Behind the signs: 15 unique markers that detail Nashville’s history

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

NASHVILLE, Tenn. (WKRN) — Nashville has slowly changed over time as new structures are built, old ones are torn down, and businesses have come and gone, but little pieces of history remain throughout the city.

Those stories are told through the over 1,000 historical markers scattered throughout Nashville and Davidson County, with one of the earliest markers erected by the Metropolitan Historical Commission of Nashville and Davidson County in 1968.

How Nashville’s once extensive streetcar system became a thing of the past

The program was started just one year earlier to commemorate significant people, places and events in the city’s past, and according to the commission, it has been one of their longest-running and most successful programs.

As of 2023, the Metro Historical Commission has erected just under 300 markers across the county. Many more have been erected through the Tennessee Historical Commission’s Historical Marker Program, which began a few decades earlier in 1948.

State and local markers are differentiated by seals at the top, with state markers having three stars and local ones bearing the Metro seal. Each contains accounts chronicled by academic historians.

According to the Tennessee Historical Commission, the state’s marker program initially reflected the experiences and issues most relevant to a small minority — almost all male, white and affluent — with other important narratives missing.

Retro Nashville: Explore Music City history

However, in the years since, the marker program has been broadened to reflect the experiences and contributions of Black Americans, Native Americans, other people of color, and women.

Some markers in Nashville may currently be down because they were damaged or were removed during construction in the area. The Metro Historic Commission conducted its last marker assessment survey from 2018 to 2020 to assess the condition of all markers.

Below is a list of some of the unique historical markers you can find in the area. Missing or damaged markers can be reported to the city by calling 615-862-7970, or if it is a state marker, 615-770-1093.

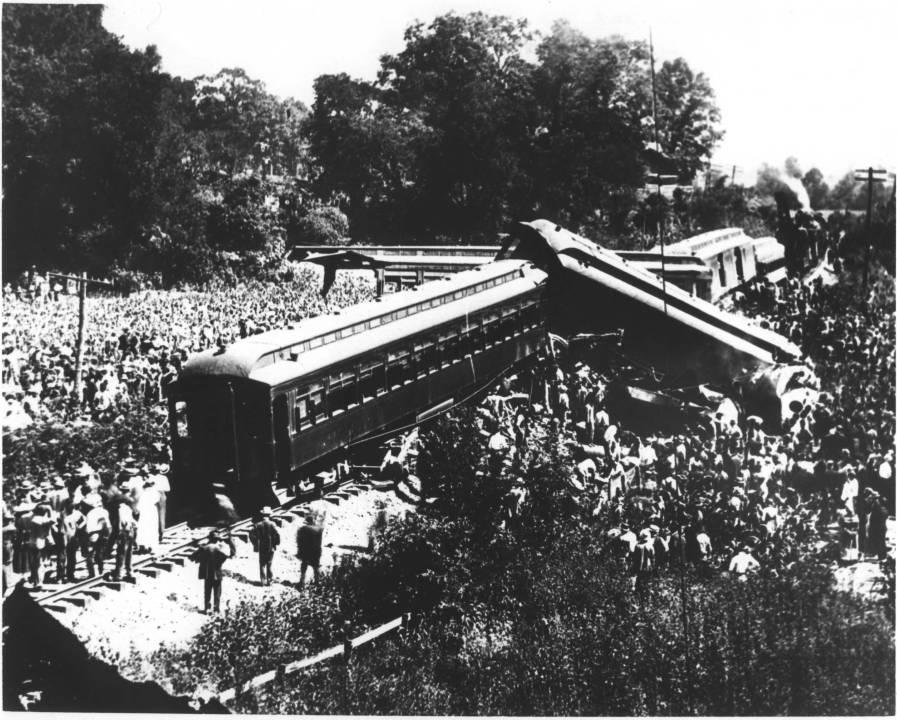

Dutchman’s Curve Train Wreck

This marker, which was erected by the Historical Commission of Metro Nashville and Davidson County in 2008, sits on the site of one of the deadliest train wrecks in U.S. History.

On July 9, 1918, two crowded trains collided head-on at Dutchman’s Curve. The impact caused passenger cars to derail into surrounding cornfields and several fires broke out throughout the wreckage.

Over 100 people died, including many Black workers who were journeying to work at the munitions plant near Old Hickory. The marker is located on White Bridge Pike, just 0.1 mile east of Post Road.

Jesse James House

After robbing a bank in Northfield, Minnesota, the infamous bank robber, Jesse James, and his family lived in a house on Fatherland Street in Edgefield for nearly four and a half years between 1876 and 1881.

‘Athens of the South’: How the Parthenon became an iconic part of Nashville

A member of James’ gang was captured in the Whites Creek area of Davidson County. During his stay in East Nashville, James went by the name “J.D. Howard.” The marker is located at the intersection of Russell Street and South 9th Street in Historic Edgefield.

The Seeing Eye

Located on 3rd Avenue North in Downtown Nashville, this plaque marks the site of The Seeing Eye, the world-famous dog guide training school, which was the first to train dogs to be service animals for the assistance of the blind.

The Seeing Eye was incorporated in Nashville on Jan. 29, 1929, with headquarters in the Fourth and First National Bank Building at 315 Union Street. Morris Frank, a 20-year-old blind man from Nashville, and his guide dog Buddy, played a key role in the school’s founding and success.

It was Frank who reportedly persuaded Dorothy Harrison Eustis to establish a school in the United States. The marker was erected in 2009 by the Historical Commission of Metro Nashville and Davidson County.

Centennial Park Swimming Pool

Opened in 1932, the Centennial Park pool served Nashville’s white community as a premier swimming facility for nearly 30 years. However, city officials abruptly closed the pool in 1961 after two Black student civil rights activists led an effort to desegregate the facility.

How Tootsie’s Orchid Lounge became one of Nashville’s most famous honky-tonks

The city responded by closing all Nashville public pools, blaming the sweeping closures on budgetary concerns. While many neighborhood pools reopened in 1963 under the newly consolidated metro government, the Centennial Park facility sat vacant for 10 years.

To some it was a daily reminder of the city’s racial divide. The pool’s bathhouse was renovated and reopened as Centennial Art Center on April 23, 1972. The former shallow end of the swimming pool is preserved as a courtyard in the rear portion of the building.

The Jungle and Juanita’s

Warren Jett opened The Jungle, a restaurant and cocktail bar, at 715 Commerce Street in 1952. Next door, Juanita Brazier opened Juanita’s Place, a beer bar, in 1956. By the early 1960s, both were known as the first gay bars in Nashville.

Music City Mixtape: 12 places to explore Nashville’s musical history

Jett sold The Jungle in 1960 after his brother, Leslie Jett, was elected sheriff. In 1963, 27 men were arrested for “disorderly behavior” in a raid at Juanita’s. Gay men continued to gather at both bars until 1983, when the block was leveled.

The historical marker, which was erected in 2018, can be found on Commerce Street, just east of Rosa L. Parks Boulevard in Downtown Nashville.

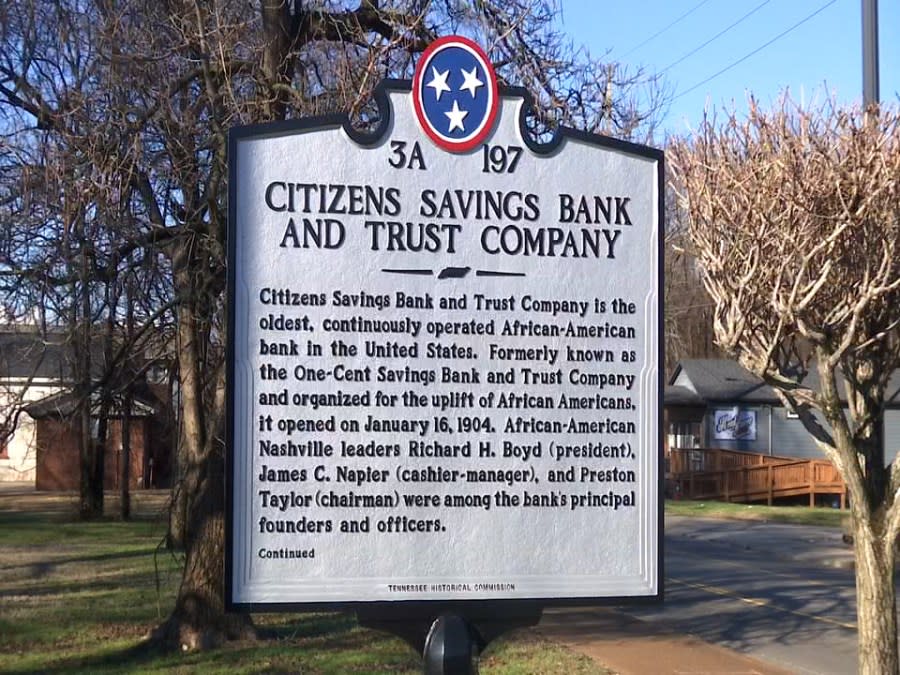

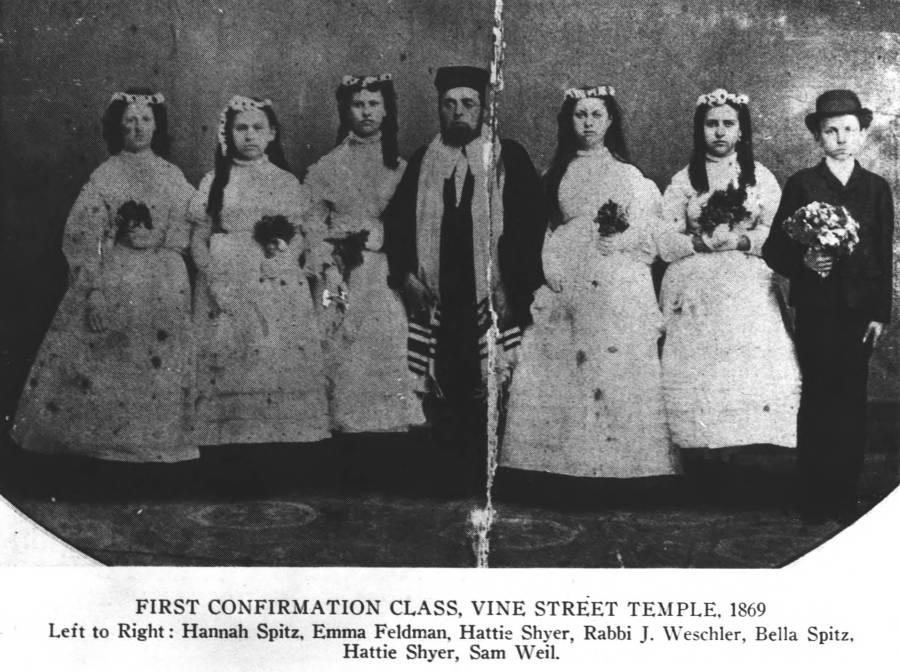

Vine Street Temple

Completed in 1876, the Vine Street Temple with nine Byzantine domes was Nashville’s first synagogue, and for 80 years, stood as a symbol of the city’s strong Jewish presence. The city’s Jewish community began in the 1840s.

Many early families were immigrants fleeing oppression in Germany, Russia and Poland. In 1955, the Reform congregation moved the temple to West Nashville, where it and other Jewish congregations continue today.

The historical marker, which was erected in 1990, is located at the intersection of Commerce Street and 7th Avenue North in Downtown Nashville.

Club Baron

Built in 1955 during the golden age of Jefferson Street’s music scene, which lasted from 1935 to 1965, Club Baron is the only extant nightclub from that time. The building also served as a secondary location for Brown’s Pharmacy, as well as the only skating rink for Black Nashvillians.

Riding the nostalgia wave inside Opryland USA

The club is best known as the site of a 1963 guitar duel where Nashville bluesman Johnny Jones bested up-and-comer Jimi Hendrix. Other well-known performers include Fats Domino, Etta James, Little Richard, Otis Redding, Muddy Waters, Jackie Wilson and Ruth McFadden.

Now owned by the Elks Lodge, the building was preserved as a local historic landmark in 2016. The marker, which was erected in 2019, is located on Jefferson Street, just 0.1 mile west of 26th Avenue North.

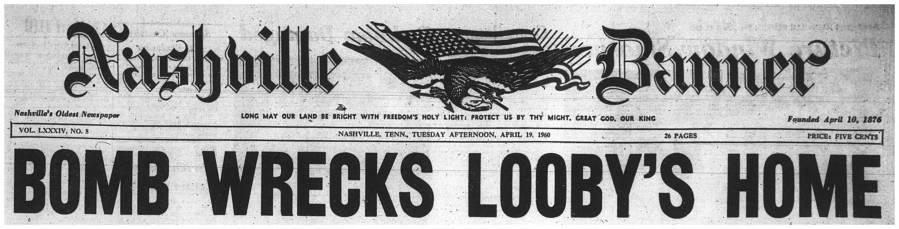

Bombing of the Z. Alexander Looby Home

This plaque marks the site of Z. Alexander Looby’s home, which was bombed on April 19, 1960, during a boycott of white-owned businesses to protest segregation in Nashville. Looby was a prominent civil rights lawyer from the late 1930s until the late 1960s.

He also served on the Nashville City Council and the Metropolitan Council. Looby and his wife, Grafta, survived the bombing, and in solidarity with the Looby family, around 3,000 civil rights activists marched on the Davidson County Courthouse later that day.

By June, the seven downtown Nashville stores originally targeted with sit-ins and other protests desegregated their lunch counters. Concern over the bombing of the Looby residence and the economic boycott helped achieve that result.

The historical marker can be found on Meharry Boulevard east of 21st Avenue North.

Tennessee Ornithological Society

This historical marker commemorates the founding of Tennessee’s oldest conservation group in continuing existence, the Tennessee Ornithological Society (TOS).

100 Oaks: The evolution of one of Nashville’s oldest malls

Dr. George Curtis, Albert F. Ganier, Judge H.Y. Hughes, Dr. George R. Mayfield, Dixon Merritt, and A.C. Webb founded the conservation group on Oct. 7, 1915, during a meeting at Faucon’s Restaurant at 419 Union Street, just 50 feet east of the marker.

The TOS was chartered by the state for the purpose of studying Tennessee birds. A journal, The Migrant, publishes accurate records of birds across the state. The Birds of the Nashville Area has local records.

Tennessee Hospital for the Insane

In 1832, the Tennessee legislature approved the state’s first asylum, which was established in 1840 southwest of Nashville. The state bought the land in 1848 after activist-reformer Dorothea Dix and asylum staff called for improved facilities.

Music City: How Nashville got its famous nickname

Prominent architect Adolphus Heiman designed the Gothic-style complex with octagonal towers and separate wards. The asylum opened in 1852 and was renamed Central State Hospital in 1920, before it closed in 1995.

Today, a stone gatehouse and unmarked graves are all that remain. The site is at the intersection of Murfreesboro Pike and Dell Parkway.

Nashville Sit-Ins

On Feb. 13, 1960, 124 students from Nashville’s Historically Black Colleges and Universities walked into Woolworth’s, Kress, and McClellan’s, sat down at the lunch counters and asked to be served to no avail.

The students also targeted Walgreens, W.T. Grant, as well as Harvey’s and Cain-Sloan department stores. Their goal was to desegregate Nashville lunch counters. The student protestors experienced no violence until Feb. 27.

On that day at Woolworth’s and McClellan’s, white resisters threw the students from their seats, punched, kicked and spat on them. Nashville police only arrested the student protestors. In total, 81 students were arrested and charged with loitering and disorderly conduct.

Batman Building: Meet the architects behind the design

Two days later, the court fined each student $50. They took a principled stand, refused to pay the bail and spent a little over 33 days in jail. On May 10, 1960, Nashville became the first major city to begin desegregating its public facilities when six downtown stores opened their lunch counters.

The Nashville Student Protest Movement to desegregate all public facilities did not end until 1964. The historical marker was placed north of Church Street on Rep. John Lewis Way North, near the Woolworth Theatre.

Maxwell House Hotel

This plaque marks the site of the Maxwell House Hotel, which was built by John Overton in 1859. After wartime use as a barracks, hospital and prison, it was formally opened as a hotel in 1869.

Middle Tennessee city is home to the ‘World’s Largest Cedar Bucket’

Presidents Andrew Johnson, Rutherford Hayes, Grover Cleveland, Theodore Roosevelt, William McKinley, William Howard Taft, and Woodrow Wilson lodged at the hotel, as did a host of celebrities from the world of business, politics, the arts and military services.

The hotel was eventually destroyed by a fire on Christmas Day in 1961. The historical marker can be found on the corner of the SunTrust Building on Church Street, just 0.1 mile west of 4th Avenue North.

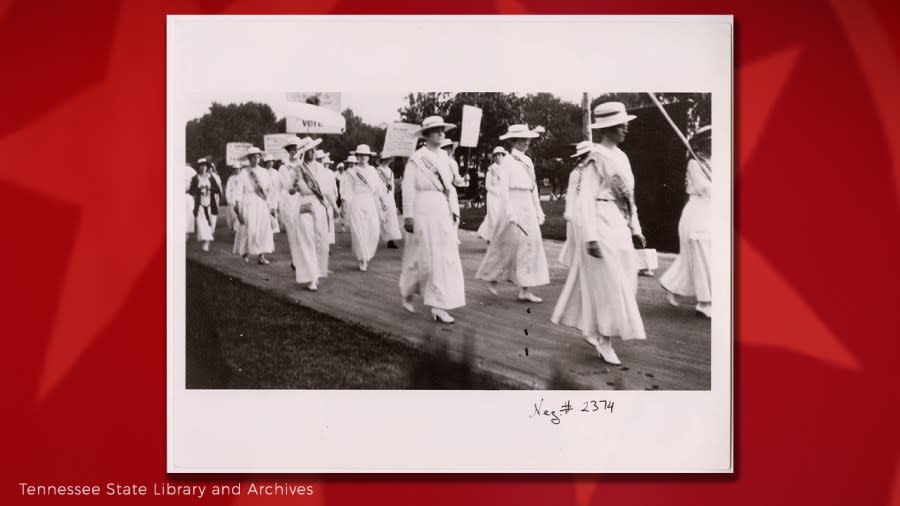

Campaign for the Vote

The Nashville Equal Suffrage League was formed near where this marker sits in 1911 at the former Tulane Hotel. In coordination with the Tennessee Equal Suffrage Association, the energetic efforts of women leaders influenced public opinion in the decade ahead.

Nashville’s suffragists hosted the 1914 convention of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), a milestone event. The Hermitage Hotel was the headquarters and became the site of many future suffrage activities.

The historical marker, which was erected in 2020, can be found on the grounds of Church Street Park at the intersection of Church Street and Anne Dallas Dudley Boulevard.

Among the leaders of the 19th Amendment victory in 1920 was Anne Dallas Dudley, for whom the boulevard in downtown Nashville is named. The Suffrage automobile parade of May 1915 formed up along the boulevard, and several war bond rallies were also held in the area.

Jack Clement Recording Studios

After success in Memphis with Sun Records, “Cowboy” Jack Clement founded Jack Clement Recording Studios in 1969, producing and writing for artists such as Johnny Cash and Charley Pride.

Patsy Cline’s memory lives on near crash site in Camden

It was the first facility of its kind in Nashville, with interiors designed by Jim Tilton. The studio was sold in 1979 and renamed Sound Emporium. Artists such as Kenny Rogers, Dottie West, Ray Stevens, Don Williams, John Denver, R.E.M., Robert Plant and Alison Krauss recorded there.

The historical marker, which was erected in 2013, is located on Belmont Boulevard south of Clayton Avenue in front of the Sound Emporium Recording Studios.

The Rock Block

One of Nashville’s oldest streets, Elliston Place was a popular commercial corridor by 1930. Elliston Place Soda Shop opened in 1939, and in 1971, Owsley Manier and Brugh Reynolds opened the listening-room style music venue Exit/In, named for its main rear entrance.

In the early 1980s, the area became known as “The Rock Block,” with businesses like The End, TGI Fridays, Obie’s Pizza, The Gold Rush and Mosko’s shaping Elliston Place’s legacy as Nashville’s counterculture epicenter.

Retro Nashville | Ride the nostalgia wave through Music City’s history

The historical marker, which was erected in 2020, can be found on Elliston Place just north of Louise Avenue in Midtown.

To view a map of all the historical markers erected by the Metro Historical Commission of Nashville and Davidson County, click here.

For the latest news, weather, sports, and streaming video, head to WKRN News 2.