The Best Archaeological Discoveries of 2023

Few disciplines are as full of drama and surprises as archaeology, and this year was no exception. Archaeologists and anthropologists mined ancient genomes, excavated Roman weaponry from caves near the Dead Sea, and found a still-standing shipwreck at the bottom of Lake Huron. Click through for some of our favorite archaeological news from 2023.

5,000-year-old horseback riders

Archaeologists and bioanthropologists studying several Neolithic burial mounds in Romania, Bulgaria, and Hungary found evidence that the Yamnaya steppe pastoralists rode horses. Read more about the 5,000-year-old find.

Read more

User Needed One More Steam Point To Hit 69,000 And Valve Delivered

The Kevin Durant-Phoenix Suns era could be over before it ever really began

At $16,000, Is This Yellow 2012 Porsche Cayenne S Hybrid A Red Hot Deal?

In November, a team of archaeologists announced that a Stone Age cemetery in Finland may be three times larger than previously thought. The 6,500-year-old site may hold more than 200 graves. “[T]he notion that a large cemetery seems to have existed near the Arctic Circle should cause us to reconsider our impressions of the north and its peripheral place in world prehistory,” the group wrote in their paper. Read all about it here.

Roman swords in a Dead Sea cave

One of the most jaw-dropping finds this year came in the shape of four 1,900-year-old Roman swords and a pilum, a Roman spear. The weapons were hidden away in a cave near the Dead Sea, leading the archaeologists who found the objects to conclude that they may have been stowed there by Judean rebels.

A 3,000-year-old priest’s burial site

A team of archaeologists studying 3,000-year-old human remains in northern Peru said in August that they believe he was a priest for the region’s temples. “The find is extremely important because he is one of the first priests to begin to control the temples in the country’s northern Andes,” said a member of the team.

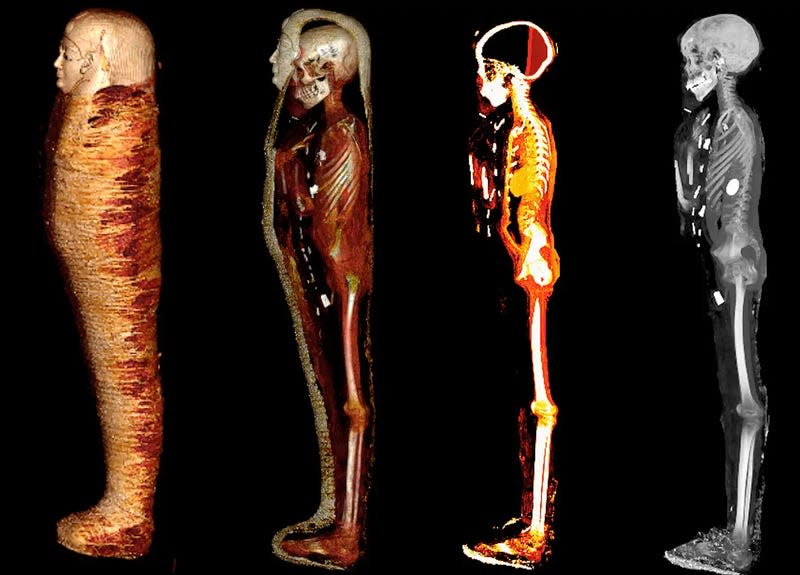

A 2,300-year-old mummy boy

A group of scientists CT-scanned the sarcophagus of a 2,300-year-old mummified boy. Their work revealed details of the “golden” boy’s health before he died, along with amulets wrapped in his linens. “This mummy’s body was extensively decorated with 49 amulets, beautifully stylized in a unique arrangement of three columns between the folds of the wrappings and inside the mummy’s body cavity,” said researcher Sahar Saleem. “Their purpose was to protect the body and give it vitality in the afterlife.”

Pompeii victims suffocated to death

X-ray analysis of the remains of six people from the doomed city of Pompeii revealed that they asphyxiated during the volcanic eruption that buried the town in 79 CE. Previous research had suggested other causes of death in the cataclysm, but the research published in August posited that inhaling toxic gases may have done the residents in.

Ötzi’s ancestry revealed

The famous natural mummy Ötzi had his genome scrutinized this year by a team of scientists who determined that the famous ‘Iceman’ hailed directly from Anatolia—or, his ancestors did. Past research had revealed Ötzi’s final meal of ibex, deer, and cereals.

Bronze Age cemetery found near space pad

One find poetically connected humankind’s present and future with our ancient past. In July, preparations for a rocket launch site in the Shetland Islands were paused when workers found an apparent cremation cemetery that dated to the Bronze Age.

Flatbread mural at Pompeii

In June, archaeologists in Pompeii revealed a beautiful still-life fresco of a food platter, including a Roman mensa flatbread that had the internet abuzz.

57,000-year-old Neanderthal carvings

A study determined that 57,000-year-old engravings on the walls of La Roche Cotard, a cave in France, were the work of Neanderthals. Read all about it (and see a remarkable fly-through of the cave) here.

Shipwrecks in the Mediterranean

In June, a UNESCO-coordinated mission revealed the discovery of three shipwrecks near Keith Reef in the Mediterranean Sea. Two of the vessels were dated to the turn of the 20th century, and one of the wrecks dated to antiquity. The team also described three Roman wrecks in their research.

Possibly the oldest smooches on record

In May, a team of researchers found cuneiform mentions of kissing dating to 2,500 BCE—4,500 years ago, making them the earliest known references to smooching. (Though, needless to say, kissing is probably a more ancient practice than that.)

A Viking hall in Denmark

In January 2023, archaeologists in Denmark found the remains of a thousand-year-old homestead, which they suspect was once a Viking hall.

Ancient plans for animal traps

In May, a group of researchers found evidence that ancient hunters in the Middle East were etching plans for their animal traps—large structures called kites—into rock.

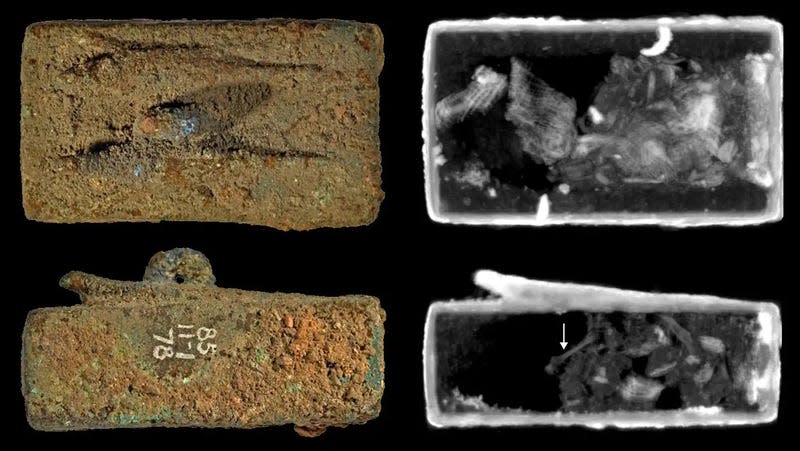

Ancient Egyptian boxes filled with lizards

A team of scientists at the British Museum X-ray imaged six 2,500-year-old animal coffins and found lizard remains within them. You can check out all the images here.

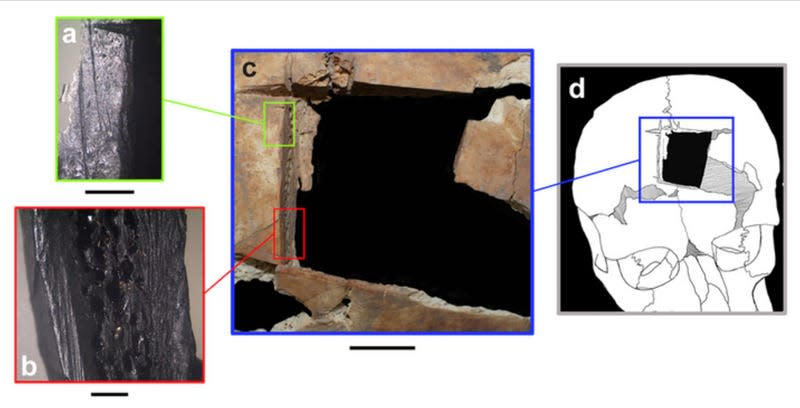

Bronze Age brain surgery

Earlier this year, a 3,500-year-old medical case reared its head—with a gaping hole in it, I might add. A team of archaeologists found that two Bronze Age brothers suffered from chronic disease, and one of their skulls had a slice cut out of it, in an apparent early attempt at brain surgery.

125,000-year-old evidence of Neanderthals butchering elephants

In February, a group of researchers published a paper in Science Advances detailing evidence of both Neanderthal hunting and butchery, in the form of 125,000-year-old proboscidean bones bearing cut marks. Imagine that: Neanderthals working together to bring down elephants.

More from Gizmodo

Fargo recap: A cruel, cynical twist justified by fantastic storytelling

Cummins Hit With $1.675 Billion Penalty For Intentionally Selling Emissions Defeat Devices

It Took 36,000 Gallons Of Water To Extinguish A Burning Tesla

New teaser photo for Joker: Folie À Deux could be 2023’s last new meme format

Sign up for Gizmodo's Newsletter. For the latest news, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.