Being Black in RI was tough in 1976. Exhibit portrays how much tougher to be Black and gay

Rodney Davis, who grew up in Newport and was a Jehovah's Witness, had two strikes against him from the outset, being Black and being gay. Those were the days when people like Davis gathered at Raffles, a gay bar that was the only refuge in the city. But they had to approach the place without being noticed.

That's the silence that kills, Davis says. It killed his two uncles, who died of HIV and AIDS. They were the two people in Davis's family who were like him. But in Davis's family, you didn't talk about being gay.

"That lack of wanting to tell these stories, to talk about these things, to engage with another, even in a way that is an argument, you just didn't do because it made it real," Davis said. "That’s why the closet is so deadly, because when we don't have these conversations and we don't see these things, if we can't see it, it is invisible."

When Davis came out, his world caved in. He was disfellowshipped from the Jehovah's Witnesses – akin to being excommunicated – a rejection that meant his community, including friends and family, would ignore him.

Billy Rose, a fellow native of Newport, was among those to whom Davis first came out. He, too, was Black, gay and grew up in a family of Jehovah's Witnesses. He understood implicitly.

"[He] gave me this sort of sagely advice about how I find my truth," Davis recalled. "That it's your truth. No one else’s."

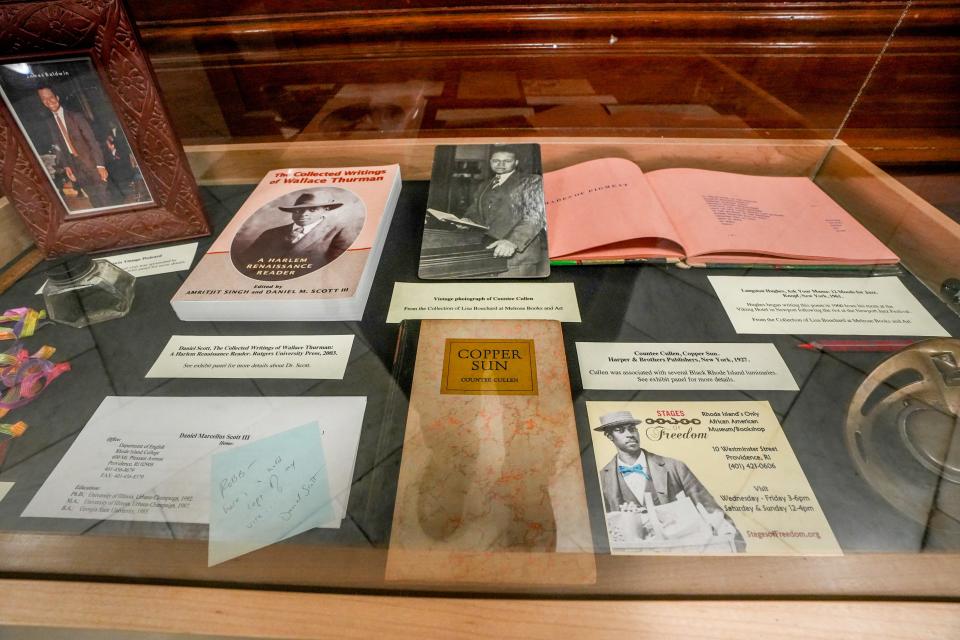

Rose and Davis are among those represented in Stages of Freedom's latest exhibit, "Black Lavender," on display in Providence City Hall. Robb Dimmick, who cofounded the museum and bookstore with local civil-rights advocate Ray Rickman, developed the third-floor exhibit with a trove of research, and support from the Rhode Island Foundation's Equity Action Fund.

Dimmick emphasized that Rhode Island's Black history – on which Stages of Freedom is focused – is only beginning to be understood.

"The depth of that story, the richness of that story, the pain of that story, we're just starting to tell it," Dimmick said. "And so when you talk about being Black and gay, you have this this double whammy of invisibility and the fear of being visible in it, and particularly not just the Jehovah Witnesses, but the Catholicism of Rhode Island, which permeated everything" in a thoroughly interconnected population.

State's first Pride parade sparked legal battle

The Providence Journal earned a small place in Dimmick's exhibit due to its coverage of Rhode Island's first gay pride parade in 1976, several years after the first gay pride marches in New York and Chicago.

That year, a headline ran that read: "City tolerates first homosexual parade."

About 70 people marched, and it took a court order to guarantee that they could. It was the same year Rhode Island celebrated its bicentennial, and the state's Bicentennial Commission and police rejected the parade, contending that being gay wasn't related to the state's history, and arguing that because being gay was outlawed at the time, the parade could not be allowed.

A judge determined that the parade was a matter of free speech under the First Amendment and decided the event must move forward and must be protected.

Yet not all marched. The Journal's article quotes an unnamed Warwick man who lamented his absence from the parade.

"I know hundreds who want to be in there but are afraid because they have good jobs," the man said.

Living as Black and gay: 'An extraordinary leap of faith'

Fear of being found out was very real, especially in an insular place like Rhode Island.

"You knew that if you did something, everybody was going to know about it," Dimmick said, "because of the ... claustrophobia of our small state, [which] means that being brave to go into a Raffles is an extraordinary leap of faith and courage."

Dimmick wants to ensure those acts of courage aren't forgotten.

Black Lavender is open for free on the third floor of Providence City Hall through the end of July.

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Black, gay life in RI is focus of new exhibit in Providence City Hall