Being the first Black female military pilots wasn’t easy. Now they help others fly

The first Black female pilots in the Army and Navy made history just months apart. But a year later, one would have her flight status taken away, and the other would be left questioning how close she came to also losing her military flying career.

Until now, neither Army Lt. Col. Marcella Hayes Ng, the nation’s first Black female military pilot, nor Lt. Cmdr. Brenda Robinson, the Navy’s first Black female pilot, has shared publicly the details of the difficulties they faced as “firsts.”

Both are now retired, and spoke to McClatchy about ideas on what can be done to get more minority women to fly as the Pentagon conducts a review on diversity in the military.

“That’s the challenge, to keep telling young people, and especially young ladies, don’t let the circumstances of where you are, regardless of how rough it was, regardless of how bad it was, define who you are. Because that’s not who you are,” Ng said.

The military has been tackling discrimination within its ranks and leadership for years. There is a more intensified Pentagon-wide effort underway now, following the nationwide protests over the death of George Floyd in police custody.

Army officers interviewed by McClatchy said the service will soon be releasing an extensive plan for leadership to address racial and gender bias, which could help prevent what happened to Ng from happening to future minority women who pursue aviation slots.

“If you want to be an aviator, don’t allow what has happened in the past to make you think you can’t,” said Col. Timothy Holman, chief diversity officer for the Army. “Because there are firsts that happen every day.”

Forty years ago, Ng was that first.

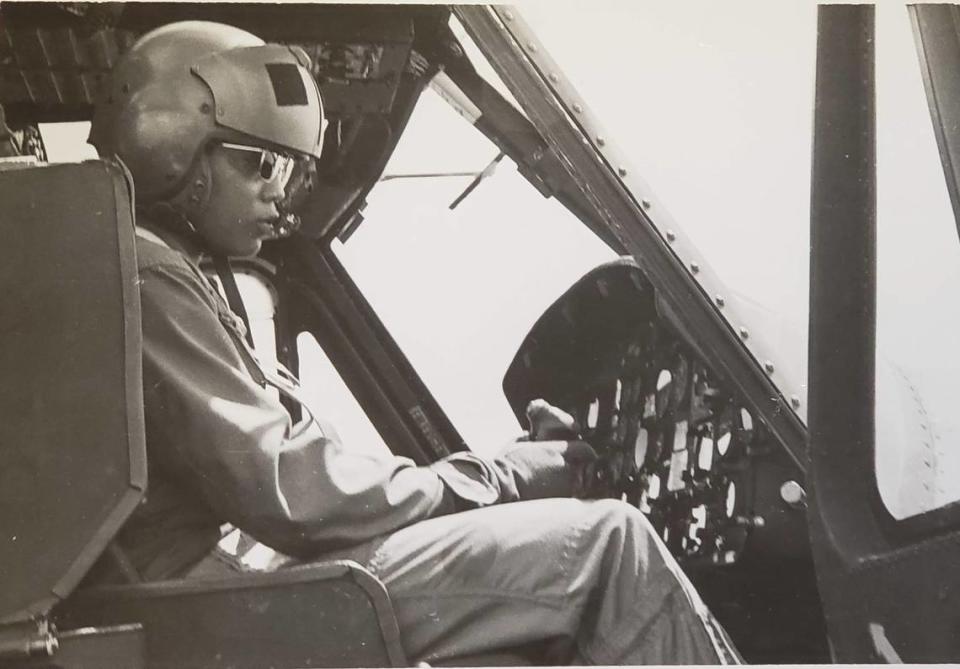

The Army had only opened flying roles to women five years earlier. After Ng completed Airborne School and jumped from aircraft at Fort Benning in Georgia, her commander encouraged her to take the Army’s flight aptitude test. When Ng graduated flight school in 1979 at Alabama’s Fort Rucker, she was the Army’s 55th female pilot overall.

Ng deployed overseas, assigned to the 394th Transportation Battalion in Nellingen, Germany. But she could immediately tell some of the officers were not welcoming.

“There were some serious challenges, because I was a two-fer,” she said. “I was the first Black, and I was the first woman.”

She needed their support. To fly the Army’s UH-1 “Huey” helicopters overseas, the battalion had to test and clear her for in-country flying. But her commanders did not approve flight time, and when she did fly, she did not get needed feedback.

“At this point, I couldn’t even tell you the story without bursting into tears,” Ng said. “I would go for weeks, close to a month before I would get in the aircraft again. So, you know, you get to the point where you’re getting rusty.”

Contrary to procedure, she was handed her evaluations all at once, several flights later, when it was too late to make constructive changes.

“You’re thinking that you did pretty decent that one day, and now they’re all negative,” Ng said of her performance write-ups.

At that point, a second female helicopter pilot who had also been at Fort Rucker, now retired Brig. Gen. Maureen LeBoeuf, was sent to the battalion in Germany.

At Fort Rucker, Ng’s instructors “had all commented on her great skills as a pilot,” LeBoeuf later recalled in a book she wrote on leadership. But at the 394th, “each time she [Ng] went out, she was failed.”

Ng got rattled. On her final test, she failed.

She appealed the decision to a flight evaluation board but didn’t know how to convince them to reinstate her.

“I didn’t understand enough about the Army, or the world at the time, to know that I didn’t really need to prove that I’d been discriminated [against],” Ng said. “They needed to prove that they had not.”

In her book, LeBoeuf lamented how Ng was treated. LeBoeuf declined to be interviewed for this article.

“For me, this was a fundamental failure of leadership and a lack of care and concern for another officer, another soldier, and fellow Army aviator,” LeBoeuf wrote in “Developing your Philosophy in Living and Leading,” which was published in 2019.

In sharing her story, Ng emphasized that there were only a few officers in the 394th who negatively impacted her career. When a change of command occurred in the unit, she not only found support, but also mentors who cultivated her for future command responsibilities.

Ng chose to continue serving. The loss of her flight status, however, still stung.

“But why?” Ng recalled telling LeBoeuf at the time. “Just because I dared to fly? This is crazy.”

In interviews with McClatchy, Ng and other Black female pilots who led in breaking barriers in the military said if the Pentagon is serious about making the military more inclusive, one area to look at is how the services determine who is qualified to fly.

For decades, becoming an aviator has marked a path for future military leadership. A 2002 Defense Department study found that in the Air Force alone, over one-half of the general officers during the previous 20 years had been pilots.

But that path has been more difficult for minorities. A separate 2017 RAND study commissioned by the Air Force found that 19 percent of Black pilots failed — or washed out — of the service during initial flight training compared to 7.5 percent of their white counterparts.

After nationwide protests on racial disparities, Defense Secretary Mark Esper in July ordered a review of what policies may be contributing to a lack of diversity in military leadership, particularly in its highest ranks. Of the Pentagon’s 921 one-star to four-star generals, 808 are white, 75 are Black, 16 are Asian, two are Pacific Islander and the remaining 20 were either identified as unknown or multiple races, according to the Defense Department’s fiscal year 2020 manpower report. Of the 69 female generals serving, only one is a four-star.

THE NAVY’S FIRST

In 2016, Women in Aviation International inducted Robinson into their hall of fame for her role as the Navy’s first female Black pilot and her aviation career that followed. At the ceremony, she was surrounded by women dressed in flight suits.

“I love seeing women, all women, in flight suits,” Robinson said. But something was amiss.

“They were all standing around, talking confidently. I’m looking at these ladies, and I go, ‘What happened to the Black ladies?’”

In the decades since Ng became the first, the number of Black female military pilots has not significantly grown. As of July, there were just 72 Black females among the 44,000 total pilots across all services, according to military data obtained by McClatchy.

At the hall of fame ceremony, Robinson said pilots told her they had known of Black female students, but they had not made it through the training.

Robinson could relate. She too almost washed out.

“It’s very easy to wash out and nobody even knows that you are there,” Robinson said.

Robinson had earned her pilot’s license and an aeronautical degree from Dowling College in New York before she joined the Navy. That background helped her complete the Navy’s basic flight training in Pensacola, Florida, with scores high enough to qualify for jets when she entered the Navy’s advanced flight school in Corpus Christi, Texas, in 1980.

She had almost made it through the course without a flying error, or “down,” on her record, then she made one.

Robinson was mortified. She knew three mistakes could get her washed out.

Robinson says her instructor afterward told her something that rattled her more: “You know you can’t get any more downs or you are going to be out of the program.”

She previously had a clean record, so she was puzzled, because if there had been a previous down, “I would have gone before a board, I would have known,” Robinson said.

TOLD TO ‘DROP IT’

In hindsight, she thinks another pilot’s flight mistake was placed in her record. But at the time she didn’t challenge it.

“I was told to ‘drop it’ or I was not going to go on,” Robinson said. “So I dropped it. I was scared to death. I thought they were going to get rid of me at any minute.”

Robinson did what she now coaches younger pilots to do: Find mentors early, and go to them for help. Robinson sought help from a newly minted Navy female flight instructor, the now retired Navy Rear Adm. Wendi Carpenter.

Carpenter, who was the Navy’s first female aviator to make admiral, had just gone through flight training in Pensacola and Corpus Christi too. She knew that while most of the instructors were fair-minded, there were still a few she had encountered who did not think women should be flying.

“The fact that Brenda was the first Black woman aviator going through was a big deal, you know, and that was the extra pressure. And I’m sure that there were guys all along the way that thought, ‘Well, women shouldn’t be flying and especially not a Black woman’ because we didn’t have a lot of Black aviators anyway.”

Carpenter had been asked to stay at Corpus Christi after graduation because the Navy saw she could be a skilled teacher, and she became a go-to adviser when students were struggling.

When she mentored Robinson, “I remember she was afraid,” Carpenter said, noting that most flight students feared washing out.

Robinson said Carpenter helped her work through each flight so she would succeed.

Robinson passed, earned her Wings of Gold and the call sign “Raven.” She began flying Grumman C1-A Traders to resupply the aircraft carrier USS America. Over her Navy career she completed 115 carrier landings and went on to become one of the first Black female pilots for American Airlines.

“You cannot go through flight school alone,” Robinson said. “You can’t go through civilian flight school alone and you definitely cannot go through military flight school alone.”

Like Ng, Robinson does not focus on the past, and does not share the story of almost washing out with the children she now coaches at her aviation camp in Charlotte, N.C.

“That never helped me, and it certainly wasn’t going to help kids. I never want to say to them, well these are the kind of terrible things that happened to me and you can overcome it by doing this. No. Kids have their own set of problems right now. The world is way different,” she said.

However, in the context of the deeper inclusivity reviews the military is doing now, it could be valuable to take a look back, she said.

“This is a time that people want to explore what happened. How come things are not going right?” Robinson said. “You have to give folks a safe place to actually say what’s going on.”

The Navy is presently trying to do just that, through “listening sessions” on racism and sexism and a more structured outreach to 500 focus groups across the service, said spokesman Cmdr. David Hecht.

“At this point, the primary focus has been on actively listening to our sailors from all over the world through a variety of methods,” Hecht said.

In her camps, Robinson focuses on building the next generation of pilots by encouraging children, who often come from underrepresented or lower income backgrounds, to see that a career in aviation is within their reach.

“A lot of young people will look and believe that ‘this is not a job for me because I’m probably not smart enough for that,’” Robinson said. ”They don’t realize that they have everything they need to be a success. They just don’t see that yet. So it’s my job to point that out to them.”

Robinson said she also coaches them on how to push past people who doubt them.

“There’s always a brick wall.” Robinson said. “We all have to make a decision. Are we going to fight our way through it, or are we going to cut and run? Cut and run doesn’t work. So put on your confident face, you know, and I teach them how to do that, and blast right through it.”

FULL CIRCLE

Ng was commanding the 49th Transportation Battalion at Fort Hood, Texas, in 1999 when a young Black female Army captain, another helicopter pilot, approached her for help.

“She was going through the exact same thing I’d done, just 20 years later,” Ng said. “For me personally, God was saying, Marcy, for such a time as this, you need to tell her how to fight this battle. For you didn’t know how to fight it. You were still green around the gills. Tell her how to fight it. So I was able to equip her with the tools for what she needed to do.”

In 2019, a member of the Organization of Black Aerospace Professionals wanted to induct Ng into the group’s hall of fame. She hesitated. She felt she hadn’t really had a flying career. But she was persuaded: “First is first.”

Ng accepted, and in her speech to the organization, reflected on her role.

“If I took a bunch of the hard knocks, did it cause someone else to not have to go through those? Then it wasn’t wasted. It wasn’t wasted at all.”