The Biden Climate Bill: Will It Save Us?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The success of President Joe Biden’s climate bill, which he’s slated to sign Tuesday, will not be judged by polls, or by the price of gas at the pump, or by the ferocity of the next hurricane that hits the Gulf Coast.

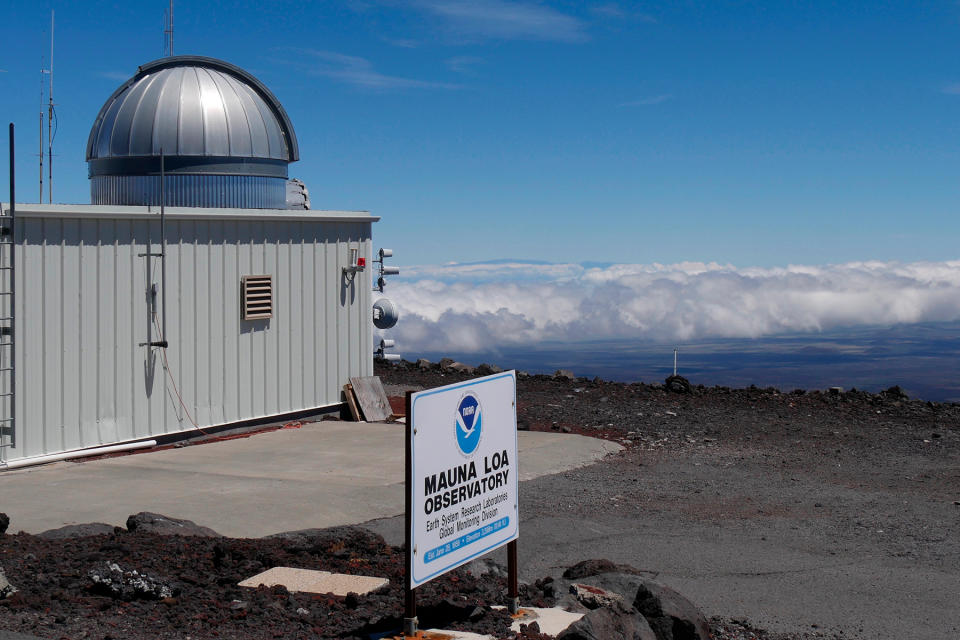

It will be measured in the clear air high above the Pacific Ocean at the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii. In 1958, when scientist Charles Keeling began measuring CO2 in the atmosphere at Mauna Loa, the level was 316 parts per million (250 years ago, before the industrial era, it was 280 ppm). Today, 63 years later, the CO2 level is 416 ppm, an increase of roughly a third over pre-industrial levels. It’s the accumulation of this molecule that’s trapping heat in the atmosphere, causing oceans to rise, forests to burn, and extreme heat waves to cook cities. By measuring CO2, Keeling began what amounts to a diary of our march toward climate chaos.

More from Rolling Stone

It's Real Now: Joe Biden Has Signed the Climate Bill Into Law

The 'Dark Brandon' Meme Has Died From a Terminal Case of Cringe

What’s most remarkable about The Keeling Curve, as the chart of atmospheric CO2 levels is called, is it’s unbroken ascendence. None of the significant events in our decades-long fight to reduce emissions has made a dent in its upward curve — not NASA scientist James Hansen’s 1988 congressional testimony declaring that the human fingerprint on the climate had been detected; not the Kyoto Protocol in 1992 when nations of the world came together to commit to reducing CO2 pollution; not Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth or Greta Thunberg’s global climate strike in 150 countries or UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres warning that we are “sleepwalking into a climate catastrophe.” From the point of view the atmosphere, which is really the only POV that matters, none of this has had any detectable influence.

The big question is: Will this climate bill — officially known as the Inflation Reduction Act — change that? Will it halt the ever-upward march to a hotter and more inhospitable planet? Or, to put it another way, is it enough to save us? Or at least to begin to save us from the consequences of 250 years of hell-bent consumption of fossil fuels?

By any measure, IRA is a hugely important step in the fight for a hospitable planet. According to models, by 2030, the legislation will reduce the U.S. emissions by forty per cent compared with their levels in 2005. That is close to the fifty percent reduction by 2030 President Biden committed to last year, and puts Biden’s goal of net-zero emissions by 2050 within the realm of possibility. If IRA achieves this, or anything close to it, it will end the reign of fossil fuel thugs and rewire our future.

IRA will achieve these reductions mostly through tax credits and rebates on clean energy. That in itself is a radical change from previous climate initiatives. Gone are old ideas of taxing carbon or setting up a CO2 trading regime or lectures about the importance of being a good citizen for Planet Earth. This is pure pragmatism. “Whereas President Jimmy Carter once pushed clean energy as a matter of personal, moral responsibility,” Steven Mufson wrote in the Washington Post, “the new bill treats climate change as a pragmatic pocketbook matter of consumer rebates and corporate tax incentives.”

If that sounds modest, especially given the scale of the climate crisis – well, it is. In sheer dollar amount, the investment is modest too. IRA calls for spending less than $500 billion over a decade, compared with the American Rescue Plan’s $1.9 trillion in a single year. And IRA will, in theory, reduce the deficit too.

So how can such a modest investment have such a big impact? “The answer is that right now we’re sitting on a sort of cusp,” economist Paul Krugman argues. Renewable energy tech has made revolutionary progress, and renewables are already cheaper in many areas than fossil fuels. “A moderate push from public policy is all that it will take to transition to a much greener economy,” Krugman says. “And the Inflation Reduction Act will provide that push.”

Susan Cobb/NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory/AP

To put it another way, this climate deal is all about ripple effects and momentum. In theory, it works like this: subsidies and rebates will give home heat pumps the little push they need to replace gas furnaces, which in turn will reduce demand for natural gas, which will close down the fracking operations that leak methane into the atmosphere. Subsides and rebates will also give electric vehicles the extra shove they need to replace internal combustion engines, which will cut the demand for oil and that will in turn push companies like ExxonMobil and Shell and BP to accelerate their investments in clean energy. The faster this happens, the bigger it snowballs, and the faster the world is transformed. As writer Alex Steffen puts it, in what may be the single most important maxim of the climate era, “Speed is everything.”

As the dynamic shifts, it will inevitably change how money flows in politics. In 2020, the oil and gas industry campaign contributions hit a record-breaking $140 million, much of it funneled through front groups and other dark money portholes, with more than two-thirds of it finding its way to Republican candidates and committees. But as the fossil fuel empire declines, that flow will be diverted, or at least spread to a broader spectrum of political players. Instead of dark money flowing to build new coal plants, dark money will flow to build new wind farms. And that’s a kind of progress, right?

The increasing inertia of clean energy also changes the constituency for further climate action. “One of the bill’s many benefits is that it could finally break the partisan logjam,” Elizabeth Kolbert observed in The New Yorker. Today, Kolbert points out, roughly five hundred thousand Americans work in the petroleum industry, and another two hundred thousand work in the natural-gas sector. That’s a big constituency for maintaining the fossil-fuel-powered status quo. “If the IRA functions as hoped,” Kolbert argues, “it will create hundreds of thousands of jobs in clean energy and, with them, a growing constituency for climate action.” This broader constituency will also encourage policy changes at the state and local level, which will further drive emissions reduction.

In theory, all this will carry over to international climate negotiations and give the U.S. more authority to push other nations – including China and the EU – to do more to cut their own CO2 pollution. This is problematic on many levels, especially given the U.S.’s increasingly hostile relationship with China. But the hope is that more ambitious U.S. leadership will inspire more ambition from other nations and creating what amounts to a global clean energy tsunami.

All this momentum will build on itself, helping people see not only that political action works, but that cutting fossils fuels is a clear and direct path to a better world. One with less pollution, more livable cities, better paying jobs, and more justice and equity.

So that’s the hopeful scenario. There are, of course, other less inspiring ways of looking at how this may play out.

First, as one friend who has worked on climate policy for more than 30 years puts it, “the question arises as to whether rebates/tax credits are enough of a piranha to really eat into greenhouse gas emissions quickly?”

Energy modelers agree that the potential for CO2 reductions from these rebates and tax credits are in the realm of forty percent by 2030. But models aren’t the real world. (As a British statistician famously put it, “All models are wrong, but some are useful”). It could be that the reductions are understated – for example, the $27 billion that IRA pours into the formation of a national from green bank to fund clean energy and infrastructure projects isn’t in the models. But the models also make a lot of assumptions that may not fit well with reality. Just because in the hyper-rational world of the models it makes sense for people buy EVs, it doesn’t mean that they will. There are a thousand reasons why: maybe the backlog is too long, or they just like the purr of internal combustion engines. Ditto with transmission lines and other big infrastructure projects that the models assume will get built without NIMBY lawsuits and other delays. “We’re taking informed guesses with this stuff,” Ben King, an associate director at Rhodium Group, which analyzed the IRA, told Climatewire. “Human behavior is tough to model.”

Second, the fossil fuel thugs are not going to disappear quietly into the night. Exhibit A: the permitting deal that Senator Joe Manchin cut to keep the Mountain State Pipeline alive in West Virginia. There is also a mandate tucked into IRA that ties renewable development on federal lands and waters to auctions on millions of acres to fossil fuel drillers.

A movement is growing in fossil fuel states to punish banks that curtail fossil fuel investment. Other ploys are more subtle. In Texas, Occidental Petroleum is angling for hundreds of millions of dollars in tax breaks to build carbon capture plants that pull very modest quantities of CO2 out of the atmosphere but will allow them to market “net-zero oil.” Anybody want to bet the future on that Orwellian phrase?

Third, the climate crisis is a global issue. No matter what the U.S. does, it can’t make much progress alone. How long will China and India keep building new coal plants and Australia keep opening new mines? Will the Democratic Republic of the Congo allow oil drilling in protected wildlife habitats? How will Russian president Vladimir Putin’s manipulation of oil and gas markets impact the consumption of fossil fuels in the EU? This is not just an issue of political leadership, but of competing interests. If the global demand for beef continues to climb, for example, it means more rainforest in the Congo and Brazil will likely be cut down for pastureland, which will lead to less CO2 absorbed by the rainforest, which will accelerate atmospheric warming, which will in turn push the rainforest itself closer to collapse. It’s not a feel-good feedback loop.

Finally, when it comes to climate impacts from rising levels of CO2 in the atmosphere, it’s very late in the game. Until we get to zero emissions, temperatures are going to keep rising. And due to the warmth that is already built up in the ocean, even after we hit zero emissions, sea level rise is going to continue for a long time to come. Disease transmission, migration, wildfires, more intense hurricanes — none of it going to stop magically with this bill. That does not mean that every ton of CO2 that we avoid putting into the atmosphere doesn’t reduce the risk of climate chaos. It absolutely does. It just means that there is a very long road ahead.

So let’s not wonder if this bill is ambitious enough to stave off the climate crisis. It is not. The climate crisis is not like a broken leg, where you find a good doctor and he puts you in a cast for six weeks and you’re back to normal. There is no “fix” for the climate crisis. There is no going back to “normal.” There is only a long, hard fight for a better world. The passage of IRA is a big win. The activists and policy wonks who shaped it and fought for it deserve a place on whatever the climate equivalent of Mt. Rushmore turns out to be.

But the fight continues.

What’s next? Hard choices on deeper, faster CO2 cuts. Hard choices on who gets to live behind a sea wall and who doesn’t. Hard choices on how rich people can compensate poor, vulnerable people for their losses. Hard choices on how avert famines. Hard choices on how to ensure clean drinking water on a planet with nearly eight billion people. Hard choices on how to stop the rape and pillage of the ocean and the decline of coral reefs. Hard choices about how to protect the millions of people who are fleeing from parts of the world that are too hot or too wet to live in. And perhaps most of all, hard choices on how to beat down the fossil fuel thugs and keep democracy alive during all this climate chaos.

In the end, the only metric that really matters is up in the sky above Mauna Loa. I want to believe we have hit an inflection point and this is the moment when the Keeling Curve starts to fall and it becomes clear that we took dramatic action to save ourselves and the world we live in. But it will be a while before anyone can say for sure.

Best of Rolling Stone