Benefit shortfalls can cost seniors their homes, and NJ shelters can't meet medical needs

Feeling stunned and overwhelmed, Raymond Decker grabbed his green-eyed tabby cat Tabitha as a court officer marched into his Montville home and swiftly loaded a U-Haul with Decker’s belongings and furniture.

Decker’s monthly Social Security check of $906 had not been enough to cover his $1,250 rent. He had moved to Montville after selling his deceased mother’s white clapboard house in Butler, where he had lived for 15 years while caring for her until she died. He had pieced together rent payments for close to two years, but once the funds from the home's sale were depleted, he started missing payments, and he was evicted last May.

The 64-year-old stayed with a friend, accepted help from the Salvation Army and nourish.NJ, a soup kitchen and homelessness nonprofit, and paid out of pocket for a month in a motel room he described as filthy and cockroach-infested.

He found Tabitha a foster home, and made sure he was extra careful about his blood sugar levels and eating right before bedtime.

Decker is among the growing number of New Jerseyans older than 55 who experience homelessness, a trend that strains an already swamped shelter system not designed for people with serious health care needs, and which illuminates the region's deficit of available affordable senior housing.

As part of its ongoing series “Aging in New Jersey,” NorthJersey.com and the USA Today Network New Jersey today examine the unique medical challenges and other hurdles faced by older residents who find themselves homeless.

While 55 is usually too young for someone to be considered a “senior” or “elderly,” homelessness throws a wrench into the mix. People who experience homelessness are more likely than people with stable housing to develop chronic medical conditions, because being homeless comes with stress, unsafe environments, a lack of access to medicine or healthy foods, exposure to the elements and more.

'I can't stay here forever'

Raymond Decker had suffered from diabetes since he was a child but discovered an astonishing safeguard six years ago, when his cat, Tabitha, started to sleep on Decker’s chest. If she sensed that his blood sugar levels were dropping too low — his doctor said she felt a change in his body temperature — she would wake Decker up, knead his chest and lick his face.

Now that he was homeless and no longer had Tabitha, he had trouble sleeping. He missed her — and her lifesaving wake-up face licks.

“It was very rough — she’s the only family I really have,” Decker said recently.

After about two months of uncertainty, he moved off the waitlist into a bed at Homeless Solutions, the largest homeless shelter in Morris County. A few months into his stay, a semi-private room with a door became available, and with a doctor’s note and service animal registration, Tabitha and Decker were reunited.

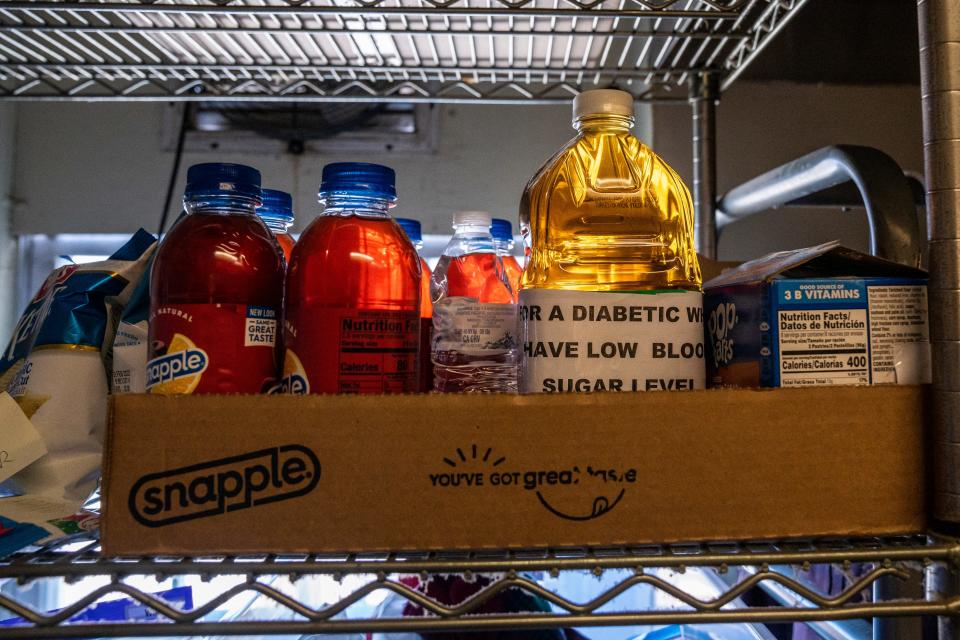

Decker does what he can to contribute to shelter chores, like cleaning tables after dinner, but he has a shoulder injury, and pain shoots down his legs to his feet from the nerve damage brought on by his diabetes. He buys his own diabetic-friendly food with his food stamps — which inevitably run out before the month is up — and shelter volunteers prepare his whole wheat pasta, brown rice and salads, in addition to the three meals a day they serve to the 84 other shelter residents.

“I wasn’t sure what it was going to be like, but it’s very good here,” Decker said of Homeless Solutions. “But I can’t stay here forever.”

Homeless people experience more chronic illness, stress

Being homeless can cause and quickly exacerbate health conditions that housed people are less likely to experience. For instance, relatively young unhoused adults often struggle with “geriatric conditions” such as memory loss, falls and bladder issues that adults in stable homes won't face until they are 15 to 20 years older, studies have found.

“Similarly, we see behavioral health conditions like depression and anxiety understandably get much worse when you're homeless,” said Barbara DiPietro, senior director of policy at the National Health Care for the Homeless Council.

"The experience of homelessness itself is so traumatic that it either creates new health conditions or it exacerbates the health conditions that were already there."

Barbara DiPietro, senior director of policy at the National Health Care for the Homeless Council

“Not only can any of these conditions cause homelessness, but the experience of homelessness itself is so traumatic that it either creates new health conditions or it exacerbates the health conditions that were already there, like diabetes,” she said.

In 2018, shelters across New Jersey served 2,490 people who were 55 and older, according to data from the state Homeless Management Information System. That number grew to 2,716 in 2022.

Aging in NJ series:What happens when an elderly relative can’t live alone? What to know about aging in NJ

Homelessness:Code Blue helps NJ homeless when temps drop, but some still get left out in the cold

Each year, volunteers attempt to count the homeless population staying in shelters as well as sleeping on the streets and in other places not meant for human habitation. The ultimate tally is inevitably an undercount.

But the surveys showed that people 55 and older made up 12% of New Jersey's homeless population in 2014. Eight years later, that jumped to 22%, according to reporting from Monarch Housing Associates.

In 2014, 144 New Jerseyans older than 65 were sleeping in shelters across the state on one night in January. In 2022, there were 298.

Providers cite different reasons for the increase. In Bergen County’s only shelter, staff members are seeing seniors experience housing instability for the first time, grapple with health issues, experience the death of a partner or parent, face rising housing costs, or suffer foreclosure after a reverse mortgage. Others lost or left their jobs when COVID-19 struck, and some are suffering the effects of long-haul COVID.

Over the past three years at Homeless Solutions, about half of the seniors living in its facilities were chronically homeless, meaning they had a disability and didn’t have a stable place to live for at least a year. In recent years, a majority of seniors at the Morristown shelter have wrestled with mental health conditions and substance abuse disorders.

There’s also a “cohort” theory that the generation of post-World War II baby boomers born between 1955 and 1965 has faced historically difficult economic and social pressures, including high home prices, lower wages and recurring recessions. Because of these difficult circumstances, that generation has consistently made up the biggest share of the homeless population in the past few decades, according to Dennis Culhane, a homelessness researcher at the University of Pennsylvania.

Culhane predicts that the homeless population 65 and older will nearly triple over the next decade.

A never-ending cycle

There is no single answer to solve elder homelessness. But one of the major solutions — desperately needed affordable housing — often faces onerous roadblocks.

Decker searches listings and patiently waits to hear back on his applications for affordable senior housing. The 85-bed Morristown shelter has been his home for nine months.

His search has not been easy. His first choice, Butler Senior Community — less than a mile from his old house, where he has a network of friends such as his former colleagues at the police department — rejected him after he languished on its waitlist for close to five years. He had an eviction on his record and bad credit, they said.

He tried to appeal, to no avail.

Story continues below photo gallery.

“That’s where I would really like to be, but they won’t talk to me about it,” Decker said. “I would be paying 30% of my gross income. That would be no problem.”

Julia Zauner, vice president of marketing and communications for Springpoint, which owns Butler Senior Community, said the company tries “to be very forgiving” in the scoring process and doesn’t dock applicants for medical debt.

“The process is equitable for all applicants, and we do have that criteria just to make sure that we are going to have successful tenants,” Zauner said. “We really don't want to deny anyone, because we are in the business of providing housing for people, but we want to make sure that we have successful tenants. That way, we have a safe, comfortable and stable environment for all of our residents.”

Aging:When it's time to stop driving, how can seniors get around car-centric New Jersey?

Homeless hurdles:It's tough for NJ's homeless to get IDs. But to access vital services, they must show IDs

Butler Senior Community is funded with low-income housing tax credits, a federal subsidy that supports the construction of affordable housing. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development allows owners to reject an applicant for poor credit history, but not a lack of credit history, said spokesperson Olga Alvarez.

During each legislative session over the past decade, New Jersey lawmakers have introduced a bill that would force landlords to consider alternative ways to judge creditworthiness for those seeking subsidized housing, such as employment and health history or extenuating circumstances that caused a renter to miss a past payment. It is currently stalled in committee.

"The way to emerge from homelessness is to secure affordable housing, but if you can’t get the affordable housing, then you’re just in this never-ending cycle,” said Shannon Muti, director of programs and services at Homeless Solutions.

Harder to assist older shelter residents

The graying homeless population is also straining overburdened shelter providers, which are often not equipped to deal with older residents’ specialized needs.

“We by and large as an industry cannot do a good job with folks who are deaf, with folks who are blind or in wheelchairs, with special needs, because the system is stretched so thin that just meeting the basic needs is so overwhelming,” said Connie Mercer, CEO of the New Jersey Coalition to End Homelessness.

Homeless Solutions employees in Morristown try to place seniors in beds close to the bathrooms, but the distance can still be too far for older people who have difficulty walking.

“We see a lot of accidents, so we do try to keep adult diapers handy,” Muti said.

The shelter dismantled its bunk beds to ensure there is at least 6 feet of space separating residents — but the change also provided a relief for the seniors who couldn’t climb in and out of the bunks each day.

Shelters describe an array of other issues that make it harder to assist older homeless clients.

The nonprofit shelter The Rescue Mission of Trenton provides lockers for clients to store personal belongings, but people have stolen medication, and it can be difficult to get a refill for those who need it, said Tyree Adams, director of emergency services.

Because of physical disabilities, it’s harder for older people to complete required chores in a shelter, which can cause resentment among younger residents, said Richard Williams, executive director of St. Paul’s Community Development Corporation in Paterson.

Unreliable medical transit

Getting to medical appointments poses yet another challenge for seniors staying in shelters.

The state-contracted medical transportation company for Medicaid patients is unreliable, patients say. Decker has a weekly pain management appointment, and said he has waited for hours multiple times for drivers who never show up. Muti estimates the company cancels on shelter residents multiple times per week.

New Jersey pays Modivcare, a Colorado-based company formerly known as Logisticare, nearly $180 million a year to oversee the transport of the state’s more than 2 million low-income Medicaid recipients.

The New Jersey Department of Human Services fined Modivcare nearly $1.7 million between 2017 and 2022 for not meeting contract requirements, such as failing to make scheduled pickups.

“Our overarching mission is to improve access to care for those in need, and we understand that non-emergency medical transportation is a vital service for safe, reliable transportation,” said Melody Lai, senior manager at Modivcare. “We look forward to working with Homeless Solutions to learn more about their specific challenges and to develop a customized plan to serve their unique population.”

Few resources for older shelter residents

Usually, shelter residents leave facilities during the day to go to work or search for a new job. That’s not the case for people who are retired or disabled.

Bergen County’s shelter in Hackensack — where more than half of people staying one night in February were 51 and older — helps organize trips to adult day care. Homeless Solutions is inviting volunteer groups to teach knitting and crafts.

But it’s more than keeping seniors entertained.

Older shelter residents suffering from dementia "tend to need more staff intervention, redirecting, reminders, things like that, that tend to be more work,” said Julia Orlando, director of the Bergen County Housing, Health and Human Services Center. “They get lost sometimes. We can’t offer 24/7 supervision.”

Unfortunately, there are few alternatives.

“We need more types of places they can live,” Orlando said. “We don’t have senior shelters in New Jersey that would have different beds or comfy chairs or room for someone with a colostomy bag or who's on oxygen.”

What needs to be done

New Jerseyans of all ages struggle to afford a place to live.

The Garden State lacks more than 200,000 homes for extremely low-income renters, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition. New Jersey — like the nation — needs to build more homes across the board, advocates say.

Some housing hurdles are the same, regardless of age.

For instance, if a senior obtains one of the rare, coveted housing choice vouchers known as Section 8, they still face the challenge of finding a landlord who would accept the voucher, because the amount no longer realistically covers median rental rates, said Williams, in Paterson. Section 8 — the second-largest public housing assistance, behind tax credits — should be strengthened and fully funded, advocates say.

Other solutions can be tailored to seniors, say Justice in Aging, a group fighting senior poverty, and the National Alliance to End Homelessness:

Expand social safety net programs like Social Security and Supplemental Security Income so seniors can afford basic needs.

Increase funding to health care providers that offer preventive care to homeless seniors.

Offer more low-cost or free legal services to assist seniors at risk of eviction or foreclosure.

Create more senior “supportive” affordable housing that offers resources onsite such as counseling, mental health experts and medical professionals.

Overwhelmed but still vital

Despite their drawbacks, the region's overwhelmed shelters remain a lifesaving last resort for some older New Jerseyans.

Leonard Proctor, 68, wandered into the men’s emergency shelter tucked behind the nearly two-century-old, stone gothic-style St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Paterson during the frigid days of January.

“I have nowhere to go, and I can’t sleep outside another night,” Proctor told Natasha McCutchen, the shelter manager.

Proctor was on Social Security after retiring from a long career as a welder in Paterson. He had been living with his girlfriend when they were evicted. He began sleeping in abandoned houses until it became too cold.

Every few months he is overcome with excruciating pain that stops him in his tracks. He thinks it’s a result of his heart transplant.

Leaning against his cane, he slowly walked to his cot, one of 40 in a crowded but organized room with thick yellow columns that created a semblance of privacy between some of the beds. Shoes, plastic boxes, clothes and other belongings spilled out from under white linen sheets. Proctor pulled out a red-bound Bible.

“If it weren’t for Natasha — or God," he said, "I’d be dead.”

Coming next week: Most New Jerseyans want to live out their final years in the familiar surroundings of their own home. But the physical and financial hurdles can be staggering.

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: More NJ elderly are turning to homeless shelters when money runs low