Beilue column: A special love story in four acts

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Her ankles.

That’s what 17-year-old Max Sherman noticed when he first cast eyes upon striking Gene Alice Weinbroer in 1953. The place was the Hutchinson County Jail in Borger.

It should be said neither called the place a temporary home. Sherman was among four high school boys who held a church service at the jail. When another quartet of boys were invited one Sunday to sing, they brought along Gene Alice, 15, and her fold-up field organ.

“Her chiseled ankles were a work of art,” Sherman recalled.

When Max could force his eyes away from Gene Alice’s skin above her loafers and under her long skirt, he noticed she was having some trouble folding up the organ at the end of the service. He quickly rode to the rescue.

“No, thank you,” she told him. “I can do it myself.”

It was an inauspicious beginning, but a beginning nonetheless that now, with their 61st wedding anniversary at the end of July, is a relationship that has spanned nearly 70 years.

It is poignantly chronicled in Sherman’s memoir, “Releasing the Butterfly,” a compelling and rich story of two active, intertwined lives that are now in the long shadows of sweet twilight with Gene Alice’s advanced Alzheimer’s disease.

“Writing about Genie has been painful, joyful and healing,” he said.

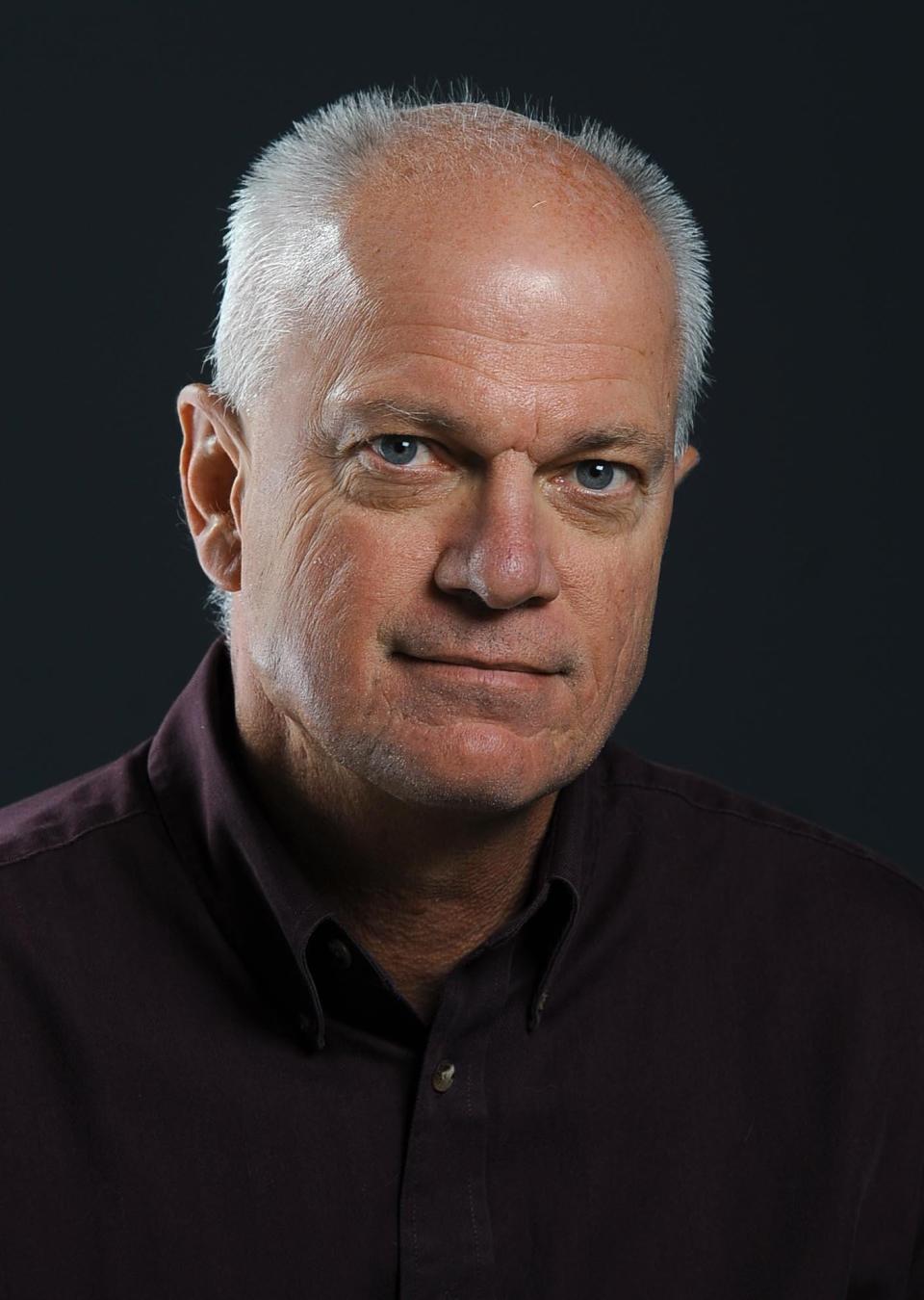

For many in the Texas Panhandle, the name of Max Sherman rings a long-ago bell. Sherman grew up in the small oil town of Phillips near Borger, idyllic in the 1950s and gone by 1987.

He was an attorney in Amarillo, a Texas state senator from the Panhandle from 1971 to 1977, president of then-West Texas State University from 1977 to 1982, and dean of the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas from 1983 to 1997.

For much of the last 20 years, the last eight years especially, Sherman has been a writer, a caregiver and a spouse coming to terms with a disease that slowly stole the beautiful mind of his accomplished wife, who resides in a memory care facility.

“I don’t have any real insight on how others need to come to terms with dementia or Alzheimer’s diagnosis,” Sherman said, “but I gained insight into my own struggle to not only survive, but be happy.

“My memoir was an attempt to pay tribute to my greatest love and to tell our story. Gene Alice and I virtually grew up together.”

Alzheimer’s, as Sherman’s memoir validates, is indiscriminate and silent. The brain disease that erodes memory and reasoning has 5.8 million Americans in its clutches. They can be rich or poor, large or small, slim or obese, uneducated, or like Gene Alice, a highly educated teacher, musician and culturally refined woman.

The monster was at the doorstep’

It was in December 2002 that Gene Alice leaned into her husband, kissed his cheek and said, “Max, for the first time in my life, I feel overwhelmed. I think I need to see a doctor.”

And so it began. As Sherman wrote, “The monster was on the doorstep, and I hadn’t even noticed.”

At first, the disease was almost imperceptible, and the diagnosis was mild. But dementia is always at the door, knock-knock-knocking and not going away.

Thirteen years later, in 2015, Sherman found himself doing what he never dreamed—placing three chairs in front of the door of Westminster Manor, their senior living apartment in Austin, to prevent Gene Alice from getting up in the middle of the night to walk outside to see what only she saw. She had done that the previous night.

While in his stocking feet, Sherman slipped and fell on the slippery polished wood floor. When he landed, he shattered his left femur. Rehab was his own challenge, but rehab also meant opportunity.

While Sherman was in the hospital, their children, Lynn and Holly, moved their mother to an adjacent memory care facility. When Max returned to their apartment, it was stark and empty.

“It was like a ghost town. It was lonely. The love was not there,” he said. “I’d wake up at 3 a.m. and have something on my mind. I’d always been a bit of a writer. I’d go to the computer and write something down. It became therapy.”

The story initially took on the form of a play with the inspiration of Thornton Wilder’s “Our Town.” Max and Gene Alice loved the theater. It was a storytelling style with which Max was comfortable. Later, an editor, Mary Ann Roser, came on board. The play became a narrative memoir. The original title, “One Helluva Woman,” became something else.

By happenstance, they both found themselves at Baylor in the 1950s and began to see each other. One evening, Max told Gene Alice about a drama class under Dr. Paul Baker and how it could change her life as it did his. It was a class in creativity, and Max began to recite from memory his final project, “Dakota Brave.”

A young brave gazed at a beautiful butterfly fluttering about on the horizon at sunset. He captured the butterfly, and examined it in an imaginary bowl. He was troubled as the butterfly, once flying celestially, now drooped and struggled. The brave let the butterfly go, watching it again flying strongly and free.

Gene Alice loved the story, and asked for several copies. She told Max what she wanted most was her freedom, freedom to be all she could be. So the memoir became “Releasing the Butterfly,” with the subtitle “A Love Affair in Four Acts.”

Above all, a love story

Gene Alice became all she could be. She graduated with a bachelor’s degree in English from Baylor. In their six sometimes-frustrating years of courtship, Gene Alice earned her master’s in English at the University of Wisconsin.

Through letters and occasional weekends together—Sherman was stationed at Fort Leonard Wood in Missouri—they hammered out the “Wisconsin Plan.” To alleviate Gene Alice’s future concerns, they would equally support each other to fulfill both of their dreams. She could be a wife, and also have her life.

After marrying in 1961, the Shermans spent 22 years in Amarillo. She taught English at Palo Duro High School, then joined the English faculty at Amarillo College and WT. She was at WT before Sherman became president.

Sherman thought his wife could have been president of AC during that time but the strain on the family would have been too great.

When Sherman left the Panhandle for the position at the University of Texas, Gene Alice became the director of the Thompson Conference Center at UT. This was in addition to playing as a church organist—a true love—and vast volunteer experiences in social services, the arts and humanities.

Gene Alice had always been an editor of her husband’s work, whether it was legal briefs or other important papers. In a way, it was no different with “Releasing the Butterfly.” On their visits, Max would read what he had written.

“She would nod or cut her eyes and smile at me,” he said. “I’m almost believing she’s heard every word.”

The memoir was finished in 2020. It has opened an invitation for others to talk to Sherman about their shared experiences with a loved one with Alzheimer’s.

It’s difficult to stop reading the 267 pages. It is not a woe-is-me account, but a frank and honest story of two who became one and seeing that there can still be small joys and triumphs in the twilight and freedom to still be.

In early August, Sherman’s memoir was reviewed in The Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, a peer-reviewed medical journal, by Jenny Sarpalius, wife of former state representative and U.S. congressman Bill Sarpalius.

“(‘Releasing the Butterfly’) is fundamentally one of the most beautifully written love stories ever told … a testament to Gene Alice’s strong will, independence and determination,” Sarpalius wrote. “What profoundly struck me was not only Gene Alice’s continued fierce determination at life, but Max’s unwavering love and commitment to Gene Alice that was no different from when he first laid eyes on her.”

These days, Max makes the short walk to see Gene Alice once in the morning and again in the afternoon. She is in a wheelchair now. He will talk. She will listen. Sometimes she takes his hand and won’t let him go. Sometimes Max will rest his head on her shoulder.

“I have learned to love in a different way and in a different place and in a different time,” he said.

Who knows. Like he did nearly 70 years ago, Max might even steal a glance at those ankles.

Editor's note: This column originally appeared on the WT website. Do you know of a student, faculty member, project, an alumnus or any other story idea for “WT: The Heart and Soul of the Texas Panhandle?” If so, email Jon Mark Beilue at jbeilue@wtamu.edu .

This article originally appeared on Amarillo Globe-News: Beilue: Former WT president’s memoir paints portrait of Alzheimer’s