Bestselling book recounts Evansville's racist history with the Ku Klux Klan

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

EVANSVILLE – The Rev. A.M. Couchman was about to start his Sunday night sermon when a gang of robed and hooded men threw open the door.

There were about 20 of them. They didn’t speak as they moved up the aisle of Central Methodist Episcopal Church on Mary Street in Evansville and offered the minster something unexpected: a pile of cash.

After a quick prayer they vanished, driving off into night with their license plates as shrouded as their faces.

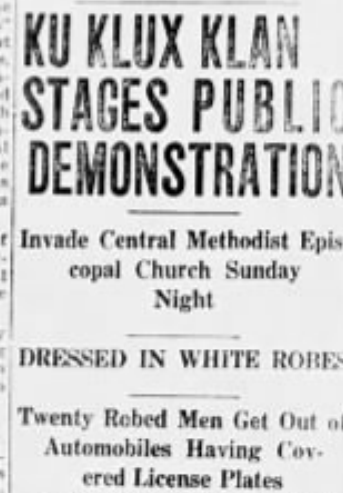

The Evansville Courier reported on the spectacle the next morning in its March 27, 1922, edition. They called it the city’s first-ever public appearance by the Ku Klux Klan.

“Their visit was spectacular,” a reporter wrote.

Reading the paper in his cramped room at the Vendome Hotel, D.C. Stephenson agreed. A smarmy drunk who’d spent years bouncing from town to town, he’d only been in Evansville a short time, trying everything from sales to a Congressional run to make a name for himself.

His main gig, however, was working as a recruiter for the newly resurgent KKK, making $12 a week to entice northerners into what had once been a mostly Southern hategroup.

The Klan had been trying to recruit people based on hatred. But the incident at Central Methodist showed Stephenson a different way. He eventually paid off more than a dozen Evansville Protestant minsters, who in turn sang the KKK’s praises in front of their packed congregations.

Get the pastors on your side and recruiting would take care of itself, Stephenson realized. All it would take was “a bribe and a bit of Bible talk.”

That quote comes from “A Fever in the Heartland,” a best-selling book of history by Pulitzer Prize-winning author Timothy Egan that chronicles how the KKK swept through Indiana in the 1920s and gained control of countless city governments, the statehouse and even the governor’s mansion.

It’s received rave reviews from the New York Times, Washington Post and NPR, among several others. And Evansville stands at the heart of it.

Egan used Courier & Press archives and reams of other research to track the Indiana Klan’s birth in Evansville and how it metastasized to put the state on the brink of racist theocracy.

It also chronicles the rise of Stephenson, an eventual Grand Dragon and amoral monster who beat and bit and raped his wives while nursing dreams of becoming president of the United States. And he could have achieved it – until a brave Indianapolis native named Madge Oberholtzer took him down.

“Heartland” came out in April 2023 but has lingered in the national conversation for 10 months, especially as its subject matter remains relevant.

It depicts the Evansville of the 1920s as the most segregated city in Indiana: an immigrant-fearing, white-heavy river town that, despite its perch above the Mason-Dixon line, was more south than north.

“Evansville was ripe for the Klan. … And D.C. Stephenson was the ideal missionary. He had magnetism, unbridled energy, and a talent for bundling a set of grievances against immigrants, Jews, Roman Catholics, and Blacks into a simple unified pitch that made sense of a fast-changing America still dazed by the Great War,” Egan writes.

“… In his experience, you didn’t have to lead a man to hate. Just show him the way and he’d do it on his own.”

What ‘A Fever in the Heartland’ says about Evansville

The formal charter for Evansville’s wing of the KKK was signed in May 1922, the first such chapter in the state. The Klan would eventually spread to all but two of Indiana’s 92 counties – the heaviest saturation of any state in the country.

But Evansville’s problems began long before that.

Accounts of violence and racism date back to the city’s founding in the 1800s. In 1903, 12 people were killed and several buildings were vandalized in mostly white riot that lingered for days after a Black man named John Tinsley was accused of shooting and killing a white police officer.

That still haunted the city by the time Stephenson showed up, Egan writes. It was especially foreboding for the 6,000 Black residents living without electricity or indoor plumbing in the tenements of Baptisttown.

Then there was the incident in 1921, when a different mob – this time armed with clubs – chased a group of Irish and other immigrants out of town, despite the fact many of them had helped build what would eventually become the Wabash and Erie Canal.

That same year, President Warren G. Harding gave a speech calling for an end to lynching and racial inequality. When he died two years later, some people in Evansville responded by planting a burning cross on the banks of the Ohio.

“Most of the town was white, native born and Protestant, like Indiana itself,” Egan writes. “That was the first thing that got (Stephenson’s) attention.”

He’d soon take full advantage. By July 15, 1923, more than 10,000 people flooded into Mesker Park for a Klan rally, Courier archives show. Men, women and children alike stayed for a parade, picnic and speeches by people who refused to release their names – and who the papers didn’t identify.

In 1925, Herbert Males was elected mayor. A year later he’d sit in front of the U.S. Senate and openly admit he was a Klansman – a scene taken from a 2018 Courier & Press article and depicted in “Heartland.” Males had prominent judge Phillip C. Gould and Evansville Police Chief William Nolte on his side.

That same year, Ed Jackson was elected governor. Stephenson attended his inauguration as a guest of honor. He also had a sympathizer in former governor/eventual U.S. Senator Samuel Ralston.

As backward people took office, backward laws followed. Indiana passed the world’s first eugenics sterilization law, targeting “idiots, imbeciles and confirmed criminals.”

You could find burning crosses in front of Black homes and Jewish synagogues. Klansmen marched in Fourth of July parades and played Santa at Christmas. By the mid-20s, a quarter of Vanderburgh County men counted themselves as members, although the number could have been much higher. Statewide, it was closer to 30, Smithsonian Magazine reported.

“The Klan owned the state and Stephenson owned the Klan,” Egan writes. “Cops, judges, prosecutors, ministers, mayors, newspaper editors – they all answered to the Grand Dragon.”

Stephenson claimed to have a private phone line to President Calvin Coolidge. And around his inner circle, he’d utter a deranged but not-untrue statement: “I am the law in Indiana.”

Madge Oberholtzer

Like the rest of the Klan, Stephenson pitched himself as a pristine Christian who revered family and abstained from alcohol in the Prohibition-riddled U.S.

In reality, he was a heavy drinker and wife-beater.

He eventually moved to a sprawling estate in Irvington, Indiana, but back when he lived in that small room in the Vendome, he crafted a prison cell for his first wife, Violet. One evening in 1922, he punched her in the face so hard she nearly passed out, Egan writes. Still he kept on, kicking her in the ribs and running his fingernails over her face until blood stained the floor.

In 1925, he passed his violence on to a woman he met at Jackson’s inauguration.

Madge Oberholtzer wasn’t shy. In 1917, while attending what was then Butler college, her classmates sarcastically called her a “timid little creature with a baby voice,” but she was anything but. While men vanished into the war fronts of Europe, Madge seized upon new job opportunities, becoming a clerk, office manager, and eventually a state employee.

“Madge didn’t need a husband or a church to tell her how to live,” Egan writes. “She dated frequently and was selective, in no hurry to marry. … She was a woman of her age, pushing back against centuries of caged convention.”

When she bought a Model T in 1923, she and her friend Ermina Moore went proto-Jack-Kerouac and embarked on a cross-country drive to California. Sometimes the roads weren’t even paved, and they spent evenings camping in the elements or sleeping in roadhouses.

By the time she returned home, things at work were looking grim. She worked at a lending library for poor school districts in the Indiana Department of Public Instruction, and legislators were hellbent on eliminating her position for budgetary reasons.

She needed help. And when she read a laudatory profile on Stephenson in the Indianapolis Star, she hoped he could help.

After meeting at the inauguration, Stephenson began calling her. And on March 15, 1925, he summoned her to his house in Irvington to talk about a book Madge wanted to write.

But it was a ruse. A drunken Stephenson and a team of equally inebriated bodyguards kidnapped her and ushered her onto a train to Chicago, where Stephenson attacked her, biting and chewing on her skin until she was bloody and disfigured. She passed out from the pain.

The hell continued at a hotel in Hammond. When Stephenson finally fell asleep, she talked one of her captors into taking her to a pharmacy. And that’s where she bought the poison.

She swallowed mercury tablets that set fire to her internal organs and left her spitting up blood. Realizing the state she was in, and refusing to take her to a hospital, Stephenson’s bodyguards dumped her back at home. They claimed she’d been in a car accident.

‘When will this ever change?’

Rumors of Stephenson’s crimes began to fly. And as Madge lay inside her house dying, crowds gathered on the lawn.

Two weeks after the attack, when it became clear she couldn’t recover, Madge’s attorney drew up a 3,000-word statement written in her voice. It revealed everything about D.C. Stephenson.

He was eventually charged with causing Oberholtzer’s death. And although his attorneys did everything they could to trash her character, the once-most-powerful man in Indiana was found guilty and hauled off to prison for 25 years.

The punishment did little to change his ways. When he was finally released, he bounced from Tulsa to Illinois to a few places in between. He’d go to back to jail for ghosting his parole officer and then for trying to lure a Missouri teenager into his car.

By the time he landed in Tennessee, few of the locals knew about his heinous past. When he died in 1966, the news didn’t reach the national press until 12 years later, when the Louisville Courier-Journal broke the story.

The Klan’s power soon dissolved in Evansville and across the U.S. But after Males lost his bid for re-election in 1929, it would take the city another 94 years to elect its first Black mayor, Stephanie Terry.

On the morning of her election last year, she shared a picture of herself staring at the city’s wall of mayors on the third floor of the Civic Center. It featured 33 framed photos of white men – a former Klansman included.

“I walked past that wall thousands of times and really said to myself, ‘When will this ever change?’” she said at the time.

Signs of that troubled past remain.

Evansville was one of three cities profiled in the Washington Post in 2022 for their backing of racist presidential candidate George Wallace 50 years earlier. The article drew comparisons to the city’s even more fervent support of Donald Trump in 2016 and 2020.

Reporter Peter Jamison talked to an Evansville teacher who compared the city to the “sunken place" from Jordan Peele's "Get Out." He also chronicled recent racist incidents, including an Olive Garden customer who refused to have a Black server in 2020, and an argument between city councilors that led 4th Ward Democrat Alex Burton to call two other councilors “Dixiecrats.”

In 1924, U.S. Rep. William E. Wilson – a former Vanderburgh County deputy auditor – championed a huge piece of legislation that brought funding for a bridge over the Ohio River. But when he ran for re-election later that year, he lost handedly.

The reason, Egan writes in his book, is that Wilson refused to back the Ku Klux Klan.

His home was vandalized. Neighbors stopped speaking to him. Strangers even threatened to kill him and his family.

“We’ve gone a long way in this country. But apparently we haven’t freed men and women of their suspicion of each other. Their prejudices. Their intolerance,” he reportedly told his son. “I think it’s going to be a big battle in this century. My little fight here in Indiana is just a preliminary skirmish.”

This article originally appeared on Evansville Courier & Press: 'A Fever in the Heartland' recounts Evansville's history with KKK