‘I was beside myself.’ Victim's father still haunted by killer’s broken promise

Editor’s note: This article describes abusive dating relationships and the violent murder of a high school student. Call the National Teen Dating Abuse Helpline at 866-331-9474, text “LOVEIS” to 22522 or visit loveisrespect.org for immediate, confidential assistance.

The silence lasted a good five seconds, long enough for Drew Crecente to wonder if he had been the first person to ask the question.

“Can’t you require him to testify against his accomplice in order to get this 35 years?” Crecente asked, pacing across his sunroom in Atlanta while talking on the phone with prosecutors from the Travis County district attorney’s office.

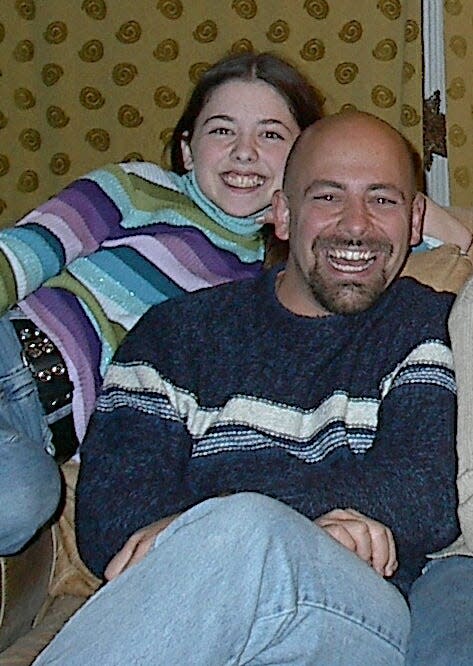

It was the summer of 2007, and prosecutors were hammering out a plea deal with Justin Crabbe for killing his ex-girlfriend, 18-year-old Jennifer Crecente, a year earlier. Crabbe lured Jennifer to a wooded area in Southwest Austin, near the home she shared with her mom, then shot the teen with a sawed-off shotgun.

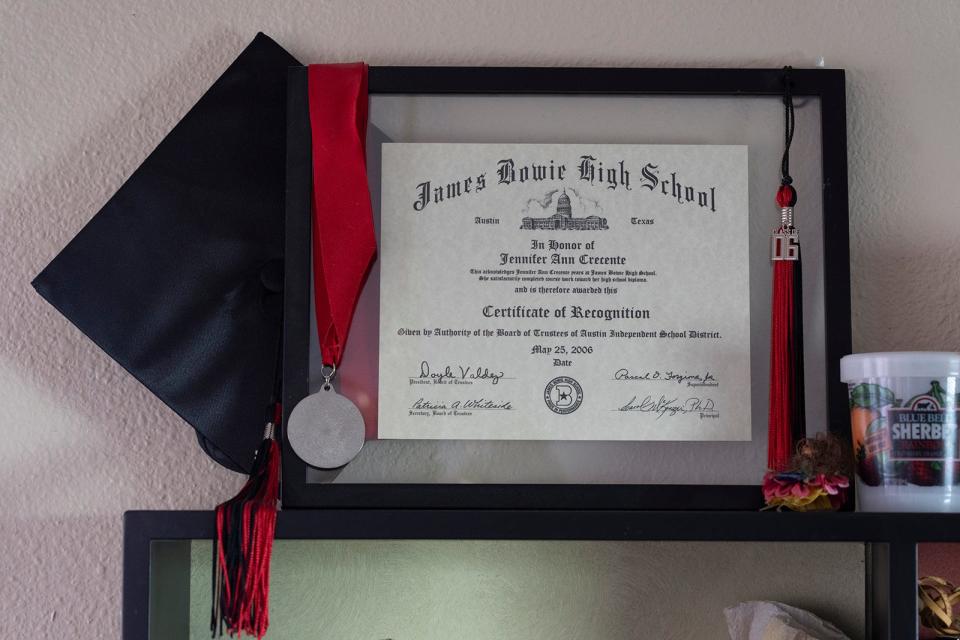

Jennifer died three months shy of her graduation from Bowie High School.

Drew Crecente didn’t think 35 years was enough for the young man who murdered his daughter. “But I knew at the time: I don't get to veto these things,” he told me. So he looked for ways to get more out of the deal.

He asked if they could require Crabbe to serve the full sentence, with no chance for parole? That was a nonstarter under Texas law.

Then Crecente asked how Crabbe, already a felon, got the shotgun. And why the person who sold it to Crabbe hadn’t been charged. And whether prosecutors could build a case if they required Crabbe to testify against that person as part of his plea deal.

After a lengthy pause, Crecente recalled, a supervisor at the DA’s office said, “Yeah, we can do that.” Prosecutors started talking about a grand jury that was meeting in the coming days, and how they could bring Crabbe to testify there.

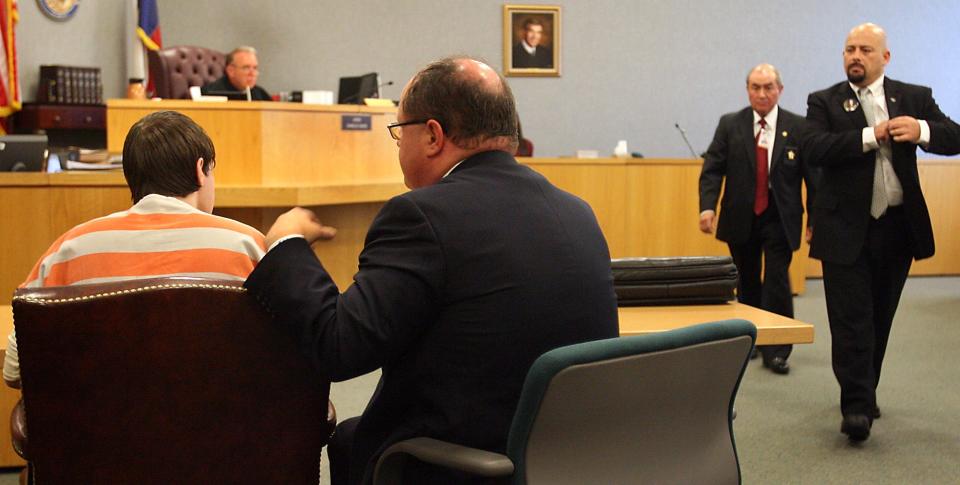

The plan was publicly revealed Aug. 1, 2007, as Crabbe took the 35-year plea in court and prosecutors announced the indictment and arrest of his alleged accomplice, Ricardo “Richard” Roman. Assistant District Attorney Amy Meredith told reporters that Crabbe would testify, if needed, against Roman.

Except when that time came months later, Crabbe refused.

Without Crabbe’s cooperation, the case against Roman fell apart. Prosecutors dropped the charges on Feb. 15, 2008 — the second anniversary of Jennifer’s death.

The jagged edges of that broken promise left a wound that is still raw for Jennifer’s family.

Now the matter has fresh relevance: Crabbe, now 35, is coming up this month for his first parole review. Drew Crecente is making sure the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles knows exactly what happened the last time the state of Texas counted on Crabbe’s word.

“He has already benefited from a lenient sentence which he did not earn,” Crecente said. “It is galling if he now expects the state to reward him further.”

Two men, two different stories

Roman is now 40 and lives in Rockport, where he moved after Jennifer’s murder. He did not respond to my questions about this case.

But Austin police records show he was on investigators’ radar from the beginning.

Four hours before Jennifer was killed, surveillance cameras at Academy Sports & Outdoors captured images of Crabbe and Roman shopping for shotgun shells. Police records say Roman’s fingerprints were found on the box of ammunition left near the crime scene, stashed in a green duffel bag that Roman gave Crabbe that afternoon.

Also found in that duffel bag: the shotgun used in the murder. In a sworn statement to police, a witness said Roman bragged about buying the shotgun for $200 and selling it to Crabbe for $1,000.

But from the outset, Crabbe, then 18, and Roman, then 22, told starkly different stories.

Crabbe told police in a sworn statement that he bought the gun from Roman, and that the two of them were playing with it in the woods when it accidentally went off, killing Jennifer.

Roman repeatedly denied knowing Crabbe until detectives told him about the security camera footage from the sporting goods store, according to police reports. Then Roman told police that Crabbe bought the gun from a stranger, claiming he needed it for a drug deal, and Roman helped him pick out the ammunition.

"I told him if he was dealing with people who had 20 lbs of Heroin, he was dealing with a bunch of people and would want the BB (shotgun shells),” Roman said in his official statement to Austin police in 2006. Neither one of them had an ID, Roman said, so they gave Crabbe’s money to a friend to buy the ammunition.

Roman insisted he was nowhere near the woods when Jennifer was shot.

Police promptly arrested Crabbe for the Feb. 15, 2006, murder. But Jennifer’s family was baffled that no charges were filed against Roman. Crabbe’s previous efforts to get a gun, including by breaking into his mother’s safe, were unsuccessful. Evidence linked Roman to the weapon that made the murder possible.

Under Texas law, a person can be guilty of murder if they “aid or attempt to aid the other person to commit the offense.”

As late as June 29, 2007, an email between staffers at the DA’s office said they “could not press charges at this time against” Roman because they needed “corroborating evidence beyond defendants testifying against one another.”

Then things quickly changed.

On July 13, 2007, prosecutor Amy Meredith emailed colleagues that “I just got off the phone with Drew (Crecente) … and gave him an update that we will be going to the Grand Jury on Tuesday.”

On July 17, 2007, the grand jury indicted Roman for murder.

On Aug. 1, 2007, prosecutors publicly announced Roman’s indictment and arrest as Crabbe entered his guilty plea. “We believe (Crabbe) is going to be testifying truthfully and cooperating with the state at a later trial,” Meredith told reporters then.

But that part wasn’t written into the official plea.

A perplexing plea deal

Drew Crecente delivered his words like a curse, staring at Crabbe with icy intensity.

“No matter what else you ever do with your life,” Crecente said at the 2007 sentencing, “you will forever be the coward that shot my daughter from behind.”

Crabbe kept his head down, showing no emotion.

“He did not appear to be somebody who was broken down by the gravity of what he had done,” Crecente told me recently.

Still, Crecente wasn’t prepared for the gut punch that came six months later. The DA’s office told him it had to drop the charge against Roman because Crabbe was refusing to testify, and there wasn’t much of a case without him. In the court docket, the explanation for the dropped charge simply said, "Witness refusing to testify."

“I was beside myself. I was incredibly upset,” Crecente said. “I still, to this day, don’t understand why there was nothing (that prosecutors) could do about it.”

In 2008, the head of the DA's trial division at the time, Buddy Meyer, told the American-Statesman that the 35-year plea deal had been reached with Crabbe before he offered his testimony against Roman, so one was never tied to the other.

But Jennifer’s family members say that’s not what they were told. Plus, it’s hard to understand why Crabbe would suddenly offer to testify against Roman if it wasn’t part of the plea deal that was coming together at the exact same time. Or why prosecutors would rely on something as fragile as a handshake agreement to secure such crucial testimony in a high-profile case.

Legal experts say that typically such a defendant would be expected to testify first, then have his sentencing hearing, so prosecutors can be sure the defendant keeps his end of the bargain.

Meredith, who now works at the Texas attorney general’s office, did not respond to my request for comment. Crabbe declined to answer questions on this matter, citing his attorney’s advice while his parole review is pending.

The current Travis County district attorney’s office, now three administrations removed from the one that handled this case, said it couldn’t speak to decisions made in 2007.

But the DA’s office provided a statement that “our hearts go out to the family of Jennifer Crecente … and our office has urged the parole board not to have (Crabbe) released.”

Making a difference through gaming

Crecente had such a bewildering experience with the legal system that he went to law school to make sense of it. He wanted to figure out how to better help victims.

“We talked a lot about the state. We talked a lot about perpetrators. We've talked a lot about the public,” said Crecente. But unless he brought it up, “we really did not talk very much about victims,” said Crecente, who graduated in 2011 from Georgia State University’s College of Law.

By then, he helped pass a 2007 law in Texas — Jennifer’s Law — to allow high schools to award a posthumous diploma if a student died during their senior year and had been on track to graduate.

No one in Texas tracks how often such diplomas are awarded. But officials at the state’s largest school districts told me this provision has helped grieving families in their communities.

Crecente also launched a nonprofit, Jennifer Ann’s Group, to get upstream of the teen dating violence problem, to teach healthy relationship skills so that people don’t become victimized. Among high schoolers who date, 1 in 12 say they have experienced physical or sexual dating violence in the past year, yet many parents don’t know it’s an issue.

“We had the tough parent talks about drugs, and about alcohol, and about sex,” said Crecente, who saw Jennifer during summer and holiday visits at his home in Georgia. “But I didn’t talk to her about teen dating violence because it wasn’t on my radar, just like it’s not on most parents’ radar.”

Jennifer Ann’s Group pioneered a novel approach, offering prize money every year for people to design video games that promote healthy relationships. Dozens of the video games have been created over the past 15 years, reaching thousands of players a month.

MOD, a science and technology museum in Adelaide, Australia, adapted one of the games on consent into an interactive exhibit. Crecente’s group also collaborated with World Vision Vanuatu to adapt another game for use in the South Pacific archipelago of Vanuatu, getting players accustomed to asking if a person wants to hold hands, dance or receive a hug.

“We use video games because that's the way to directly reach young people, and they are receptive to the lessons learned,” Crecente said. “I think that's much more effective than watching a video or having mom, dad or your teacher talk to you about consent. When I was a kid, I didn't want that. But to play a game? Yeah.”

Crecente is proud of this work, but it is an accomplishment borne of loss, a project that can never replace the bright, generous daughter who inspired it.

Crecente wishes Crabbe got a longer prison sentence for killing Jennifer. He wishes Roman had been held accountable. Nothing can change those things now.

But with Crabbe’s parole review coming up, Crecente said, “his liberty is something I cannot fathom them granting just yet.”

Grumet is the Statesman’s Metro columnist. Her column, ATX in Context, contains her opinions. Share yours via email at bgrumet@statesman.com or via Twitter at @bgrumet. Find her previous work at statesman.com/news/columns.

More online: See a video and read the other stories in this series at statesman.com/news/columns.

About the series

This month the parole board is reviewing the case of Justin Crabbe, who killed 18-year-old Jennifer Crecente in a 2006 crime that drew renewed attention to teen dating violence.

Aug. 6: The Garden. A mother’s love turned a crime scene into Jennifer’s Garden. Now Elizabeth Crecente is fighting the killer’s request for parole.

Aug. 9: The Journals. In private writings never meant for the world, Jennifer Crecente struggled with abuse and dreamed of a brighter future.

Today: The Promise. When he took his 35-year plea deal, Justin Crabbe agreed to testify against an alleged accomplice. But the case fell apart when Crabbe withdrew his help.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Slain Austin teen's father still haunted by killer's broken promise