‘Beware the Soviet creature’: the ‘inhumanity’ of life in Nazi captivity

Our new book, OST: Letters, Memoirs and Stories from Ostarbeiter in Nazi Germany, is a mosaic assembled from collective memory. These memories belong to the “Eastern workers”, known in German as Ostarbeiter: the 3.2 million Soviet citizens deported from German-held territories during the Second World War and forced to work for the Third Reich.

Until recently, too little was known of their fates. This story of their deportation, life in Germany and return to the USSR has been assembled from interviews, memoirs, documents, letters and photographs – all of which have been collected over the last 30 years by the Russian historical and human-rights organisation, Memorial.

The journey to the Third Reich, in particular, stood out as one of the most dramatic chapters in the stories told by the Ostarbeiter. Many had been just 16 or 17 years old at the time, and some were younger. Torn from their families and subjected to terrible travelling conditions, they wrestled with fears about what awaited them as captives of a frightening and pitiless enemy.

‘We were herded into a chamber with little objects in the ceiling’

The shock of the experience was so severe that some Ostarbeiter were unsure how long they had travelled, or where they or their families disembarked. In the archive, we have one postcard, dated July 23 1943, sent from Gotenhafen (occupied Poland) to Kitaigorod (Ukrainian SSR):

Good afternoon, my precious Mummy!!! First of all, I am sending you my heartfelt greetings! Mummy, I’m in Poland. We are near the city of Gotenhafen and work right by the Baltic Sea. […] Mummy, I got separated from the others I came with, and don’t know where they went. – Valya.

Vadim Novgorodov (from Taganrog, Russian SFSR) recalls that when his train stopped over in Poland, he witnessed Jews who had been brought from the ghetto being forced to clean the train: “At Peremyshl I saw how the Jews were treated – they appeared to be Polish Jews. They were forced to wash out the wagons once the trains had been unloaded – the guards harried them with sticks.”

The trains usually didn’t stop for long until they had crossed into another territory; most Ostarbeiter remember that they first broke their journey in Poland. Many of them mentioned what took place in the cities of Peremyshl and Poznań: the fear of epidemics was so strong among the Germans that the new arrivals had their hair cut and clothes boiled. Aldona Volynskaya (from Novoukrainka, Ukrainian SSR) also remembers a medical inspection: “A man led me off somewhere. I was naked, and he poured water on me and smeared me with some cream. It was so humiliating.”

Iraida Zhukova (from Krasnoye Selo, Russian SFSR) was deported alongside her mother at the age of 10 in August 1942. She recalls:

Everything was dingy and dark. Everyone was made to undress – men and women together – and once naked, we were led off down a corridor. One German sat on one side, and another sat opposite. They held little sticks in their hands, which they used to inspect all the hairy parts. I felt so uncomfortable in front of the men.

Next, we were herded into a chamber with little objects in the ceiling. I heard the adults say: “Perhaps they are about to turn on the gas.” There was such a sense of terror! And then suddenly water came out from those little objects. Everyone breathed a sigh of relief – it was a shower.

(It is worth noting that word of the gas chambers in the Nazi concentration camps could not have reached the Ostarbeiter by 1942. The 10-year-old Iraida’s “memories” of fear must have been formulated at a later date.)

Very few could remember their first few hours in Germany with clarity; for most, they passed in a frightening blur. Antonina Sizova (from Gdov, Russian SFSR), deported in summer 1943, remembers:

We didn’t know where they were taking us. We were unloaded in the drizzling rain and organised into columns in silence. They escorted us with dogs to a building where we found others like ourselves. Everybody was given a coloured patch to attach to the left-hand side of their chest, either red, yellow, green or blue. We were given yellow patches, which assigned us to the distribution camp.

Raissa Pervina (Baranovichy, Byelorussian SSR), deported in spring 1942, found herself at a camp that housed Soviet prisoners-of-war. She describes the terrible living conditions:

The camps here were large, and surrounded by barbed wire. […] There were barracks with stacks of greatcoats heaped outside that had belonged to our deceased prisoners-of-war. There was no lavatory; just a hole under one of the watchtowers. And you were expected to use this hole in full sight of the guard, who might just take a pot shot at it for fun, to watch you get splattered with excrement.

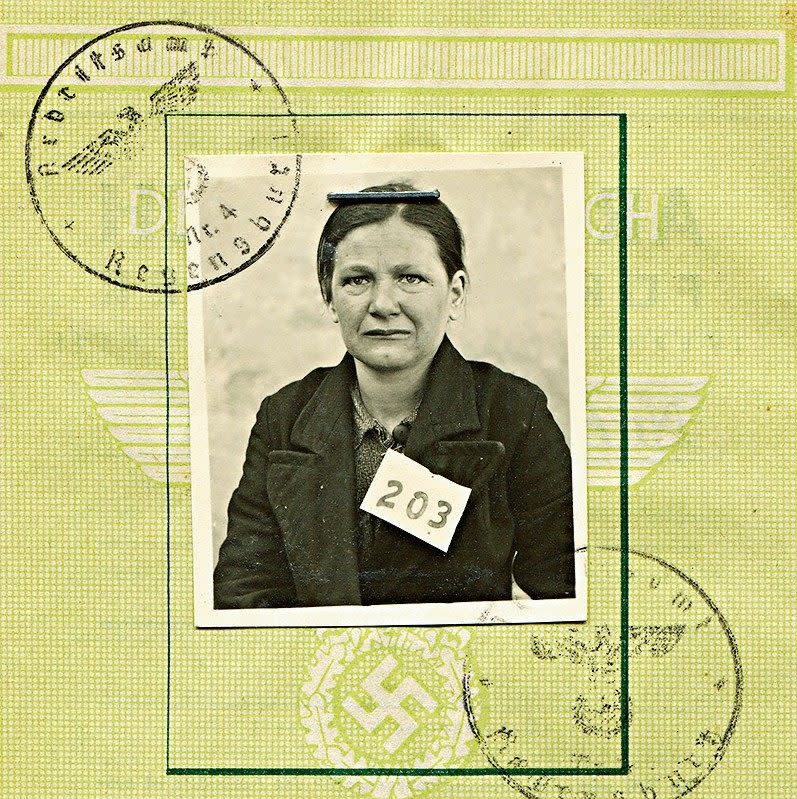

Some remembered being photographed and having their fingerprints taken. Prior to this, a cardboard panel displaying a number would be hung around their neck. Varvara Kramarenkova (from Sevastopol, Russian SFSR), deported in September 1942, says that this was “the first thing that really crushed our spirits”.

‘Nobody bought me on the first day’

The Ostarbeiter had clear memories of how they were assigned to their workplaces. The process was usually carried out at the distribution camps, where labour exchanges had been established for this purpose. They could be allocated to any number of jobs: some were sent to work in the mines, factories or construction, while others were dispatched to work for farmers, or as domestic helpers. Work conditions, food provision, access to medicine and daily life varied depending on which of these labour categories they were assigned to.

Once the Soviet arrivals had been categorised, representatives from a firm or enterprise would come and – for a fee – choose workers. They were generally most interested in the candidates’ physical conditions; many of the Ostarbeiter were too young to have professional qualifications and, in most cases, their education had been rudimentary.

Anna Kirilenko (from Rostov-on-Don, Russian SFSR) remembers:

They looked at us to see whether we were in good physical health, and then checked whether our arms and legs functioned properly. For the factory where I worked, they chose young, agile people of a light build. […] The bigger, stronger, fitter ones were assigned to heavy manual labour.

And Anna Sechkina (from Volodarskoye, Russian SFSR) recalls that “not everybody was selected – the elderly, and children younger than 10, were rejected. The managers said that feeding them would be a waste of bread.”

For many, the selection process was redolent of a slave market, where labour was purchased and sold. Lev Tokarev (from Peterhof, Russian SFSR) was deported in 1942. He says:

When we were taken to the labour exchange, everybody was chosen, but nobody took me. I was scrawny, and was left standing on my own. I could see an elderly man and woman standing nearby, staring long and hard at me. Eventually they walked over. “Are you a Jew?” they asked. “No, I’m Russian,” I replied. They talked and bartered, before eventually handing over some money to somebody. Then they took me away to work for a large-scale gardening enterprise.

The sense of humiliation was compounded by the fact that the well-dressed and well-fed “buyers” often regarded the Soviet arrivals as chattel and “savages”.

‘I had to sew the badge to my chest and wear it at all times’

Nonetheless, at first, to the Eastern workers arriving from the hunger and deprivation of their war-torn homes, Germany appeared clean, prosperous and orderly. Anna Odinokova, whose family formerly worked on a kolkhoz in Chernigov (Ukrainian SSR), describes her first impressions of Germany: “There were flowers on the balconies and all along the sides of the roads. It was beautiful – I had never seen anything like it! We had flowers, but not in such abundance.”

The better-educated girls were taken aback by the outward appearance of the Germans. Aldona Volynskaya says: “Even the people at the railway station looked to me as though they had just stepped off the pages of a fashion magazine. It was a different world.” And when Victor Zhabsky, a teenager from Novocherkassk (Russian SFSR), first laid eyes on Germany, he described it as “a little corner of heaven”: “I tell you, Germany must have been created as a paradise. […] Everything was clean, beautiful and tidy.”

Among this milieu of prosperity, however, the Soviet arrivals had also to contend with animosity and aggression. Nikolai Bogoslavets (from Zenkov, Ukrainian SSR) remembers:

The Germans would line the streets when we were being escorted back from work. Each would stand on his own doorstep, and the children would fire little stones at us from their catapults. The Germans would laugh when one found a target.

The Ostarbeiter had to wear a small square of fabric bearing the white letters ‘OST’, set against a blue background, on the right-hand side of their chests. Refusal was punishable by a fine or even a prison sentence. The badge marked them out as second-class citizens, deprived of their civil rights. It is not coincidental that many of them referred to these pieces of cloth not as “badges”, but as “patches”, “cloths”, “rags”, “swatches” or “tags”. (Very few of the Ostarbeiter we interviewed, however, could show us their OST badges; on returning home to the Soviet Union, many had thrown them away.)

The letters “OST” soon became symbols of ignominy, mockery and danger. Anna Odinokova worked for a farmer in Lower Silesia and remembers: “I was told to sew it to my chest and to wear it at all times. On no account was I to remove it, or I would be punished.” Zoya Yeliseeva (from Dzhankoy, Russian SFSR), who worked in a textile factory in Frankfurt am Main, recalls: “It was so demeaning – we weren’t used to being marked out like that.” Tatiana Teplova (from Griva, Russian SFSR) was a railway worker: “Do you know what we said OST stood for? ‘Beware the Soviet creature.’” (She has created a ‘backronym’ from that phrase, which in Russian is Ostergaisya Sovyetskoi Tvari.)

Despite the risk of fines or punishment, the Ostarbeiter would remove or hide their badges when they wanted to regain a sense of freedom. Antonina Maxina (from Rostov-on-Don, Russian SFSR) says: “If I managed to get into the cinema, I would take off my OST badge.” Similarly, Anna Kirilenko recalls that her employer would tell her to hide or remove hers when they went into town together, so that the police wouldn’t bother them.

In the spring of 1944, the Germans began to relax the rules for foreign workers, and the police became less stringent in enforcing the wearing of OST badges. By then, however, the Red Army was already pushing the German forces back across Eastern Europe. In October that year, a Soviet government department was established to deal with the “matter of repatriation”.

This process began soon after Germany’s surrender in 1945. Repatriation was compulsory, not voluntary. In line with pacts made at the Yalta Conference, it was agreed that each and every one of the Ostarbeiter, without exception, and irrespective of their personal wishes, should be forced to return to the Soviet Union.

Translated from the Russian by Georgia Thomson. OST: Letters, Memoirs and Stories from Ostarbeiter in Nazi Germany is published by Granta today at £35