraine to hold her job.

"Ukraine unfortunately is not an easy place to work for women," she said.

"If we're talking about Russian war crimes and aggression, I know exactly what I need to do. I know I need to coordinate all the law enforcement agencies, all the experts. ... I never reflect on myself as a women in this job. For me, the hardest part of my job is actually to speak with Ukrainian journalists and civil society because it's clear they don't look at me as a prosecutor general. They look at me as a woman, and not in a good way. In Ukraine a woman needs to work 10 times as hard as a man."

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Ukrainian official: 'Huge number' of Russian war crimes committed