Best friends die separate, untimely deaths, setting families on mission of hope

Jackie Brace remembers her son’s first breath.

Grant came into the world peacefully, though just a little purple.

But on this day, in the car heading north, she was consumed by thoughts of his last.

It came to mind because she found herself barely able to breathe.

As she and her husband crossed from Tennessee into Kentucky, they approached Grant's college campus, tucked into the Appalachian foothills. But she refused to look. She just couldn't.

It was there, at the University of the Cumberlands, she once sat crying at the exact spot Grant collapsed and died. His wrestling teammates had found him hours after his death.

She thought of how his final moments were spent alone.

"I try to think about how his last breath on Earth was his first breath in heaven," Jackie said.

For the Braces, the three years since Grant's death have been full of unbearable grief, endless questions and a wrongful death lawsuit. But there were glimmers of Grant in his friends who stepped forward in support during those dark days.

One of his college wrestling teammates, Max Emerson, raised funds to help pay for Grant’s unexpected funeral.

After the burial, Max, back home in Oldham County, checked routinely on Jackie, and on Grant's dad, Kyle.

Happy Mother's Day, he texted her each May.

In losing her baby boy, she gained the love and support of his best friend. Max helped the Brace family find hope in their pain.

But that was then.

Now, as the car accelerated north, the campus disappeared and Jackie exhaled. She wondered what hope truly remained.

With the Cumberland Mountains fading behind them, she thought about what she would say once they arrived at the funeral in Louisville — words that could comfort a family experiencing an all-too-familiar grief.

Arriving at Southeast Christian Church, Jackie knew this was a chance for her and Kyle to say goodbye to their son's best friend, to thank the young man who demanded accountability for Grant's death, who they'd come to believe in when they felt like they had no one they could trust.

The Braces had come to say goodbye to Max Emerson.

∎∎∎

This is the story of two friends who championed each other in life and whose demise came in devastating ways, less than three years apart.

Acts of injustice, the families say.

It's left two families, who were merely acquaintances, bonded in betrayal, left to comfort each other through their grief.

And both families are determined to make change through individual foundations that create living legacies for the young men they want to continue to share and celebrate with others.

Practice partners

The wrestlers stared at each other across the mat, thinking about their next moves.

The University of the Cumberlands touts a championship-caliber wrestling program at a small, private university known for its deep Christian values.

Off the mat, Max and Grant were typical college kids. They played video games, hung out with friends, especially over food, and were strong in their faith.

But when it came time to do the work, they were all business, holding teammates accountable and reviewing each practice in the locker room before heading home.

While wrestling may be an individual sport, on the mat, the boy from Kentucky and the one from Tennessee became the perfect union, similar in size, talent and goals.

Max and Grant were practice partners, which involves endless trust — knowing how to push limits and expose weaknesses, but never breaking that trust.

They would work on technique, drilling the same move over and over and over, until they got it right. Max wrestled in the 184-weight class. At 215, Grant was in the heavyweight class.

The way they practiced is the way they scrimmaged, believing success in matches depended on how you prepared.

“They went at (practice scrimmages) like it was a real match,” said Brady Emerson, Max’s twin, who also wrestled at the university.

Even though Grant was just a sophomore and Max was a senior, in their differences, they found a common bond.

“They were two of a kind,” said Steve Emerson, Max’s dad.

Max was still on campus, student teaching, the day wrestling began for Grant’s junior year in 2020. He was glad to be done with the program. The year before, an incident led to punishment for Max.

He had to carry 45-pound dumbbells around the campus, his father said. He would drop the weights every few steps but kept going.

Steve had retired just weeks before, after 12 years as principal of South Oldham Middle School. He emailed the university, concerned over the level of punishment, he said.

Max asked his dad why he sent the email.

"Being an educator," Steve replied, "I owe it not to you, but to any other student athlete on that campus that something like that never happens again."

Nearly a year to the day after Steve sent that email, Max was playing video games, waiting for his twin brother to get home from practice.

That’s when he heard the sirens.

'Tough times don't last...'

On Aug. 31, 2020, the morning of the first day of conditioning, Grant Brace went to Walmart and bought a whiteboard.

At the top of the whiteboard, he wrote "Motivational Quote of the Day" with the words: "Tough times don't last. Tough people do."

He set the board in his locker and joined his teammates for conditioning.

As the workouts wound down, on a run back to the wrestling gym, the team stopped at a spot known as Punishment Hill. Then, they began sprinting up the steep 200-foot-long incline.

Grant sprinted up the hill again and again in the late summer heat.

But eventually, he sat down, then laid down.

Grant suffered from narcolepsy, a sleeping disorder that often left him feeling drowsy during the day. He took medication, a stimulant, for it, and it often left his mouth dry. He needed water.

According to witness interviews conducted by the Williamsburg Police Department and the allegations presented in the Brace's resulting lawsuit, teammates said coaches told them they were not permitted to touch their water bottles, and the following took place:

The coaches began to berate Grant for his performance, telling him to leave the hill and clean out his locker. Grant left the hill, but returned a few minutes later, telling his coaches he wanted to prove himself to them and the team.

Tough times don't last. Tough people do.

He continued to attempt sprints up the hill, appearing unsteady on his feet. While a short team meeting took place, Grant held onto a small tree limb, swaying back and forth.

The team walked to the wrestling gym, about 100 yards from the hill, to shower.

Inside, Grant laid on the wrestling mat and began to beg for water. Eventually, he began acting erratically and charged at a teammate, tackling him to the ground. He started to speak gibberish, then ran out of the gym.

Security footage shows Grant running out of the wrestling gym to another building on campus, where he tried with both hands to pull open the locked doors. He kicked the door and ran out of the camera’s view.

Hours later, some of his teammates found Grant collapsed on the lawn near the campus fountain, vomit in front of him, his hands still clutching the grass.

He was dead from exertional heat stroke.

'Do it for Grant Brace'

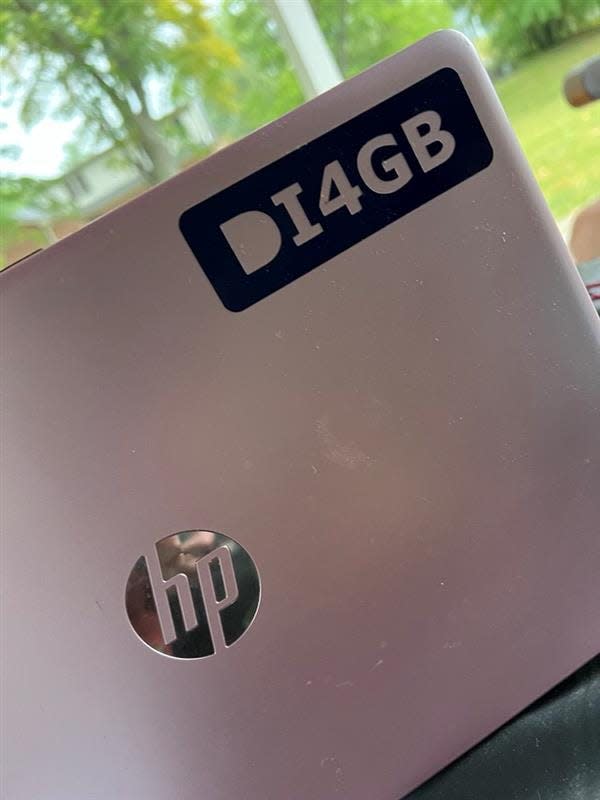

DI4GB.

The message was subtle but had a big impact: Do it for Grant Brace.

Max Emerson sold the bracelets with the small inscription around campus to help raise funds for Grant's family. He slipped one on his right wrist and never took it off.

The bulk of the money went into the GoFundMe for Grant's funeral, but even after it closed, Max continued to sell the bracelets, asking if he could deliver the funds personally to the Braces at their home near Knoxville, Tennessee.

When he did, they sat on the Brace's back patio and talked for hours. Kaylee, Grant's older sister, had heard a lot about Max but had never met him until that day.

"He was a genuine guy," Kaylee said. "It was obvious he was upset about what happened to Grant."

Jackie sent him home with leftovers, just like she had often done with Grant.

"It gave us a little bit of therapy getting to talk to him, someone who knew," Jackie said.

When the Braces' wrongful death lawsuit ended, Kyle called Max. They wanted him to know they had fought for the amount of the settlement to be public in an attempt at the accountability Max wanted from his former team. The Braces settled with the University of the Cumberlands for $14.1 million.

In a statement, the university said, in part, it believed it could defend the claims made in the lawsuit, but "the legal process would have been long, difficult and costly, ending years from now in a trial with an uncertain outcome."

A criminal case remains open.

Since high school, Max's goal was to return to Oldham County and become a teacher and wrestling coach. When he achieved that later in 2020, he invited the Braces to come and watch his team. Jackie hadn't watched the sport since Grant's death. It brought too many painful reminders. But she wanted to do it for Max ... and Grant.

After this season ended, Jackie promised she would one day come and watch.

'Whenever you're ready,' Max said, 'you get a front-row seat.'

'We could die tomorrow'

On a July day earlier this year, Max, Brady and their mom, Chandra, walked around the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C., admiring the art.

Both Brady and Max, 25, had joined their parents and a long line of family members in becoming educators. They were in D.C. over the holiday for a national teachers' conference.

"In 20 years, will you look back and think about all these moments and all the fun you are having in D.C.?" Chandra asked the boys.

"We don't know," Max responded. "We could die tomorrow."

"Max, you're right," she said.

Two days later, the texts to his mom were sent frantically.

Chandra didn't understand the jumbled words that were intended to say, 'Help, I'm being robbed at gunpoint.'

She was still asleep when Max left the room at around 7:15 a.m. for a workshop at the Library of Congress. He was on his way to catch the train when a man approached him in the subway and, based on video recordings, seemed to ask for money.

"Max pulls out his wallet and handed him cash," Steve Emerson said.

It wasn't enough. The man held Max at gunpoint for more than 20 minutes, while they walked across campus.

Security footage shows Max with his hands up.

That night, in a camper in Alabama on the way back from celebrating Independence Day, Jackie Brace's phone illuminated with a text.

Did you hear about Max?

No

He was shot.

The darkness crept in and she began sobbing.

"I know Grant would have been devastated just as much as Max was," she said.

A mission of hope

Hundreds of people filed through Southeast Christian Church and hugged Chandra, who wore a blue shirt emblazoned with the words "Champions Find A Way" — Max's motto for how to approach a barrier.

Thank you for being here.

We appreciate you for coming.

Chandra felt numb, on autopilot. But then she saw her, near the end of the line. A mother who understood exactly what she was going through.

Jackie Brace looked back at Chandra, knowing the painful days the family had ahead.

"I did not adequately hug her enough," Chandra recalled.

Both families still have unanswered questions. Some they'll never know. Others they hope to find once D.C. police complete an investigation.

"The day he was killed in D.C., the only thing I wanted was the (blue bracelet) he wore that he did for Grant," Chandra said. "We're assuming the police has them."

Nearly three months later, Chandra sent a text to Jackie. Both families were working on foundations.

"Can you believe three years later, we'd both be here?," Chandra asked.

The Grant Brace Foundation will work to educate on the signs and symptoms of heat stroke through the BRACE Protocol, which is a quick checklist on how to handle an exertional heat stroke.

Max's foundation, Champions Find a Way, will offer financial support to young adults who face barriers in achieving their personal or educational goals.

"That one act of violence shattered a school, a community, a family, but I think that’s the reason why we decided to do the foundation," Steve said. "So that we can help make a difference, spiritually, financially, whatever."

And, in turn, it's Grant supporting Max.

Out of Grant's wrongful death settlement, the Braces' gave money to the Emersons, which is going to help start Max's foundation.

"As broken as we are, and we’re never going to get over it, we are going forward and making something happen," Chandra said.

"My hope is that what happened not just to Grant, but even to Max cultivates change," Jackie said. "Those two young men had figured out something. They were OK with being different and figured out a way to navigate this world. How can we not continue to share their goodness, their love?"

After writing a message to Max on his casket, she walked to take her seat. A blue bracelet in Max's honor rested on the chair. She slipped it onto her wrist — next to the one for Grant. Their mission of hope was just beginning.

Safer Sidelines: An investigation into sudden death in youth sports

Stephanie Kuzydym is an enterprise sports reporter, with a focus on the health and safety of athletes. She can be reached at skuzydym@courier-journal.com. Follow her for updates on Twitter at @stephkuzy.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: Parents form foundations as legacies of Grant Brace and Max Emerson