What’s behind the rise in plasma centers in San Joaquin County? What you should know

On his fourth plasma donation appointment in Stockton, Santiago Lopez, 25, sat in a wide reclining chair under fluorescent lights, surrounded by dozens of strangers.

Like Lopez, they’re all careful not to move the needles in their arms.

He scrolls on his phone as the apheresis machine takes his blood, spins it around, and returns the red cells back into his arm. The machines’ dull hum fills the room.

“I’m three weeks out of work, so I’m donating. The 50 bucks I get helps me sleep comfortably,” Lopez said. “It takes a lot out of you, so I probably won’t come back again until after the holidays.”

Lopez, like other Stockton residents, is taking advantage of plasma donation centers as they continue to pop up in the northern San Joaquin Valley.

As access to healthcare improves around the world, new technologies are doing a better job of diagnosing immunodeficiencies, blood and protein disorders, leading to an increasing number of patients who require therapies.

The increasing number of patients requiring plasma-derived therapies has created a need for more donation centers; primarily in the U.S., the largest global supplier of plasma.

San Joaquin Valley residents who live in low-income areas say they benefit financially and personally from plasma donation centers near them.

Commercial plasma collection can pay enough to cover monthly bills and boost local economies, while also giving people the opportunity to help someone in need.

On the other hand, studies show the global plasma industry is worth billions of dollars, and barely a fraction of that money makes its way back into the hands of donors.

“I know (plasma) is probably worth way more than what they give us,” Lopez said, “but no one’s going to say no to 50 bucks. The way I see it, people who (donate) are in a bad place. But, hey, it’s better than stealing.”

The basics of plasma – and why it’s so valuable

Plasma is valuable to the medical community because it cannot be manufactured. The yellowish liquid is mostly water filled with infection-fighting antibodies. It makes up half of all blood volume to help move other blood cells within the body.

Plasma is used for procedures and therapies in cosmetic, emergency and life-prolonging situations.

Plus, plasma-derived therapies help immunodeficient individuals, like cancer patients and others who can’t make their own antibodies.

It helps those patients live normal lives. In hospitals, plasma transfusions are also used to prevent shock in trauma patients.

A growing industry

As the demand for plasma rises, more centers are popping up.

In 2022, two commercial donation centers opened on March Lane in Stockton. Another has begun construction in Modesto, with plans to open in January.

For over 50 years, Stanislaus and San Joaquin counties have been home to American Red Cross/Delta Blood Bank locations. Red Cross acquired Delta Blood Banks in Stockton, Modesto and Turlock in 2013.

Centers across the nation pay people anywhere from $30 to $70 per donation.

Payments can reach $100 or more per donation when companies offer promotional prices, like during holiday seasons, or as referral bonuses.

In order to donate, you have to be at least 18 years old, weigh at least 110 pounds, and test negative for hepatitis and HIV, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Doctors or physician substitutes are required to conduct extensive medical history screenings and physicals before you can donate.

Donors should be aware there is not a lot of information on long-term effects of plasma extraction.

Experts say the potential risks for the process are low, but comprehensive and independent studies of patients who donate the maximum amount are rare and difficult to conduct because companies are not required to share data with local governments.

There are two types of plasma collection centers: for-profit and nonprofit.

For-profit companies have the ability to pay hundreds of dollars for donations. Nonprofit organizations compensate donors with small gifts like T-shirts or gift cards, but do not pay donors for their plasma.

In Stockton, donors have the options of CSL Plasma or BioLife Plasma companies and the American Red Cross.

Modestans and residents living in the region will be getting a BioLife Plasma center in McHenry Village in January. They also have Red Cross donation centers in Modesto and Turlock.

BioLife, with its locations in the U.S. and Europe, does not sell plasma for emergency use in hospitals, but collects it for its parent company Takeda Pharmaceutical Company. Takeda produces over 20 plasma-derived therapies.

CSL, an international company, sends its plasma out to create therapies used in over 100 countries, a spokesman said in a statement.

Commercial plasma centers are becoming more popular, but often do not directly give back to local communities. For-profit plasma companies generally ship plasma to pharmaceutical labs and out of the country.

Local hospitals depend on voluntary donations from non-profits.

San Joaquin General Hospital exclusively receives all its blood products, including plasma, from the American Red Cross, spokeswoman Hillary Crowley said.

“All blood product donations are handled, collected, and processed by Vitalant, a blood supplier to Kaiser Permanente Central Valley,” spokesman Jordan Scott said in a statement. Kaiser Permanente has locations in Stockton, Manteca, Tracy and Modesto.

St. Joseph’s Medical Center in Stockton also utilizes Vitalant, spokeswoman Kellie Ryan said.

The nearest Vitalant locations to San Joaquin and Stanislaus counties are in Sacramento, Merced.

Ethics of the industry

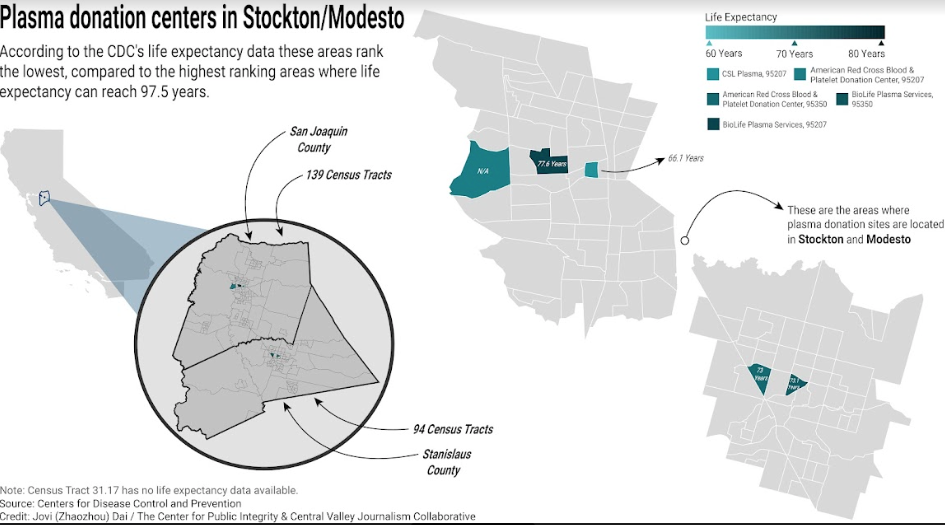

In Stockton and Modesto, plasma donation sites are mostly found in areas with the lowest income and life expectancy rates, according to U.S. Census data.

There is no denying this trend is targeting a class of people most likely to need extra money.

Commercial centers, whose collective market value is over $30 billion and on the rise, are not required to share their data on the age, race and sex of plasma donors with local governments or health organizations to ensure fair and safe treatment as they harvest plasma.

Stanislaus County does not have this information, spokeswoman Kamlesh Kaur said.

Collection of data is crucial for researchers to see how different kinds of people react to plasma donation. As of today, this is not possible.

Plasma donation centers, both for and nonprofit, aren’t required to submit any data to Stanislaus County Health Services unless donations are found to violate Title 17 of the California Code of Regulations, Kaur said.

After an initial inspection required to open a plasma donation center by the California Department of Public Health, the agency doesn’t specify the time between routine inspections of facilities.

BioLife cited patient privacy for its inability to release generalized data on San Joaquin Valley residents. CSL Plasma’s international spokesman ignored the request altogether.

Some donors say they prefer going the nonprofit route, particularly those that have an established track record.

For example, Joanne Azevedo, a retiree from Ceres, said she has exclusively donated plasma to the Red Cross on Orangeburg Avenue in Modesto for nearly a decade.

“I just think the companies may not do what’s best for you when money is involved,” Azevedo said when asked why she chose to donate to the Red Cross instead of a commercial center.

“You wouldn’t know when (companies) cut corners. I know it’s healthy here, that the Red Cross wouldn’t do anything underhanded,” she said.

Regulations for nonprofit plasma donation are more strict than commercial donations. Nonprofits allow donors to return once every 28 days, up to 13 times a year with some flexibility.

Commercial donation centers allow donors to return twice in any 7-day period, but no more than once in a 48-hour period, according to the U.S. Health and Human Services Department.

The process can take anywhere from 45 minutes to three hours, depending on your hydration levels and other factors.

No matter how often you donate, experts say it’s safe if a medical professional gives you the green light.

Common reasons to be turned away by a plasma center depends on how you answer questions about traveling to countries flagged by the FDA, sexual history, chronic illness, and even recent surgeries, tattoos and jail time.

According to the Department of Health and Human Services, serious infections or reactions can occur when donating, which can be treated. The most common side effects are lightheadedness,fatigue, bruising, bleeding, and dehydration.

Studies of frequent plasmapheresis (plasma) donors have not shown that these donors report more infections, or any other health-related problems, than the average population, American Red Cross Divisional Chief Medical Officer Dr. Courtney Lawrence said in an email statement.

You can learn more about plasma donation and its importance through the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Zhaozhou Dai, data reporter with The Center for Public Integrity & Central Valley Journalism Collaborative, contributed to this report.

Vivienne Aguilar is the health equity reporter for the Central Valley Journalism Collaborative, a nonprofit newsroom based in Merced, in collaboration with the California Health Care Foundation (CHCF).

This article originally appeared on Visalia Times-Delta: What’s behind the rise in plasma centers in San Joaquin County?